A translation of this article is available in Chinese at our partner website, NAI500 here.

Before I get into the U.S. Fed and its market liquidity shenanigans, I should explain something that changed the way I view the world, kinda like the time I discovered Disney shoved lemmings off a cliff for ratings, almost making a manufactured myth science, so here goes:

It might surprise you to know that no matter what your economics professor told you, there was never any barter system, we have been operating on credit and collecting debt since Ugh discovered how to harness the power of fire.

It might surprise you to know that no matter what your economics professor told you, there was never any barter system, we have been operating on credit and collecting debt since Ugh discovered how to harness the power of fire.

It might also surprise you that money has no value and is merely a measuring device to compare worth of disparate objects. If anything, money is an IOU on an age-old debt that most of us have forgotten about.

For instance, when the Bank of England opened its doors in 1694, it was based on providing a £1.2 million loan to William III to rebuild the country’s navy after a disastrous defeat to the French at the Battle of Beachy Head.

The bank then issued notes or IOUs on that debt. Those notes were traded and used as currency by the public – all with the idea that the government would eventually pay back that money. Therefore, those notes represented the silver William used for the upkeep of England’s navy and had no inherent value.

To my knowledge, that debt was never repaid because if it had, England’s currency would be worthless. Debt and credit are as integral to the human experience as speech and even though the whole system is routinely vilified in the media, it is absolutely necessary.

And since life itself is a debt only paid by our passing – it is inescapable. However, when debt wildly outstrips underlying assets or the ability of the issuer to pay, it pulls a peg out of our three-legged banking system and leaves it without the foundation is was built on.

These socially skint moments typically result in recession and in more extreme cases market crashes like the Tulip financial crisis in 1637. People bought tulips like there was no tomorrow using highly leveraged margin contracts to snap up assets they couldn’t possibly afford – a tulip at the time cost the same as a mansion. When the world gave its collective head a shake and refused to pay the ridiculously inflated price attributed to tulips in 1638, values plummeted, and some investors lost the shirt off their backs.

The Tulip Crisis is a hotly debated topic. Some historians state it wasn’t as widespread as many believed and was blown out of proportion to produce a morality play on the sins of greed and speculation. Regardless of its size or impact, the Tulip Bubble illustrates what can happen when debt overpowers value in the markets.

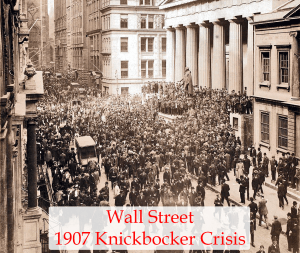

From that day forward, we have been plagued with numerous bubbles/crashes from the Knickerbocker Crisis of 1907 to the most recent 2009 financial crisis when mortgage-backed securities crashed, taking the global banking system with it.

From that day forward, we have been plagued with numerous bubbles/crashes from the Knickerbocker Crisis of 1907 to the most recent 2009 financial crisis when mortgage-backed securities crashed, taking the global banking system with it.

In order to mitigate the inherent economic chaos of capitalism in the hands of humanity, the U.S. government created the Federal Reserve in 1913. Since then, an independent board of directors in 12 banking districts determine national monetary policy by controlling interest rates and cash flow.

Even though the Fed wasn’t able to stop either the Great Depression or Lehman Brothers’ criminal pursuit of profit at the turn of the millennia, it claimed its quantitative easing (QE) prevented 2009 from turning into a depression not known since the Dirty Thirties.

After the 2007 financial crisis, American banks, too big to fail, put their fat grubbing hands in our collective pocket and clawed out $700 billion which went toward share buybacks and executive bonuses.

In order to pull the rest of us out of the toilet, the Fed started printing cash and injecting it into the system to dilute market toxicity. They hoped to stimulate spending and job creation by buying up all the bad assets (mostly mortgage-backed securities) that the banks wouldn’t go near.

This would put more money in the system and increase the value of bank-held assets. This shadow capitalization along with lower overnight interest rates made capital easier to borrow, the economy would soon be on its way to victory. Well, it worked…sort of.

The $4.0 trillion-dollar experiment ended in 2014 and was declared a success. The Fed began unwinding its assets slowly so the economy could return to a material footing, but something happened the Fed wasn’t counting on. The money it pumped into the banks never made it to Main Street. Financial institutions like Goldman Sachs instead dumped more money into the financial markets because assets had a far better return than federal interest rates.

The everything bubble

In October, the Fed announced a six-month program to artificially prop up financial reserves of member banks. It planned to snap up $60 billion worth of treasury bills each month – that’s over 300 million of liquidity injection every night. Then, the very next day, in an unrelated move, the New York Fed dropped $104.15 billion to bring liquidity to the financial markets.

In October, the Fed announced a six-month program to artificially prop up financial reserves of member banks. It planned to snap up $60 billion worth of treasury bills each month – that’s over 300 million of liquidity injection every night. Then, the very next day, in an unrelated move, the New York Fed dropped $104.15 billion to bring liquidity to the financial markets.

The Fed managed to unload almost a trillion in assets as it wound down its portfolio after 2014, but this nightly multi-million-dollar commitment will push that number well over $4 trillion again by the time six months is up. We’re right back where we started, and it isn’t showing any signs of stopping.

Investment industry icon, Howard Marks, who I would love to meet one day, has thrown up his hands, saying no one, from Jerome Powell down, knows the full extent of what is happening as a result of QE and no one has a clue what to do next in this scary new world of inverted yields and negative rates. Yet, the Fed stays its course.

This dogged persistence is doubly maddening when you consider the Fed’s ham-handed control of the markets doesn’t seem to be what the financial regulatory body was designed for.

According to the 1913 Federal Reserve Act, in Section 2A, its monetary policy objective is as follows:

“The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Open Market Committee shall maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.”

Nowhere in that mandate, does it mention public or private markets, it only talks about the economy. However, on the front page of the organization’s website, it states rather clearly that the Fed is responsible for, among other things:

“Maintaining the stability of the financial system and containing systemic risk that may arise in financial markets.”

Perhaps I am missing something in translation, but has the Fed broadened its reach without the constitutional power to do so?

The U.S. Fed’s Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) was created by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act in 2010. Part of the responsibilities of this council was to:

“To promote market discipline, by eliminating expectations on the part of shareholders, creditors, and counterparties of such companies that the U.S. government will shield them from losses in the event of failure.”

This seems to a case of “do as I say, but not as I do.” So why has the Fed opened its taps again, is it duplicity to fatten bankers’ bottom lines or are they caught between a rock and a hard place because they started something they just can’t stop?

Europe and Japan are leading the charge when it comes to declining interest rates. Back in October, the European Central Bank (ECB) decided to keep deposit rates at -0.5%, the lowest on record, while the Bank of Japan (BOJ) decided to hover at -0.1%.

Europe and Japan are leading the charge when it comes to declining interest rates. Back in October, the European Central Bank (ECB) decided to keep deposit rates at -0.5%, the lowest on record, while the Bank of Japan (BOJ) decided to hover at -0.1%.

To put this into perspective, I grew up in a time that a bank account drew 10% interest compounded, but in the forty years since, it’s dropped to a fraction of that and only if you maintain a sufficient balance in your account. Of course, this sometimes $1000 minimum is typically out of reach for you and me if we intend to live and pay our bills. So, what’s the incentive to save?

Due to this low interest environment, we are all in search of better yields. Since bonds are starting to cost money to hold and bank accounts are heading that way, where are we going to get the yield that puts our head above water and leaves a legacy for our descendants? Risky assets like speculative stocks, options and other derivatives.

One of the arguments that the Fed’s actions do not amount to QE, is there is no corresponding inflation with the increase in money supply. I contend this isn’t true. To explain: when a central bank prints more money and puts it into the system, the relationship between cold hard cash and the availability of product changes. If there is more money than product available, those products increase in price to compensate – inflation.

What the Fed is doing now hasn’t caused the price of a loaf of bread to jump to $20, but as I said before, this overnight losers’ lottery isn’t going to the streets, its buying stocks, ETFs, hedge funds, etc. Like the loaf of bread increasing in price, so have stocks, widening the spread between real value and unreal market caps to dangerous proportions.

This has distorted investment philosophy and investors are buying inexpensive speculative stocks because the market just keeps going up and money is free, but James Montier, author of the acclaimed The Perfect Value Investor and strategist for $67 billion-dollar Boston money manager, GMO, states:

This has distorted investment philosophy and investors are buying inexpensive speculative stocks because the market just keeps going up and money is free, but James Montier, author of the acclaimed The Perfect Value Investor and strategist for $67 billion-dollar Boston money manager, GMO, states:

“There is a simple, although not easy alternative [to forecasting] …. Buy when an asset is cheap and sell when an asset gets expensive… Valuation is the primary determinant of long-term returns, and the closest thing we have to a law of gravity in finance.”

By value, James was referring to the underlying asset, not share price. Therefore, an expensive stock might not have enough underlying value to support its price – Hello Amazon – and a cheap stock may have more underlying value than you’re paying for – hard to find in today’s market. But most investors only examine price as they clamor to get in on the latest pyramid scheme out of Wall Street.

If it’s this bad now, imagine what it will be like when interest rates in the U.S. slip below zero. Banks won’t have depositors to generate their liquidity, seriously inhibiting both investment and lending. Government bonds will start tanking because why would you invest in a negative yield to get less than what you put in unless you thought the whole world was coming to an end and you needed to minimize your losses.

Also, once the government is unable to derive revenue from T-bills, guess who it will come to for cash with increased taxation.

Unfortunately for the Fed, this latest round of not-QE is a slippery slope that cannot be easily undone without destroying value across the board. Since no one has the political will to bite the bullet, we will keep kicking the can down the road until it grows into a 50-gallon drum full of nitroglycerin and when that explodes, taxes will skyrocket and inflation will finally pop to go stratospheric. We are already in for an economic shock equal to the Great Depression, I don’t know why we’re attempting to up the ante. Jerome, are you listening? Oops, maybe not, the Fed just revved up their overnight bailout scheme, it’s going to be $4.6 trillion in toxic handouts by the end of this. Which begs the question, which bank is about to collapse? Somebody’s holding those subprime car loans and their resulting CLOs, remember that’s 21% of all auto loans in the U.S.

I could be wrong, but with the U.S. and China straight up lying to each other over trade, this roller coaster is about to go off the rails.

I could be wrong, but with the U.S. and China straight up lying to each other over trade, this roller coaster is about to go off the rails.

–Gaalen Engen

Chinese version of this post available on NAI500.com via this link.