One of the things that pisses a lot of investors off about the resource sector is, the confluence of events most investors are looking for – revenues in and a smaller amount of expenses out – you know, ‘actually doing business’ – rarely occurs, because so few resource deals ever move into actual production.

Production means rocks are coming out of the ground, being milled and/or processed, and can be sold to end users. That may seem like the point of mining, but for a lot of mining executives, it’s not even on their business plan. They’d like to find some resources, prove they exist, then sell them to someone else who’ll do the hard work of raising millions and getting production programs rolling.

For every mining company in actual production, there are around 6.7 million mining companies that won’t get there. Obviously that figure is entirely made up, but not by as much as you’d hope.

Because you so rarely see an exploration shift into production in the wild, here’s what it looks like when it happens:

Ceylon Graphite Corp.’s (CYL.V) wholly owned subsidiary, Sarcon Development (Pvt.) Ltd., has started commercial production at its K1 graphite mining project at Karasnagla, Sri Lanka.

“We are finally in commercial production mode and look forward to selling our first container of Sri Lankan vein graphite — today we have brought two tons of raw graphite to the surface,” said Bharat Parashar, chief executive officer. “These three years have been a learning process and, whilst this is just the first step to creating a globally recognized graphite mining company, we are now much better prepared to develop our next sites and at a faster pace.”

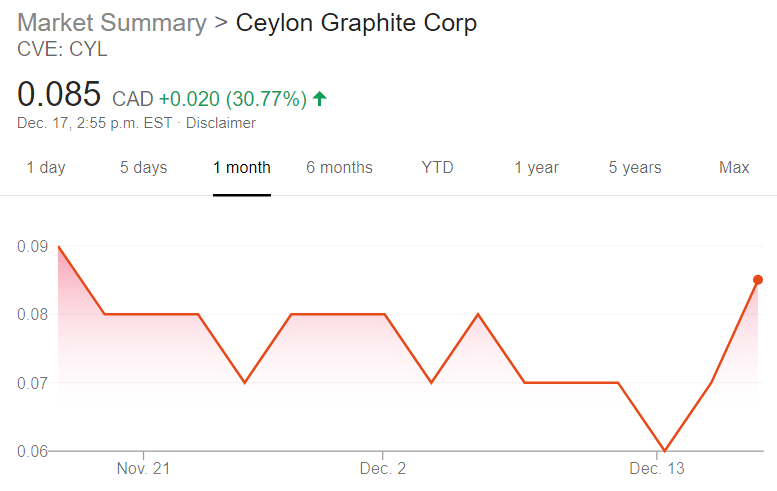

Production announcements have a habit of running a stock’s price up. Ceylon is up 38.5% on its news today.

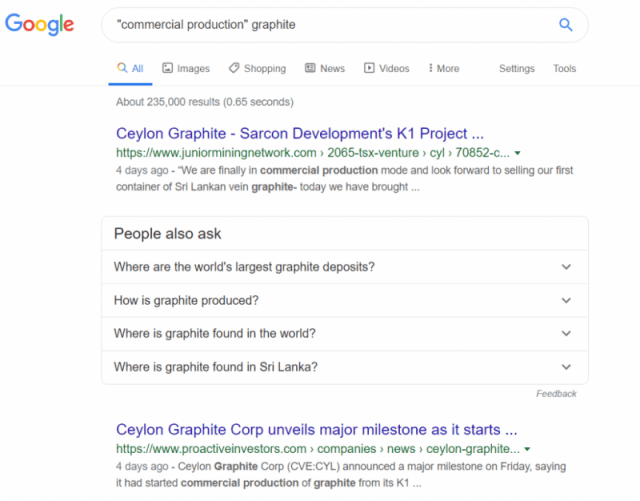

You wanna know how rare it is for a graphite explorer to move into commercial production? The last example I could find was from nearly a year ago, in Mozambique.

Hell, just google it, and Ceylon Graphite is the first thing you see.

Avoiding production is not always deliberate, though the most repeated trope about mining is you never want to ruin a good story by drilling into one. The path to production in most jurisdictions is long and arduous, expensive and political, and that’s after you’ve done the work to see if you even have anything worth digging for, which is also long and arduous, expensive and political.

When I spoke to merchant banker Sasha Jacobs about his Ceylon Graphite deal some three years ago, he said he was planning on taking his company to production ASAP, inexpensively and in quick time, and I kind of rolled my eyes. I wasn’t alone – nobody has given Ceylon Graphite an ounce of respect in the time since because, well, graphite is ass.

To be fair, graphite did have a short moment of glory when we all realized lithium ion batteries would need it and that existing supplies are all outside North America, but that hot moment was ended when it was subsequently realized nobody locally was looking to ‘ruin a good story’ any time soon.

Jacob was hellbent on changing that, partly because, as he put it back then, “You can literally see the graphite on the ground, there’s no shortage of it,” and also “the government here is basically letting us decide where we want to dig,” and “it’s so damn cheap to drill here, we can just buy a drill and be constantly working it, rather than bringing in crews for spot programs.”

All of that led to the one real selling point that brought a Canadian merchant banker to this part of the world; that he could move to production quickly and cheaply and without excessive burdens of a political nature.

Usually, you’d do a lot of advance work to achieve what’s called an NI 43-101, or a ‘resource estimate’, which would then be used to raise money and build your mine plan. To get there, you drill, you map, you triangulate, coagulate, masticate, flagellate, raise money like a champ and spend it hard.

Jacob went another route.

“We’re not going to go get a 43-101 in the short term,” he told me, “It’s so cheap to drill, so cheap to mine here, and the government is looking to monetize what’s in the ground, so we’re just going to do a small amount of drilling and then start digging into what we find once the permits are in place.”

This is a radical departure from the norm.

It’s a radical departure in ANY mining sector, but particularly in the graphite world.

Graphite isn’t a thing in most resource investors’ eyes because:

- You’d need to find it somewhere politically stable, that will be happy to export it for a fair price

- You’d need to find the right kind of graphite, that wouldn’t need intensive, expensive, and environmentally destructive processes to make it useful for industry

- You’d need to get it into production now, while the shortages are there, and not in eight years

Drag any old graphite deal in North America out for a twirl and what you find out is they don’t hit those three notes in the right way. There are local graphite exploration sites that are years and many millions of dollars from production. There are sites in production, but they’re in places in no hurry to share what they have for cheap, or even with a premium price attached. And there are whopping great piles of resources that feature low quality ore that would be expensive to process and not pleasant to be around while that’s happening.

Ceylon Graphite runs the table.

The slogan for the company is, ‘The World’s Finest Graphite’, and though that’s a play on the old Ceylon Tea slogan, it’s also a little bit true.

Ceylon Graphite Corp. has received assay results of laboratory testing of graphite samples taken downhole in the shaft at its M1 site in the Malsiripura area in Sri Lanka. This new test result indicates a naturally occurring carbon content (Cg) of 99.2 per cent which is vastly superior to most other natural graphite sources globally. The laboratory testing was done by the Sri Lanka government’s Geological Survey and Mines Bureau’s laboratory.

Ceylon’s graphite is high quality, which means it doesn’t have to be processed as hard as does ore from other places, which makes it dirt cheap to get to an end user, and useful when it gets there.

School time: You may recall a few years back when Samsung phones were igniting in people’s pockets. That came from low quality materials getting through into production lines. Nobody wants a repeat of that, so high quality graphite is a really important thing to end users.And the highest cost involved in getting product to production lines is the processing, which basically involves baking the shit out of the raw graphite, often several times.

To process raw graphite into an end useful material, the ore is crushed, then milled to round it off, then put through screens to sort it into similar sizes, then has a binding material mixed in, then is punched into die molds and extruded with ultra high pressure to properly shape it into bars or tubes, it’s then baked at 1200 degrees Celsius to burn off impurities and turn that binding material into a volatile component, and then it’s all baked in a vacuum at 3000 degrees Celsius to form graphite crystallization.

Do not try this at home.

That process is expensive and dirty, and often has to be repeated at several stages because lower quality graphite doesn’t become high quality graphite unless you’ve worked hard at making it so. Thus, a high quality graphite coming out of the ground makes for a better process, a better price, a better timeline, and a better end product. Right now, graphite buyers will take what they can get, and if they have to run their ore through this process a few times to get it to a place where it’s usable, they’ll do that.

But, boy howdy, what they wouldn’t do for a nice clean graphite coming right out of the ground.

ENTER CYL.

The company is presently in discussions with several end-users and processors of natural graphite regarding sales contracts. Sri Lankan graphite is known to be amongst the purest in the world.

This is big. I know a lot of investors don’t touch resources because it’s a long, slow process that, at any point in the journey, can suddenly become unfeasible. Commodity prices drop below economic recovery prices, local governments deny permits, grades of ore don’t pass muster, drilling comes up with less ore than desired, executive teams take their foot off the gas to ensure another few years of salary, it can be a real dogs breakfast.

But Ceylon has pulled the old Integra Gold model out of cotton wool. For the uninitiated, Integra took over a piece of property that hadn’t worked out for several previous owners, and rather than continue down the usual path, just drilled into where they knew gold to be, and immediately began yanking it out of the ground on a small production run. That production financed more drilling, and more production, until they had a fully working mine and a big 9-figure buyout.

Ceylon is treading the same path, starting with a small dig that will finance subsequent digs.

Sarcon’s drilling and exploration program will increase in its momentum as the company looks to increase its footprint to at least five mine sites over 2020.

CYL hasn’t had much love for several reasons:

1) It’s graphite. We’ve been through this.

2) It’s in Sri Lanka, and that’s unknown territory for a lot of North American investors.

3) It’s small. Though being in production is a big deal, it’s not the size of production you usually see, where $100 million has been spent on a massive quarry, fleets of earth-moving trucks, and a small town built to supply the employees with beer and women.

But this mine has been brought into reality for a small amount of capital, it’s bringing out real, high quality ore, there’s no shortage of expansion options around it, and it should be able to self finance going forward.

That paragraph above, where CYL says its talking to end users – this too is big. Selling directly to a battery manufacturer, as an example, means they’ll be able to do their own deals, and charge a premium for their high quality. For a lot of end users, being able to lock down supply for years going forward is a very important thing, and at a $4 million market cap, buying out the company to lock that supply down is a walk in the park.

That’s right – I said a $4 million market cap. Even after jumping 38.5% in the day, it’s JUST A $4 MILLION COMPANY.

Sell a couple of containers of graphite and that should catapult, realistically. Sell it to a recognizable end user and it should become a millennial stock, not an old timey mining guy stock.

If you’re the kind of investor that likes putting your money into renewable energy, graphite is a thing you should pay attention to.

If you’re the kind of investor who wouldn’t to that usually, because mining takes forever to be real, Ceylon Graphite is a thing you should pay attention to.

And if you just straight up like the idea of getting in on a company that is valued at a price where a double or triple is pretty damn possible and the risk has been lowered hard and the timelines accelerated hard and they’ve done what they said they were going to do… well.

— Chris Parry

FULL DISCLOSURE: Ceylon Graphite is an Equity.Guru marketing client, and has been for years and, what do you know, they did it.