We need to talk about cryptocurrency’s carbon problem.

Right now the Bitcoin network alone gobbles up more power than the entire nation of Sweden. That’s a big network. It spits a new block reward of 6.25 bitcoin every ten minutes, each worth approximately $61,568.60 at the time of writing, and Bitcoin is presently down a few thousand bucks from last week.

Tomorrow? Who knows.

What we do know is that as long as Bitcoin mining remains a viable profitable industry, there are going to be companies out there trying to cash in every ten minutes. That means the general trajectory for Bitcoin’s electrical consumption is up rather than down and that spells certain complications depending on how exactly that Bitcoin is mined.

The unfortunate part about this is that many companies use fossil fuels, which only adds to our existing existential climate crisis. You don’t need to be Al Gore to see the effects of anthropogenic climate change—they’re all around us, in the blazing hot summer temperatures and the hurricanes regularly battering the southern coast of the United States.

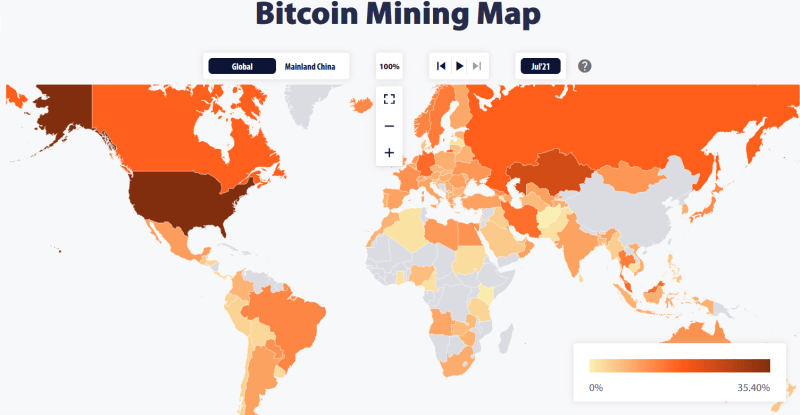

Without a doubt one of the biggest hurdles cryptocurrency is going to have to deal with is environmental in terms of its social and actual impact. The source for information on how much electricity the Bitcoin network gobbles up on a yearly basis is The Cambridge Bitcoin Consumption Index. It will tell you not only how much, but also give you a map indicating who the worst offenders are. Now that China’s removed themselves from the playing field, that leaves the United States as the number one country for bitcoin mining with 35.4% of the average monthly hashrate, followed by Kazakhstan with 18.1%.

The good news is that a good chunk of the United States is powered by sustainable hydroelectric sources, some of which are borrowed from Canadian projects (and sold by Canadian companies and sometimes even by crown corporations). This is a definite improvement on China and their reliance on fossil fuels. But there are some spots in the United States, such as Texas and its antiquated Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), which is still heavily reliant on fossil fuels.

Globally, we use an estimated 103.81 TW of power (with an upper bound of 389.17 TW) to fuel our bitcoin mining escapades yearly, which is more than countries like Argentina and Ukraine use in a year, and about a quarter of what Canadians use.

That’s why we need the Crypto Climate Accord (CCA).

What is the Crypto Climate Accord?

Inspired by the Paris Climate Agreement, the CCA is a private sector-led initiative focused on getting the entire crypto community onboard in reducing the environmental impact imposed by mining.

The accord’s overall objective is to eliminate carbon-usage in the global crypto industry by prioritizing climate stewardship and support the entire industry’s transition to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2040.

The accord’s objectives are:

- Achieve net-zero emissions from electricity consumption for CCA Signatories by 2030. \

- Develop standards, tools, and technologies with CCA Supporters to accelerate the adoption of and verify progress toward 100% renewably-powered blockchains by the 2025 UNFCCC COP30 conference.

Who is involved?

The accord is supported by a total of 195 companies spanning both the private and publicly-traded sector, including such companies as Hut 8 Mining (HUT.T), Marathon Digital Holdings (MARA.Q), Mogo (MOGO.T), DMG Blockchain Solutions (DMGI.V), Ripple, Consensys and global accounting organization, KPMG. They approve of the accord’s objectives and are involved with various capacities to advise, develop and scale solutions to support the initiative. Becoming a support doesn’t necessarily verify that a supporter organization has completely decarbonized, but that they’re committed to net-zero emissions from electricity consumption with all of their crypto-activities by 2030, and with continual progress reports towards this goal using best industry practices.

Here’s a small sample of what some of the signatories are doing:

DMG’s Terrapool

A mining pool is a group of miners working together to increase their chances of finding a block at the group level, compared to that at the individual level. It combines individual computation resources with those of other members, which enhances the overall processing power and helps to everyone get the payoff faster.

DMG Blockchain Solutions terrapool is one such mining conglomerate. It includes a number of different companies at a number of different sizes, and each get to throw their computational power into a big pool—which can therefore be used to mine Bitcoin. How this works on an environmental level is that the pool can impose their own prerequisites on companies looking to onboard.

And DMG’s smart about this. They want environmental compliance, but they understand it’s not going to happen overnight. For example, if a potential new entrant to the Terrapool isn’t completely 100% environmentally friendly, they won’t get an immediate denial. Instead, they’ll get directions and assistance towards getting in line and a timeframe for completion.

Ultimately, it’s a good deal. A up and coming Bitcoin miner gets access to more resources than they would have normally, and the exchange involves jettisoning some of their nasty habits. Maybe instead of burning coal they source environmentally sound, renewable energy options.

DMG themselves have been way ahead of the curve when it comes to mining Bitcoin, so they’re coming into this from a position of strength. They’re ahead because their Bitcoin mining division uses all sustainable sources of electricity, and in this case, hydroelectricity, in their practices.

Mogo’s carbon offset

Mogo is essentially a fintech company with wide-ranging interests into crypto. They have recently launched an initiative they’re calling green crypto, which makes all bitcoin purchased on the Mogo platform climate positive. Basically, Mogo plants enough trees to offset the carbon dioxide emissions produced from mining every bitcoin they sell.

They’re going further than that, though. If you consider that 1.8 million bitcoin have already been mined to date, and an estimated 421,000 pounds of carbon dioxide emissions are released per Bitcoin mined, then that’s something of a problem. Mogo is addressing this problem by planting trees to offset 500,000 pounds of CO2 for each bitcoin on its platform.

Link

Link Global Technologies (LNK.C) recently closed their acquisition of Clean Carbon Equity (CCE), a trader of Verified Emission Reduction Credits in the carbon offset market. These credits are sold to customers to offset the CO2 emissions created by Bitcoin mining.

If all of that sounds Greek—here’s what it means:

Verified emission reductions are essentially a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) from a project that is independently audited, against a certification standard set by a third-party. Each verified emission reduction represents one metric tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions.

What it also means for LINK is providing carbon offsets in the digital economy, which means cash flow and greater logn-term revenue opportunities. So get paid and help the environment. Not a bad gig. The acquisition puts them on a carbon-neutral deadline four years ahead of the 2030 goal set by the CCA.

The Opportunity

The cryptocurrency industry isn’t as deeply embedded as oil and gas, or the automobile industries, and like it or not, regulations are coming to the cryptocurrency industry. Governments are already taking a good hard look at the environmental damage caused by Bitcoin (and some of the alts) and it won’t be long before the Bitcoin you buy from an exchange will come with add-ons of some variety. A carbon tax attached to capital gains—maybe. Some companies are going to run head-long into regulators peering into their environmental sustainability practices, and either need to rapidly upgrade or risk being shut down.

Miners like DMG Blockchain, Marathon Digital Holdings, Hut 8 Mining and other signatories of the CCA, are already well ahead of the sustainability curve. They’re out in front in a race that few know has even started.

—Joseph Morton