Two hundred years after the Sherman Anti-trust Act brought about the fall of Rockefeller’s monopoly control, Bernie Saunders and Elizabeth Warren pushed for America to once again decide whether Pepsi (PEP.NASDAQ), Nestle (NESN.SWX) and Amazon (AMZN.NASDAQ) are agreeable corporate spouses or abusive partners slipping in after a trial separation, but in the age of post-modern capitalism are they just promoting ineffective black-and-white partisan politics in a complex world of grays?

Two hundred years after the Sherman Anti-trust Act brought about the fall of Rockefeller’s monopoly control, Bernie Saunders and Elizabeth Warren pushed for America to once again decide whether Pepsi (PEP.NASDAQ), Nestle (NESN.SWX) and Amazon (AMZN.NASDAQ) are agreeable corporate spouses or abusive partners slipping in after a trial separation, but in the age of post-modern capitalism are they just promoting ineffective black-and-white partisan politics in a complex world of grays?

As the Golden Age of Capitalism ended and stagflation broke down Neo-Keynesian economic paradigms in the 70s, Ayn Rand’s individualism stepped into the spotlight and Friedman’s idea of free market economy mended America’s relationship with monopoly, instigating the largest wave of corporate consolidation since the days of U.S. Steel.

Today, just three companies in the United States control about 80% of mobile telecoms, another three supply 95% of credit cards and only four airlines make up 70% of flights.

If Friedman had managed to tack another 15 years to his life, he’d be wearing a grin. In his mind, monopolistic competition meant freedom and self-determination was paramount to the oft-maligned American economist:

If Friedman had managed to tack another 15 years to his life, he’d be wearing a grin. In his mind, monopolistic competition meant freedom and self-determination was paramount to the oft-maligned American economist:

“A society that puts equality before freedom will get neither. A society that puts freedom before equality will get a high degree of both.”

Friedman’s world was one of efficiency, directed to satisfy the consumer above all else. Large firms could produce more for less, ship further and employ more.

Mega-business movers grew new markets from scratch much quicker and better than a bickering army of perfect competition, how else would railroads have crossed America without the corresponding consolidation? So, is monopoly control necessary?

For the sake of argument, let’s examine Amazon and its capture of ecommerce to see how Bezos’ version of monopoly control has impacted both business and culture.

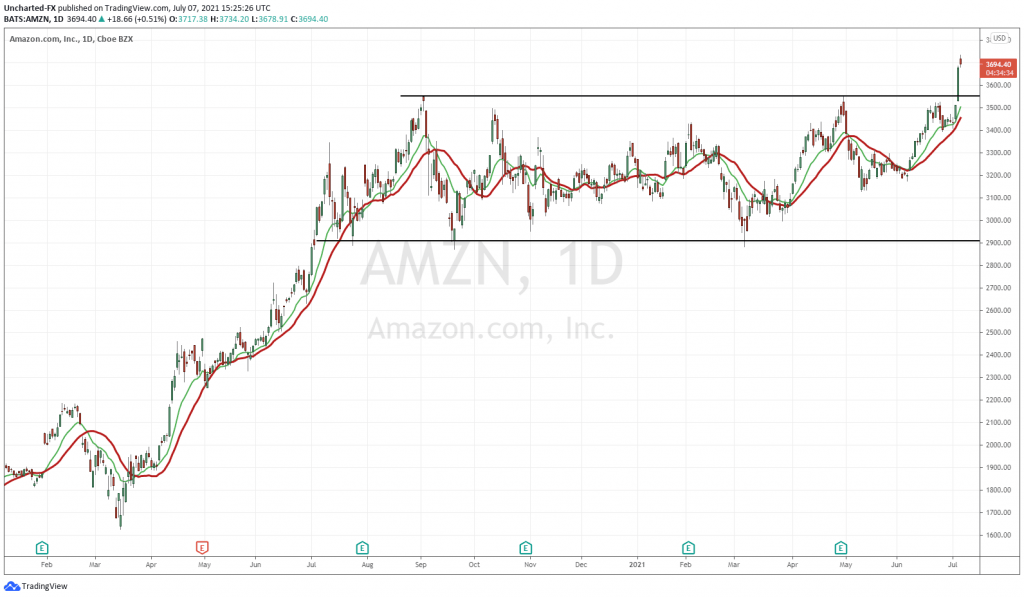

Amazon is touted as a leader in technology and retail distribution, but the company isn’t just a sales platform for 3rd party vendors, it has over 80 private label product lines of its own (Amazon Retail), from apparel and accessories to food and beverage, making it a major consumer product manufacturer as well.

On top of controlling 37.7% of American ecommerce, the enigmatic company has grown beyond retail, with web services (AWS), financial services (merchant cash advances), healthcare (Amazon Care), gaming (Amazon Game Studios) and entertainment (Amazon Studios, Prime Video, Amazon Music Unlimited).

So how did Bezos do it?

The Amazon Way

From the start, Bezos took Amazon into a different direction, he didn’t just want to pay lip service to customer satisfaction, he wanted the whole focus to be on the consumer.

From the start, Bezos took Amazon into a different direction, he didn’t just want to pay lip service to customer satisfaction, he wanted the whole focus to be on the consumer.

Thus, Amazon was built facing out both in software development and service philosophy. Bezos vowed to grow aggressively using a management methodology that some critics contend breeds toxicity in the workplace.

Bezos chose books because they were easy to ship, hard to break and customers always knew what they were getting. Amazon would then use the data it gleaned from selling books to determine what else affluent customers would buy.

However, Bezos knew that to gain any sort of traction, he would have to dominate the space he entered – gain monopoly control. Not only were books easy to ship, the sector was fragile and living on precarious margins.

There was an important shift in bookselling during the 90s. Publishers were bowled over by big box bookstores like Barnes and Noble and failed to set off-price discounting policies. Books suddenly became subject to economies of scale.

Amazon took the discount baton and ran with it further than anyone to date. Critics claim Bezos began selling books below Amazon’s effective operating cost. According to a recent article in Publishers Weekly, that policy hasn’t changed, the online retailer was still selling titles at a 55% discount during the 2017 holiday season.

Since Amazon opened its doors in 1995, the company has grown astronomically, selling 807 million physical books and 560 million e-books in 2018 alone. The online “everything” seller now controls 42% of the global physical book market and 89% of the global e-book market.

This puts indie bookstores in an untenable situation. Indie booksellers typically operate on a tiny margin of 4% or less. As such, they require a minimum 50% discount from their publisher to survive. Currently, indie bookstores are only given 43%-47% discounts from their publishers for trade titles, doesn’t bode well for sustainability.

This is doubly painful when you consider big booksellers like Barnes and Noble are clinging to life and indie booksellers are the last true guardians of the printed word.

In the face of all this, Bezos remains glib about Amazon’s impact on booksellers, publishers and authors, as his infamous statement to Charlie Rose attests:

“Amazon is not happening to bookselling. The future is happening to bookselling.”

The “future” happening to bookselling sits on the tip of Amazon’s corporate spear. However, taking Amazon behind the barn to put a bullet in its head does little to solve the problem plaguing big business today – skin in the game.

Nassim Nicolas Taleb’s book of the same name discusses a concept enshrined in the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi almost 4,000 years ago – symmetric risk in all transactions. Basically, this means if I am a banker and I make a bad investment decision, I go down with the ship instead of turning to the government or taxpayers for a handout.

Nassim Nicolas Taleb’s book of the same name discusses a concept enshrined in the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi almost 4,000 years ago – symmetric risk in all transactions. Basically, this means if I am a banker and I make a bad investment decision, I go down with the ship instead of turning to the government or taxpayers for a handout.

Like the banking executives who hid risk deep inside their financial instruments leading up to the 2009 crisis, companies like Amazon hide their risk in the continual issuance of corporate bonds. For instance, a bookseller’s risk for selling books below cost is bankruptcy, but if that bookseller is shielded by billions in corporate debt financing, the risk is suddenly transferred to the competition.

Friedman did espouse freedom, but he also had a caveat so businesses wouldn’t use his phrase as a corporate license to kill:

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

Amazon’s asymmetric risk relationship with its vendors is neither open nor free as illustrated by its recent announcement banning third-party vendors from using Fed Ex’s ground network if they intended to be a part of Amazon’s Prime program – more monopoly control.

Bezos suffers nothing if a vendor chooses not to be strong-armed, as there is a line five miles long of people ready and willing to replace them. The vendor, on the other hand, has no real options, no perfect substitute, not even a good approximation to the ecommerce clout of Amazon.

Vendors aren’t the only ones holding the short end of Amazon’s stick, the company’s discount recoupment program focuses solely on suppliers, squeezing them for every dime they have with surprise https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistration costs and storage fees.

With a $943 billion market cap and $27.7 billion in debt financing, Amazon can easily afford the attrition necessary to squash competition and subjugate suppliers – all without the commensurate risk.

With a $943 billion market cap and $27.7 billion in debt financing, Amazon can easily afford the attrition necessary to squash competition and subjugate suppliers – all without the commensurate risk.

There is asymmetric risk within the company as well as illustrated by the two-tier existence of Amazon employees. On the one hand, you have managers, coders, etc. and on the other, you have the warehouse floor staff.

Bezos is quick to celebrate his white collar contingent, paying healthy salaries and big benefits for those that survive. In this, he has transferred the risk of losing brain power to his warehouse workers who endure at Amazon with minimum wages and little or no benefits.

To further illustrate this disparity of risk, even if a programmer is let go from Amazon, they can wear their employment like a badge of honor during their next interview, but if a warehouse worker is let go, they have to explain why they can’t hold down a simple job.

Even if Amazon has hid the true extent of discounts and returns between gross and net sales, and through restrictive practices, has commandeered the ecommerce market, lopping the head off the snake may do more harm than good. So how do we deal with anti-competitive practices and keep our social fabric intact?

The Right Way?

Government oversight has been the go-to for many social activists seeking justice in the corporate community when monopoly control rears its ugly head, but this can be more detrimental than the problem itself.

Government oversight has been the go-to for many social activists seeking justice in the corporate community when monopoly control rears its ugly head, but this can be more detrimental than the problem itself.

Overregulation not only stifles development and hurts profits, the resulting regulatory recapture may just cancel out any good the regulation was meant to create. Also, if the rules reach draconian levels, corporations will just pull up stakes and go somewhere where they won’t get hassled.

Regulation isn’t completely bad, however. In thoughtful moderation, it can raise the barrier against potentially adverse future events, forcing companies to keep skin in the game. So how can we make this work?

Sales tax

Amazon created an empire utilizing tax avoidance on both state and federal levels. More specifically, the company refuses to collect sales tax from 3rd party vendors which make up over half of the website’s business.

Amazon created an empire utilizing tax avoidance on both state and federal levels. More specifically, the company refuses to collect sales tax from 3rd party vendors which make up over half of the website’s business.

States can’t reliably collect this tax from vendors directly as vendors are either unaware of their responsibility or they have taken a page out of Amazon’s playbook. According to a report by researchers at The Capital Forum, California loses $431 million in state sales tax each year to errant 3rd party Amazonians.

Unfortunately, Amazon doesn’t care, not only does it profit from every transaction made, tax or no, this travesty gives the company another unfair price advantage over online competitors and legitimate brick-and-mortar businesses.

In order to offset this wildly divergent risk asymmetry, states could set a ceiling on non-taxable sales transactions and once they cross that line, the financial agent (Amazon) would be responsible for collecting and remitting said sales tax. Amazon already has all the services in place to make this happen. After all, it has monopoly control.

Corporate tax

In 1996, Bezos pulled up his Washington State roots and re-incorporated in Delaware because Washington charges 1.5% business and occupancy tax on gross receipts and Delaware bills 8.7% on federal taxable income related to business done within the state. This creates over 74% in state tax reductions.

Before you start lobbing rotten fruit at Bezos, corporations are bound by law to care for the financial well-being of their shareholders. So, when an opportunity comes up that will cut costs and add to shareholder value, management must take it. Or do they?

A company’s obligations to the financial well-being of their shareholder really depends on the whims of the shareholder as to what constitutes value. Amazon was able to convince their shareholders that negative cash flow and mountains of debt financing signaled value in the long run, even though you couldn’t see it on the company’s bloody bottom line.

A company’s obligations to the financial well-being of their shareholder really depends on the whims of the shareholder as to what constitutes value. Amazon was able to convince their shareholders that negative cash flow and mountains of debt financing signaled value in the long run, even though you couldn’t see it on the company’s bloody bottom line.

With all his charm, could Bezos just as easily have sold his shareholders a greater vision of value growth as it applied to the commonwealth surrounding Amazon’s operations in the states where it did most of its business? In short, probably not because there are no Friedman-approved incentives to really deal with monopoly control.

So in lieu of that, maybe state and federal taxation bodies should tax companies, not where they are incorporated, but in the jurisdictions where they make their money. This might prevent untaxed value from slipping out of the state and support local social initiatives, which in turn creates business and jobs.

Of course, this kind of tax reform would require a unified front among states, something we haven’t been able to accomplish yet. And, as Andrew Mellon pointed out in 1924:

“The history of taxation shows that taxes which are inherently excessive are not paid. The high rates inevitably put pressure upon the taxpayer to withdraw his capital from productive business.”

Share-based compensation

As discussed in one of my previous articles, share-based compensation ironically grew out of legislation meant to curb outrageous CEO salaries. In the end, the salaries continued to skyrocket, but now CEOs could defer their income tax for years while still using their paper as collateral for cash loans.

Meanwhile, wage employees pay tax on every dime they take home, and typically have no share-based compensation to offset the loss. This creates a tremendous asymmetry between board directors, management and employees with employees shouldering much of the operational risk.

For instance, the board of Regions Financial paid themselves handsomely with phantom shares in a year when the company had to run-off $6.4 billion in bad loans. Did the rank and file benefit as well or did they absorb the cost of the board’s greed along with shareholders?

Maybe put a cap on share-based compensation as well as a limit how much a CEO can be paid compared to their average employee. This might help to eliminate risk asymmetry within the company.

Corporate veils

One of the reasons for incorporating, is that it removes the owner’s personal liability when it comes to corporation. This is a corporate veil. Corporate veils also separate liability between subsidiaries and their parent companies. At first blush, this makes complete sense because of potential complexity of corporate operations.

One of the reasons for incorporating, is that it removes the owner’s personal liability when it comes to corporation. This is a corporate veil. Corporate veils also separate liability between subsidiaries and their parent companies. At first blush, this makes complete sense because of potential complexity of corporate operations.

As John Malkovich described British Petroleum in Deepwater Horizon (2016), multinationals are made up millions of moving parts, thousands upon thousands of people, each doing their job contributing to the whole.

With all this activity, how is a CEO of an American company expected to keep tabs on a South African subsidiary? Well, each subsidiary may work independently, but it’s the independence of a 12-year-old boy – any competent parent will have a good idea of what their child is doing and, in most cases, will have given them permission to do so.

As such, Canadian courts are leading the way when it comes to breaking down corporate veil protections. Piercing the veil or removing it entirely will make CEOs accountable all the way down and less likely to allow subsidiaries to commit prosecutable offenses.

However, even though this would greatly increase skin in the game, it leaves room for abuse and if executives and board directors are made liable for the corporation without any protection, we may see a decline in new business development, a disruption in world trade and a moratorium on public works projects.

You gotta have soul

According to Taleb, putting skin in the game remains somewhat superficial until a CEO/company is willing to put their soul in the game. As explained in his book, having soul in the game means you have skin in another’s game and are willing to sacrifice for the sake of the collective.

Soul in the game, also known as welfare capitalism, created, among many other things, Hershey, Pennsylvania, workers health insurance, 8-hour workdays and paid vacations.

Soul in the game, also known as welfare capitalism, created, among many other things, Hershey, Pennsylvania, workers health insurance, 8-hour workdays and paid vacations.

So, if companies like Amazon continue to use their monopoly control to maneuver around paying taxes, perhaps they can be convinced to provide a public good instead. For instance, in return for certain financial considerations, Amazon must now follow through on Bezos’ bullshit promise to house two copies of every book ever printed. By the way, Jeff, whatever happened to the Alexandria project, did you lose it in the divorce?

Joking aside, I will not pretend to have the answer. Smarter people than I have tried to tackle the problem of post-modern monopolies, but all bets are off in this world of negative interest rates. Unfortunately, monopolies and negative cashflow companies are probably here to stay, so instead of screaming for blood, maybe we should just ensure they have skin in the game.

–Gaalen Engen