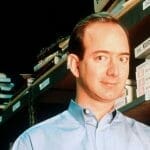

Jeff Bezos started Amazon in his garage with a couple hundred grand from his parents. This ex-hedge fund manager turned internet titan and evil king-making gnome has often been lauded for his customer-focused business strategies, aggressive business development and industry prowess, but how challenging is the journey when you’re a 1500lb gorilla on someone else’s dime?

Jeff Bezos started Amazon in his garage with a couple hundred grand from his parents. This ex-hedge fund manager turned internet titan and evil king-making gnome has often been lauded for his customer-focused business strategies, aggressive business development and industry prowess, but how challenging is the journey when you’re a 1500lb gorilla on someone else’s dime?

Let’s make a comparison between Amazon and Sears. Sears is a sad story now, but in its day at the turn of the century, it did what Amazon did today with none of the tax breaks or massive debt Bezos needed to make his dream come true. And if its leadership hadn’t missed the boat, it could have easily squashed Amazon long before the e-commerce leviathan had the chance to eviscerate the bookseller industry.

Amazon v.s. Sears – The early years

The iconic mail-order company started out in the late 1800s when Richard Sears bought some unwanted watches from a jeweler and started the R.W. Sears Watch Company in Minneapolis. Sears had made good money hawking watches and jewelry, but Rural Free Delivery, like the internet for Bezos, was the tool that turned the niche luxury item distributor into the commercial powerhouse Sears, Roebuck and Company.

The iconic mail-order company started out in the late 1800s when Richard Sears bought some unwanted watches from a jeweler and started the R.W. Sears Watch Company in Minneapolis. Sears had made good money hawking watches and jewelry, but Rural Free Delivery, like the internet for Bezos, was the tool that turned the niche luxury item distributor into the commercial powerhouse Sears, Roebuck and Company.

When Goldman Sachs led Sears to the public market in 1906, it was big news. As the first major retail offering in the United States, it raised roughly $1.14 billion in 2019 dollars. The transaction signaled an economic turn from manufacturing to consumerism in America and Sears was leading the movement. Amazon, on the other hand, raised $86.58 million when it debuted on market in 1997. Sears seems certainly stronger out of the gate.

At that point, Sears already had yearly revenues of $1.09 billion in 2019 currency. Amazon, on the other hand, came to the market in 1997 with only $25.25 million in revenues and a $9.2 million net loss in today’s dollars.

Seven years after going public Amazon finally had a profitable year in 2004, seven years after going public, with a net revenue of $5.26 billion and a net profit of $35 million. In their seven years after going public, Sears announced $2.21 billion in revenues in 2004 dollars. Sure, that may be less than half of what Amazon brought in, but Sears managed to pull $252.2 million net profit, which is over seven times what Amazon was able to extract.

Jeff Bezos is lauded for his prime directive of “getting big now” and his obsession with logistical efficiency, but just how sustainable are his strategies? Are they just a managerial pyramid scheme propped up by massive amounts of debt or is there steak behind all that sizzle?

As attested to in its 1940 Annual Report, Sears maintained strong mutually beneficial relationships with its customers, its employees and its suppliers. The report praised the company for its professional relationships lasting decades, ample employee bonuses and profit-sharing fund that made employees the largest singe stockholder in the company. And to boot, it paid dividends.

In Amazon’s inaugural 1997 letter to shareholders, Bezos laid out a business philosophy focused on the long term regardless of Wall Street’s reactions. He was going to cut anything that didn’t make reasonable returns and boldly invest in every venture to gain market leadership advantages. Amazon also promised to never pay dividends in favor of reinvestment in the company.

Two giants in their prime

In 2018, Amazon totaled $232.89 billion in annual net sales and brought home $10.07 billion in net income. That’s a 4% return. Sears reported its fiscal 1940 revenue as $17.23 billion in 2018 dollars. On the surface, it looks like Sears pales in comparison to Amazon’s forward-thinking technical might – and if you were talking about sheer growth, you would be correct. Oddly enough however, Sears reported the net income equivalent of $1.04 billion in 2018 dollars. I did the math for you – that’s a 6% return.

Operationally, it seems Sears was more efficient in realized profit from revenue even though their fulfillment methodologies were ‘antiquated’ and its business development was ‘hampered’ by organic progress. But there’s something else to consider.

Sears announced it had $6.58 million in notes payable in 1940 with only $814,500 payable the year before. Debt made up 1.1% of net sales, a number that wasn’t even a point of serious consideration in fiscal 1939. Amazon’s debt in 2018 amounted to $25.0 billion. That’s 11% of net sales and Amazon has AWS as an extra revenue generator.

The responsibilities of success

Based on its model of welfare capitalism, Sears executives believed investment in commonwealth returned to the company in terms of revenues, labor retention and inventory quality.

Robert E. Wood, ex-brigadier general and chairman of Sears’ board, laid out the vital intangibles he felt gave the company’s balance sheet its value. It was all about harmonizing the five necessary relationships between Sears and their:

- Customers

- Employees

- Stockholders

- Manufacturing sources (suppliers), and

- The public

Customers and employees

Sears’ relationship with its customers was evident in its sales numbers in fiscal 1940, which were its highest to date and projected to climb. As an investment in customer experience, the company employed 57,029 regular staff and 15,317 extra part-time retail staff for holiday rushes for a total payroll of $96.09 million in fiscal 1940 or $1.76 billion today. Sears was proud to state that it had kept tabs on regional employment and Sears staff consistently earned more than their sector counterparts.

Amazon employed approximately 647,500 full-time and part-time workers in 2018, but according to a proxy statement released in April 2018, the median employee other than Jeff Bezos was paid $28,446 in 2017. The poverty threshold for an American four-person household in 48 states and DC was $24,600 in 2017. That means Amazon, at the top of its game, gives its employees a 13% buffer against poverty.

Sears is harder to determine because their records aren’t specific but let’s say of the 15,317 non-regular workers, half are part time and half are seasonal. For the sake of argument, let’s now say seasonal retail workers work maybe three months out of the year and part timers work for six months. If payroll was a total of $96.09 million divide it equally among all in 1940 part-time and seasonal retail staff, you have $1,328.20 per worker.

If seasonal workers only worked a quarter of the year, each of those workers would have been paid $1,328.20 divided by four or $332.00. Using that thinking, each part time worker earned $1,326.2 divided by two or $663.10. That means total part time workers and total seasonal workers earned a combined total of $7.62 million, leaving each regular worker with $1,640 annually. According to the 1939 U.S. Census, poverty threshold for workers outside of mining and manufacturing was $1,281. It looks like Sears gave their regular employees a 22% buffer.

If seasonal workers only worked a quarter of the year, each of those workers would have been paid $1,328.20 divided by four or $332.00. Using that thinking, each part time worker earned $1,326.2 divided by two or $663.10. That means total part time workers and total seasonal workers earned a combined total of $7.62 million, leaving each regular worker with $1,640 annually. According to the 1939 U.S. Census, poverty threshold for workers outside of mining and manufacturing was $1,281. It looks like Sears gave their regular employees a 22% buffer.

In terms of profit-sharing, Sears contributed $3.01 million to its profit-sharing fund in fiscal 1940 and the employees’ pension fund owned 11% of the company’s 5,643,501 issued and outstanding shares, making it the business’ largest single investor.

In stark contrast, Amazon announced it would phase out its employee restricted stock unit program in October 2018 after announcing a $15 minimum wage for its hourly fulfillment workers. Amazon also moved to eliminate bonuses and other forms of incentives, saying the wage increase would provide stability. The same policy apparently doesn’t apply to Jeff Bezos, who with ~78.88 million shares of Amazon’s 494.66 million issued and outstanding shares, is the company’s largest shareholder with 16% control. On paper alone, Bezos is worth $140.04 billion while his employees remain voiceless and live three steps from the edge.

In 1940, Sears had 7,000 manufacturing sources; 150 of which had been selling their product to the company for over 30 years, 350 between 25 and 30 years; 110 between 15 and 25 years; 2000 between 10 and 15 years. Wood was quick to exclaim, “Such relationships surely could not exist over such periods of time except on the basis of mutual respect and mutual satisfaction.”

Suppliers

Amazon, on the other hand, has a love/hate relationship with its third-party vendors. Vendors have to contend with being banned over negative reviews and getting stuck with hundreds of thousands in merchandise or having six-figure sales accounts frozen for months. If Amazon’s bots determine your price is too high compared to the competition, it could remove your buy button even if people are still buying your product, forcibly killing your sales. Or Amazon could force you to go through Vendor Central where you sell to them at wholesale and have no power over pricing or marketing. Amazon is slowly turning from an e-commerce cash cow to a necessary evil that manufacturers drag their feet to partner with.

Amazon, on the other hand, has a love/hate relationship with its third-party vendors. Vendors have to contend with being banned over negative reviews and getting stuck with hundreds of thousands in merchandise or having six-figure sales accounts frozen for months. If Amazon’s bots determine your price is too high compared to the competition, it could remove your buy button even if people are still buying your product, forcibly killing your sales. Or Amazon could force you to go through Vendor Central where you sell to them at wholesale and have no power over pricing or marketing. Amazon is slowly turning from an e-commerce cash cow to a necessary evil that manufacturers drag their feet to partner with.

Wood also had this to say about Sears’ commitment to the public, “Sears, Roebuck and Co. freely recognizes that you cannot have rights without responsibilities, or privileges without obligations. It recognizes that the rights and privileges of doing business in any community entail self-imposed responsibilities and obligations to that community. These responsibilities and obligations extend beyond the letter of the contract; there is no slide-rule formula for the determination of their limits. They lie within the definition of good and decent citizenship.”

Sear made a concerted effort to be what could be called a good corporate citizen, doing charitable acts such as sending kids from 25 states to agriculture college, and providing livestock to farm boys and girls in rural communities while paying $18.82 million in federal, state and local taxes – 33.6% of its gross sales.

Commitment to community

Amazon, with its global reach, is held to an even higher standard which it falls wildly short of. It claims to have donated $100 million to charity through its AmazonSmile program – that’s 0.06% of the company’s revenue in 2018 and 1.4% of its 2018 net income. Meanwhile Amazon only paid $756 million in state taxes because it appears the federal government paid $129 million for the privilege of Amazon’s patronage. So, Amazon’s tax commitment made up 0.3% of its 2018 net sales and 8.0% of its net income. And certainly, corporate compliance differences do NOT account for the two companies’ community contributions.

Sears went on for twenty more successful years before bad management and lack of vision laid fatal body blows to the company, leaving it in bankruptcy. Conversely, Amazon recently experienced its first sales contraction in two years, is under scrutiny for having become a monopoly and is in the game of shaving pennies to improve balance sheet growth. All this on top of staggering debt coming due over the next decade.

In the end Sears had a symbiotic relationship with America, feeding the nation to feed itself; Amazon to be blunt and repetitive, is a slithering lipless parasite. Instead of feeding the market, it feeds on the market and remains impervious to the consequences of under-performance, shielded, as they are, by billions in debt, which if you think sounds ridiculously unsustainable – is. We’ll give him this: Bezos tapped into a new medium and changed the way big business handled software development, but that’s where the added value stops.

In the end Sears had a symbiotic relationship with America, feeding the nation to feed itself; Amazon to be blunt and repetitive, is a slithering lipless parasite. Instead of feeding the market, it feeds on the market and remains impervious to the consequences of under-performance, shielded, as they are, by billions in debt, which if you think sounds ridiculously unsustainable – is. We’ll give him this: Bezos tapped into a new medium and changed the way big business handled software development, but that’s where the added value stops.

Amazon “won” e-commerce and as a result, became a dominant player in cloud computing: but it was only able to do so because it operates as a monopoly, treats its employees as an ever-replaceable, temporary solution to automation and avoids taxes like Trump avoids reading.

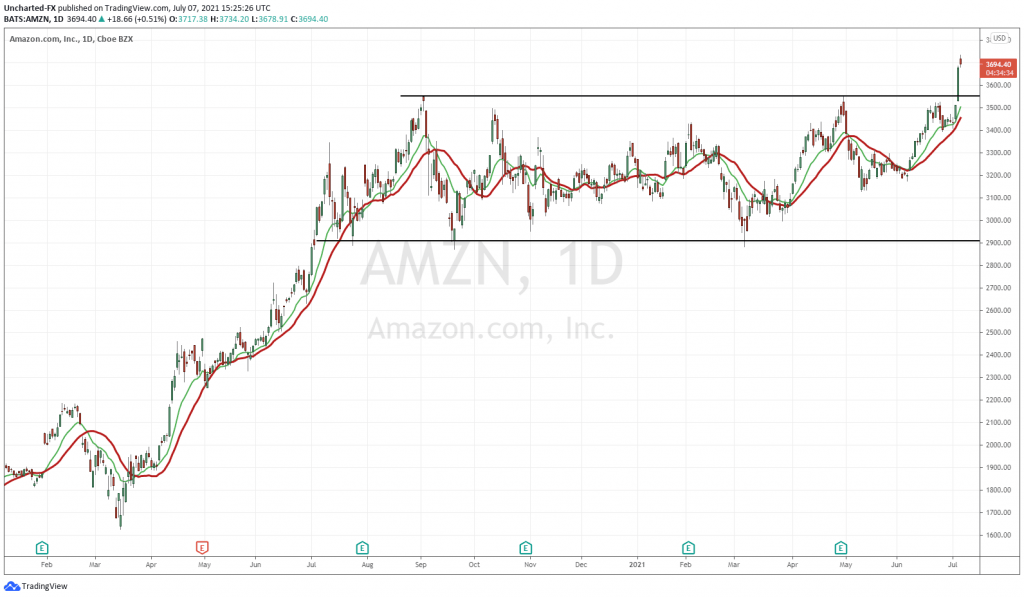

Sure, the company may trade four times to net sales, but it still trades at 23 times earnings, which doesn’t even come close to justifying market cap – its earnings will never grow to the point where it does.

Will this stock valuation normalize over the next 12 months as sales growth plateaus, or will Bezos have to continue to shift gears fast enough with note-powered seat-of-your-pants inorganic growth to keep investors from questioning mountains of debt and a growing logistical bottleneck?

Let’s look at the past for any comparable examples:

Sears’ success took time but delivered real value until the company went into finance in the 80s and like GE, learned you can’t do everything. The arrogance of Sears Tower with the company’s lofty predictions of one day filling all 110 floors with Sears employees, sunk the company’s reputation and publicly announced the company’s heartbreaking departure from its humble beginnings into a shameful death spiral, loaded with debt and burdened with a billion-dollar vanity project.

Sears’ disastrous end is exactly how Amazon is starting its journey, loaded with debt and currently working on HQ2 and we have no blueprint moving forward of how they could possibly dig their way out of their hole.

When all is said and done, which method is better?

As an investor, 1940 Sears presents a growth story in line with the company’s actual performance. It may not have been a ten-bagger, but it gave a reliable return with dividends. Amazon presents potential but much greater risk as the company grows at a blinding rate in a debt-shielded vacuum – and lord knows, America eats potential and spits it back out, drained, depressed and anxiety-ridden to the point of stagnancy.

Amazon’s remedy of throwing money at a problem, like the 300% increase in shipping costs from 2017 to 2018 doesn’t fix things – just ask Donald Trump Jr. Once the banks turn off the money supply, nothing will be able to hide the fundamental rot and foundation of sand.

Sears’ welfare capitalism only truly succeeds if the world around it does, creating sustainable wealth on Wall Street and Main Street. It gives a feeling that we succeed together. Amazon is more at ease with growing in spite of the world around it – true value be damned. If Amazon’s philosophy is allowed to continue, we may end up drowning in negative interest rates.

Sears’ welfare capitalism only truly succeeds if the world around it does, creating sustainable wealth on Wall Street and Main Street. It gives a feeling that we succeed together. Amazon is more at ease with growing in spite of the world around it – true value be damned. If Amazon’s philosophy is allowed to continue, we may end up drowning in negative interest rates.

Welfare capitalism fosters a model based on fundamentals and in the case of Amazon versus Sears, it seems to be more efficient, with many entourage benefits. Even with Robert E. Wood’s problematic America First agenda and his centralized control of operations, I would still pick his venture over the nihilistic pseudo-value of corporate welfare.

Welfare capitalism fosters a model based on fundamentals and in the case of Amazon versus Sears, it seems to be more efficient, with many entourage benefits. Even with Robert E. Wood’s problematic America First agenda and his centralized control of operations, I would still pick his venture over the nihilistic pseudo-value of corporate welfare.

Bezos, its been a slice, but you’ve had most of the cake, its time somebody broke up your party.

–Gaalen Engen