Elizabeth Warren’s Accountable Capitalism Act (ACA) threatens to level the corporate playing field in America by bringing labor into the boardroom. Understandably, industrial lobbyists have crawled out of the rot of Washington’s woodwork to lambaste the ACA as a useless partisan ploy bent on destroying U.S. entrepreneurial spirit. So, is corporate codetermination cunningly co-committed or just cataclysmically codependent?

First, some history

Germany’s idea of corporate codetermination was first advocated by Catholic theologian, Franz von Baader, just after the turn of the 19th century.

Baader’s intellectual attempt to alleviate pitiful conditions for the average German worker went on to fuel the Spring of Nations or the Year of Revolution in 1848.

However, it wasn’t until Kaiser Wilhelm steered the newly minted Teutonic confederation toward bankruptcy near the near of the first world war, that works councils (Betriebsräte) made a functional appearance.

However, it wasn’t until Kaiser Wilhelm steered the newly minted Teutonic confederation toward bankruptcy near the near of the first world war, that works councils (Betriebsräte) made a functional appearance.

Unfortunately, to smoothly transition from monarchal rule to a republic, Wilhelm’s replacement, Friedrich Ebert foresaw a counter-revolution and brutally crushed the Betriebsräte movement to prevent it. It would be over twenty years and a world war later before works councils once again held sway in the Fatherland.

Post-WWII Germany was 500 million cubic meters of rubble. Millions of Axis Power prisoners had been pressed into forced labor by the Allies. Many industry leaders had supported the war effort, and as a result, a good deal of those were answering questions at Nuremburg along with nearly everyone who served in Hitler’s https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistration. In short, there was no one to hand the keys to.

Not wanting to back down from the precepts of the Morgenthau Plan, but not wanting to ruin an economic power to which they were tied, the Allied Control Council found a compromise to tearing down Germany’s industrial monopoly with the reinstatement of works councils, which the Nazis had suppressed since burning down the Reichstag.

Works councils teamed with union leadership and sat on corporate supervisory boards, helping guide growth while still considering stakeholder impact.

German works councils have been linked to higher wages, increased productivity and employment opportunity. The practice is still legally embedded in the country’s constitution.

How it works

Work councils, in their modern form, are company-elected labor representatives who operate on the local level and participate in national labor negotiations for a 4-year term.

German industrial relations are split between unions and councils. Trade unions collectively bargain at sector or industrial levels with employers’ associations and works councils deal with job regulation at workplace level.

With a tighter management/labor relationship, there is less chance of strike action and better chance of reducing hours across the board without lay-offs.

According to the Works Constitution Act, councils are created to:

- Ensure the efficacy of ordinances, safety regulations, collective agreements and works agreements in favor of the employees,

- Further the betterment of both workplace and staff,

- Promote gender equality and reconciliation of family and work,

- Take justified employee suggestions up with management,

- Promote inclusivity and integrate persons with severe disabilities,

- Prepare and organize youth and trainee delegations,

- Quash ageism, combat racism and xenophobia in the business, and

- Promote health and safety in the workplace.

Critics paint a different picture however, blaming codetermination for lower profitability, decreased R&D and lack of innovation, not to mention the god-awful sin of making it difficult to terminate an employee without severance or reason.

Critics paint a different picture however, blaming codetermination for lower profitability, decreased R&D and lack of innovation, not to mention the god-awful sin of making it difficult to terminate an employee without severance or reason.

Betriebsräte also have limits on their power. They are unable to veto a company’s action; they are only allowed to vote on how that action is taken. If a company wants to close a department or reorganize it, work councils can’t stop it – only help set the method of how that closure or reorganization is done.

Does it work?

There’s not a lot of studies on codetermination in terms of performance benefits. Many of them have been called into question because of errant data collection and analysis methodologies.

Individual studies fail to show reliable findings on the company level but take the research to the national level and statistics start to make sense.

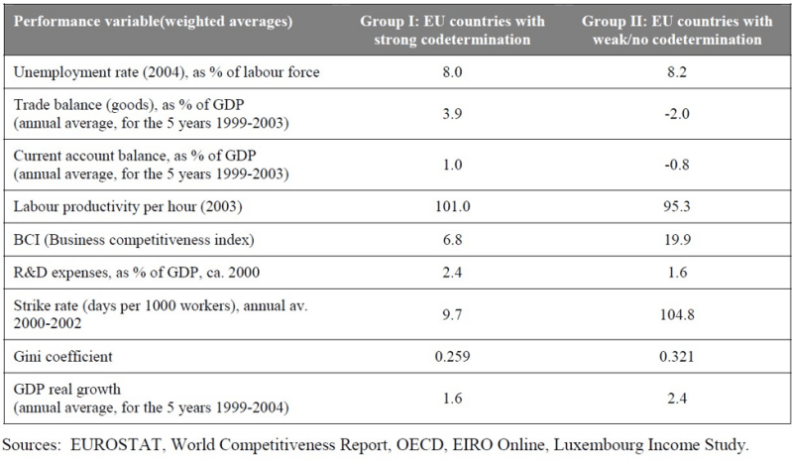

In 2005, Sigurt Vitols published a paper for the European Trade Union Institute where he compared EU countries with strong codetermination and EU countries without, looking for performance differences.

As illustrated by the results, there are notable differences between the two groups with codetermination winning out when it comes to unemployment rates, trade balance, labor productivity, R&D expenditures and strike days.

One of the areas codetermination lost on is GDP, but, as we say time and again @ EG, growing at lightning speed isn’t necessarily a good thing despite what Bezos and Trump might tell you.

Even though codetermination underpinned Germany’s post-war economic miracle, the magic of Germany’s resurgence arose from its reconstruction. From 1951-1961 Germany’s gross national product (GNP) climbed 8% annually – double that of Britain during the same period.

Codetermination was finally codified into Germanic law in the wake of the 1976 oil crisis to soothe tensions between labor and management, but the wild economic growth experienced during the 50s and 60s had waned.

External factors such as the 1989 reunification and geopolitical events like the Mexico Crisis in 1994, the Asian Crisis in 1997 and the global oil price plummet in 1998 buffeted the German economy as much or more than its European counterparts, but according to a Hans Böckler Foundation report filed in October, codetermination served to mitigate the consequences of financial shocks of the 2009 crisis.

External factors such as the 1989 reunification and geopolitical events like the Mexico Crisis in 1994, the Asian Crisis in 1997 and the global oil price plummet in 1998 buffeted the German economy as much or more than its European counterparts, but according to a Hans Böckler Foundation report filed in October, codetermination served to mitigate the consequences of financial shocks of the 2009 crisis.

Conservative-liberal governments in the 80s and 90s combined with rising unemployment along the Rhine caused many in the business community and politics to question the effectiveness of tight regulation in a global free market economy.

Still, in 2017, 90% of West German employees working at firms with more than 500 workers were covered by works councils, but numbers are declining in smaller firms. Much is said about how codetermination has caused companies to relocate out of the country, but there are no reliable facts or sources to verify the extent of these claims.

Codetermination may be ingrained in German culture, but the connection has begun to fester with some business leaders actively avoiding the creation of works councils in their companies.

But would codetermination work in America?

The American labor movement spawned in Boston, Massachusetts when shoemakers and coopers (barrel makers) organized guilds in 1648.

This new ideal of free, negotiated employment continued to gather strength until 1775, when irate citizens seeded the American Revolution by dumping tea in Boston Harbor to protest the royally granted monopoly of the British East India Company.

In 1888, railroad workers enjoyed the first federal labor relations law, entitling them to arbitration and Presidential boards of investigation.

Then, as Anglo-American mariners organized to end their servitude to shipowners under American Admiralty Law and 3,000 black women laundry workers staged one of the most powerful strikes in the history of the south, employers kicked back, taking unions to court for “criminal conspiracies in constraint of trade”.

The ensuing battle was particularly bloody as business owners brought in platoons of Pinkerton agents to violently muscle striking workers. On top of the street-level intimidation, courts were fining unions into bankruptcy and, in the case of Irish labor activist group, the Molly Maguires, hanging their leadership.

After two decades of flying bullets and National Guard interventions, the Clayton Antitrust Act made labor unions legal under federal law and formally granted workers the right to strike and boycott.

Unfortunately, the Taft-Hartley Act, drafted by a Republican congress in 1947, placed severe restrictions on unions, prohibiting employers from hiring only union employees, allowing states to create “right to work” laws and banning secondary boycotts – most of these are still on the books.

When “Operation Dixie” tanked, leaving the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) without any union membership in the South’s massive textile industry, the ballooning growth that was America’s labor movement, popped.

When “Operation Dixie” tanked, leaving the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) without any union membership in the South’s massive textile industry, the ballooning growth that was America’s labor movement, popped.

Globalization in the 70s put American manufacturers on the defensive. With the increased competition, businesses scrambled to save their diminishing margins, mostly by cutting benefits for their workers and quashing any attempts at unionization.

Workers responded with some of the biggest strike actions America has ever known, including the 150,000-strong wildcat (not sanctioned by the union) postal worker strike in 1970.

The bellbottom decade was a radically energetic time for labor organization. According to Lane Windham, author of Knocking on Labor’s Door: Union Organizing in the 1970s and the Roots of a New Economic Divide:

“…there were more union members in the United States in 1979, twenty-one million, than at any other point in the nation’s history.”

Keynesian economics, developed during the Depression, postulated that lower hours and higher wages would create more demand for labor and increase consumption due to more disposable income, but growing globalization and the domestic shift from manufacturing to service industries, forever altered America’s labor landscape beyond Keynesian contexts.

Reagan’s White House was laissez-faire to a fault and made no bones about it. In fact, in 1984, the National Labor Relations Board, created by the 1935 Wagner Act, ruled in favor of employers in 60% of cases decided that year – more than double that of the two previous boards.

Reagan’s White House was laissez-faire to a fault and made no bones about it. In fact, in 1984, the National Labor Relations Board, created by the 1935 Wagner Act, ruled in favor of employers in 60% of cases decided that year – more than double that of the two previous boards.

This partisan governance not only served to erode union organization but also wage growth. In the 34 years between 1979 and 2013, middle-class wages remained stagnant, edging up just 6%. In that same time, low-income laborers lost 5% of their take-home pay. In contrast, high-wage earners saw a 41% increase and the top 1% experienced a 138% bump in pay.

According to Statistische Amter des Bundes und der Lander, the average West German worker brought home 14,117 Euros in 1979. Taking inflation into account, today’s average Teutonic salary is 19% higher than 1979 at 37,084 Euros.

Admittedly, German workers are paying for more in the way of taxes and employment benefits, but even with this tabulated in, they still take the lead with an industrial relations model that American business leaders consider socialist, antiquated and restrictive.

Unlike America where corporations are held in place through legislation and tort law, the German system depends on a series of contracts and mutual agreements signed between the labor market’s holy trinity: trade unions, employer associations and works councils.

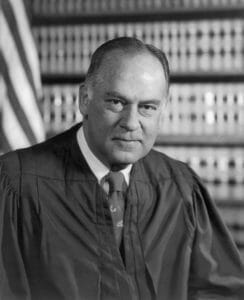

American workers are much more circumspect and are only allowed to negotiate hours and wage rates. This severely limited role was formally justified in a 1981 Supreme Court ruling by Justice Blackmun:

”Congress had no expectation that the elected union representative would become an equal partner in the running of the business enterprise in which the union members are employed.”

This statement flew in the face of another Supreme Court ruling in 1964. Justice Stewart, the presiding judge, established a very different point of view:

“I am fully aware that in this era of automation [1964] and onrushing technological change, no problems in the domestic economy are of greater concern than those involving job security and employment stability….[I]n meeting these problems, Congress may eventually decide to give organized labor or government a far heavier hand in controlling what until now have been considered the prerogatives of private business management.”

Justice Stewart had unwittingly identified a growing trend which was upending America’s shareholder-based capitalism.

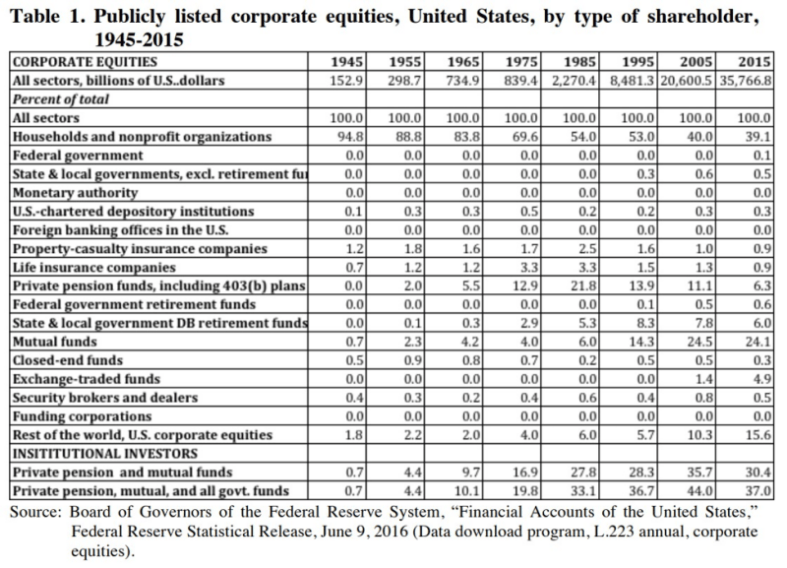

As shown in the table below, public markets in 1945 were far more democratic with 94.8% of publicly traded shares held by households and non-profit organizations compared to 0.7% held by institutional investors like private pensions, mutual funds and government funds.

This majority control ensured a relative alignment between management and employee because there was a good chance that the employee was also a shareholder – shareholder-based capitalism made sense.

However, as legislation loosened up regarding executive compensation and America’s consumerism went into high gear, investment gravitated toward institutions as retail investors dropped off the boards.

So, by 2015, households and non-profits had shrunk their share of the pie to 39.1% while pensions, mutual funds and government funds grew to 37%.

Labour was no longer a shareholder in American corporate business. As a result of this voting void, employees were forced to take a back seat to margins and growth even though they were the means of production.

This detachment is most notably illustrated by America’s federal minimum wage of USD$7.25. The relative poverty threshold in the United States is $11,700. Working eight hours a day for 50 weeks without sick days and holidays, puts a minimum wage worker just $2,800 over the limit.

Since this work schedule isn’t possible both legally and physically, federal minimum wage earners live in relative poverty. Statistics show 80.4 million Americans, out of a population of 327.2 million, worked for minimum wage in 2017.

Admittedly, states have their own minimum wage laws and 29 of them, including DC, exceed the federal requirement. However, all of them have yet to hit the $15 minimum proposed by employment activists and only some of them have ‘promised’ to raise wages to that level years from now.

It would be smart to note that in 2017, the Urban Institute found 61% of non-elderly workers earning 100-200% of the poverty line reported at least one material hardship which made their lives no different than those living below.

The reason for this? Poverty lines are relative and like the core inflation index, it all depends on who you ask. Speaking of which, bozos like Donald Trump are attempting to fudge the numbers further south so all the those struggling to get by, have even less assistance to do it and no sympathy, because officially, they shouldn’t have any problems.

The reason for this? Poverty lines are relative and like the core inflation index, it all depends on who you ask. Speaking of which, bozos like Donald Trump are attempting to fudge the numbers further south so all the those struggling to get by, have even less assistance to do it and no sympathy, because officially, they shouldn’t have any problems.

By contrast, minimum wage in Germany is Euro 1,557 per month or USD$1,715.51 which makes an hourly national minimum wage of $10.72 – over three dollars more than the U.S.

Now, before you start blowing Germany’s horn, its minimum wage puts low income earners just Euro 14.50 over the country’s established poverty threshold. However, according to statistics, one in ten Germans work for minimum wage whereas almost one in four Americans ‘live’ on minimum wage.

So why aren’t we codetermining?

Codetermination makes sense in most cases. It returns focus to stakeholders, more specifically labor, and forces management to consider the best interests of the corporation as a collective rather than using it like a piggy bank for executives and shareholders.

The need for codetermination is clearly illustrated by the American Leisure and Hospitality sector where workers average $16.58 an hour on an average 25.8-hour work week. That’s just $428 per week. It’s no wonder that a recent survey found that only 39% of U.S. households had enough cash to cover $1,000 in emergency expenses.

Neo-liberalism may have freed up the America public markets for debt-fueled inorganic growth and vapor valuations – Hello, Amazon and Tesla – but it hung labor out to dry in exchange for shareholder gain. This is neither equitable nor sustainable.

Works councils have proven themselves not to be solely self-interested, which is a step above C-suite corporate America and their primary shareholders. Working in conjunction with unions and employers, these intermediary representatives decrease voluntary quits, improve working conditions and increase production levels.

One last example: Germany lost on average 11 days of work each year per 1,000 employees by strikes and lock-outs between 1991 and 1999, but only five days per 1,000 employees between 2000 and 2007. These figures for the earlier and later time period compare to 40 and 32 days per 1,000 employees in the United States, 30 and 30 days in the United Kingdom, 73 and 103 days in France, 158 and 93 days in Italy, and 220 and 164 days in Canada (Lesch 2009)[1].

Even with its challenges and short-comings, codetermination seems like a win-win for everyone. In Icahn’s annoying immortal words:

“It’s a no-brainer.”

Still, there probably isn’t much chance codetermination will catch on in the U.S. for some very good reasons.

Works councils and codetermination arose out of certain socially significant scenarios prevalent in post-war Germany. The sting of defeat, the guilt of the upper class and complete collapse of government disempowered the elite to the point where they had to sit down and negotiate with the unwashed masses.

Even with Enron, WorldCom, Walmart and BP, the corporate directorate of America is more powerful than ever and has no compunction to work out a solution.

Futhermore, neo-liberal individualism eschews the idea of banding together in a socialist collective for the betterment of the group and the North American economy is based on that exact set of ideals.

Finally, the U.S. government, led by that lunkheaded thinly coiffed baboon, while admittedly a joke on the world stage, still has enough power at home and has no interest in pissing off corporate donors.

An incoming Warren https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistration might table the idea, but like Jimmy Carter, she’ll get shot out of the saddle before she can do any good.

In the end, codetermination does work, but we are more concerned about getting our packages from Amazon same day than we are about the plight of the working class. Not necessarily a hotbed for revolutionary ideas. Kinda sad.

In the end, codetermination does work, but we are more concerned about getting our packages from Amazon same day than we are about the plight of the working class. Not necessarily a hotbed for revolutionary ideas. Kinda sad.

–Gaalen Engen

[1] Dustmann, Christian, Bernd Fitzenberger, Uta Schönberg, and Alexandra Spitz-Oener. 2014. “From Sick Man of Europe to Economic Superstar: Germany’s Resurgent Economy.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28 (1): 167-88.