Ever since the greasy arrogant squirrel-faced grin of Martin Shkreli turned our collective stomach, big pharma has come under fire for their pricing practices. Pharma execs, often paid up to 300 times more than their average employee, shot back that research and development costs were crippling and all that needed to be paid for with healthy profit margins. Should we just buck up and shut up, or are we witnessing the brain death of big pharma?

Ever since the greasy arrogant squirrel-faced grin of Martin Shkreli turned our collective stomach, big pharma has come under fire for their pricing practices. Pharma execs, often paid up to 300 times more than their average employee, shot back that research and development costs were crippling and all that needed to be paid for with healthy profit margins. Should we just buck up and shut up, or are we witnessing the brain death of big pharma?

Well, these exorbitantly compensated corporate leaders aren’t exactly lying; drug development is outrageously expensive and it’s getting less affordable every year. A recent study by Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development pegged the estimated cost of developing a drug and maintaining it through its commercial life cycle at approximately USD$3.0 billion dollars.

So just how much is a billion dollars? Well, if you were that floppy coifed WeWork CEO ‘toiling away’ for a $1.0 per second or $3,600 per hour (just kidding, he was paid much more with stock), it would take you almost 32 years to make a billion dollars and a lifetime to cover the costs of bringing new medicines to market.

So just how much is a billion dollars? Well, if you were that floppy coifed WeWork CEO ‘toiling away’ for a $1.0 per second or $3,600 per hour (just kidding, he was paid much more with stock), it would take you almost 32 years to make a billion dollars and a lifetime to cover the costs of bringing new medicines to market.

According to the Tufts study, these costs go toward testing new indications, new formulations, new dosage strength and regimens, as well as monitor safety and long-term effects as required by the FDA. On the surface, it looks as though sector giants like Biogen (BIIB.NASDAQ) and Purdue Pharma are constant stewards burdened by debt for the common good, but as Purdue pays dearly for drugging America, people are pulling back the curtain on Pharma’s scientific wonderland and finding a dull-grey world of reckless acquisitions, endless lawsuits and criminal negligence – all in pursuit of obscene profits.

Business as usual?

Let’s focus on biotech as a grab sample of big pharma’s chicanery. Biogen formed in 1978, going public in 1994 with its wonder drug, a recombinant beta interferon (RBI), AVONEX, approved by the FDA for treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) as an orphan drug.

The orphan drug designation is given to candidates seeking to treat a rare disease or condition upon the request of a sponsor. The classification grants exclusivity rights for seven years, allowing the drug’s manufacturer to squeeze whatever money it can from the product before competitors and generic drug developers move in.

On the surface, this classification promotes research by granting ample opportunity for developers to recover costs, but ultimately, it’s an old boys club muzzling market innovation in favor of dominance and profit.

So, despite gaming the system with the help of the FDA, Biogen was awarded the annual National Medal of Technology by Bill Clinton in 1998.

So, despite gaming the system with the help of the FDA, Biogen was awarded the annual National Medal of Technology by Bill Clinton in 1998.

AVONEX lost momentum around the turn of the millennium and Biogen was acquired by Idec Pharmaceuticals in a $6.8 billion stock swap in 2003. The development of a new drug is almost cost prohibitive compared to acquiring someone else’s drug which has either already undergone clinical trials or is in the midst of them. Idec therefore snapped up Biogen and its next pipeline winner, Amevive, which had been developed as a therapeutic treatment of psoriasis.

Amevive received FDA approval in 2003 and newly merged Biogen Idec proclaimed it would sell $85 million of the drug that year and $500 million of it in 2005. With 1.5 million adults in America suffering from moderate to severe psoriasis, investors bought into the plan.

Unfortunately, Biogen Idec was in trouble. Sales for AVONEX had flattened and Amevive’s prospects were dim as a drug developed by rival Amgen (AMGN.NASDAQ), had already been approved for the treatment of rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, and was five years deep in its commercialization. This meant that doctors prescribing treatments for their patients would be more familiar with and trusting of Amgen’s offering. To add insult to injury, it was suggested that Amgen’s Enbrel worked on a higher percentage of patients than Amevive.

This challenge cut Amevive off at the knees and Biogen was only able to offload $48.5 million worth of the drug in 2005, less than a tenth of what execs speculated they would sell. Shortly after this embarrassment, Biogen Idec packaged Amevive and sold it off to Astellas Pharma for a diminutive $60.0 million after listing total of $1.84 billion in R&D and in-process R&D write-offs.

This challenge cut Amevive off at the knees and Biogen was only able to offload $48.5 million worth of the drug in 2005, less than a tenth of what execs speculated they would sell. Shortly after this embarrassment, Biogen Idec packaged Amevive and sold it off to Astellas Pharma for a diminutive $60.0 million after listing total of $1.84 billion in R&D and in-process R&D write-offs.

Without an itemized split, there’s no way to tell how Amevive lost relative to the rest of Biogen’s pipeline, but if you divide the total equally between Biogen’s pipeline, Amevive’s share comes to $368 million and it was dumped for a sixth of its invested worth. To add insult to injury, Astellas voluntarily discontinued US sales of Amevive in 2011 due to poor marketplace performance.

Biogen meanwhile, needed another flagship and slid into the world of neuroscience with aducanumab, a drug candidate for the therapeutic treatment of Alzheimer disease which affects almost six million people in the United States and is projected to plague nearly 14 million U.S. citizens by 2050 – that’s one more American diagnosed with the disorder every 65 seconds.

Neurology is a hybrid of such higher studies as molecular biology, biochemistry, physics and computational biology. With so many interactions and conditions at play, treating neurological disorders seems to be roughly equivalent to entering a dark room with a shotgun in the hopes of hitting a fly. You may eventually get the fly, but you may never hit another one because you basically have no real idea how you hit the first one anyway – and the potential for collateral damage is astronomical.

Yet when you’re forced to witness a loved one’s soul evaporate into the husk of a confused and frightened stranger, much is forgiven. To better understand Alzheimer disease (AD) and aducanumab’s potential, let’s touch on a little science.

Dr. Alois Alzheimer identified has namesake in 1906 and noted two hallmarks of the cognition killer:

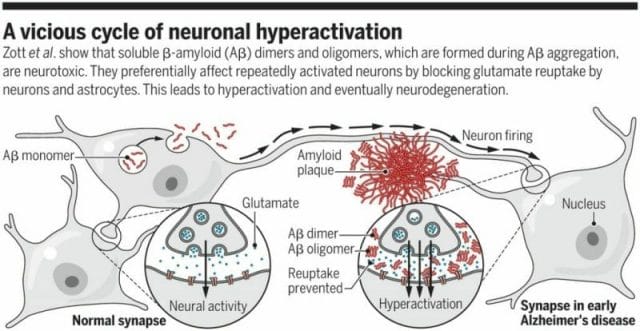

- Plaques – are tiny protein deposits called “beta-amyloid” or A-beta. These proteins float about inside the brain blood barrier harmlessly as monomers. Proteins tend to fold in a predictable fashion and with a lot of math, you might even be able to predict where they will bend but there are times when they fold irregularly, creating disordered monomers. These messed up monomers collect inside your brain, blocking signal transference between neurons, eventually killing the affected cells.

- Tangles – are fibril clumps of the Tau protein. Pristine Tau proteins provide the framework for a sort of parallel railroad track between dendrites and axions, carrying nutrients and other necessary materials to each node making up your neural network. This microtubule (MT) binding protein keeps the pathway open in a healthy mind, but when it mutates, it can detach from the MT which implodes without Tau’s support cutting off healthy cells which in turn, die.

Popular theory is that both plaques and fibril clumps of Tau can be controlled through antibodies which affix themselves to targeted sites on the proteins before they fold, preventing the toxicity of their twisted nature.

Popular theory is that both plaques and fibril clumps of Tau can be controlled through antibodies which affix themselves to targeted sites on the proteins before they fold, preventing the toxicity of their twisted nature.

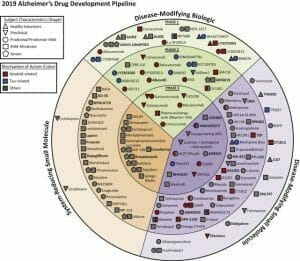

Biogen’s big idea centered around this theory. The company spent billions developing aducanumab, but it wasn’t the only one chasing this elusive dream. According to a 2019 report by the U.S. National Library of Medicine, there are 132 agents in clinical trials for the treatment of Alzheimer disease (AD). Twenty-eight of those agents are in phase 3 trials, 74 agents are in phase 2 trials and 30 agents are in phase one.

The fight in AD modifying biologics is over the importance of selectivity. Biogen cast a wide net in the development of its candidate. Aducanumab was made to go after plaques, which some researchers claim is mostly a non-toxic form of amyloid beta. To have any noticeable effect, high dosages are required.

The fight in AD modifying biologics is over the importance of selectivity. Biogen cast a wide net in the development of its candidate. Aducanumab was made to go after plaques, which some researchers claim is mostly a non-toxic form of amyloid beta. To have any noticeable effect, high dosages are required.

This massive assault is prone to cause conditions such as edema when an excess of watery fluid fills your skull, which when it comes to your brain, really isn’t a good thing. Since your cranium hardens in early childhood, it isn’t going to expand to accommodate the additional fluid. So, painful at the best of times, edema also has the potential to squeeze the life out of you, literally. Cruelly ironic for a drug supposed to protect what makes you, you.

Billions in backing and all the necessary connections kept Biogen on the path to commercialization as aducanumab entered the third phase of clinical trials in 2015. In July 2018, after Biogen’s presentation at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, the randomization of its BAN2401 trial was called into question as researchers carried out analysis and guided new test subjects toward dosages that were most likely to work, so the incredibly high test results were skewed. There should have been cautious optimism at best, but Biogen plowed ahead with BAN2401 and aducanumab wearing a 12-mile smile.

In March, Biogen stock was pummelled after the company announced its favorite AD drug candidate failed an independently run futility analysis and was unlikely to meet their primary endpoint of proving aducanumab had a scientifically significant impact on the progression of AD.

Is Biogen’s rot endemic?

We look at these developers as gods who hold our future within the chemistry of their billion-dollar biologic life-savers and can easily pass off Biogen’s wild miss as an honorable try, but was it just an industry-perpetuated sham? Is big pharma any better than Silicon Valley?

We look at these developers as gods who hold our future within the chemistry of their billion-dollar biologic life-savers and can easily pass off Biogen’s wild miss as an honorable try, but was it just an industry-perpetuated sham? Is big pharma any better than Silicon Valley?

The climate for AD research is grim. A study of big pharma AD clinical trials by Biomed Central revealed a 99.6% failure rate of all trials from 2002 to 2012.

Unfortunately, researchers weren’t mandated to list their work on clinicaltrials.gov until 2007 so data prior to that is most likely incomplete, but it’s not that far off. When the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) required listing with the government site before allowing publication in 2005, big pharma participation greatly increased – after all, if your clinical trial cannot be accessed, cited or verified without publication, it means nothing. Kinda like positive research propping up the pseudoscience of magnetic bracelets which resulted in Power Balance coughing up $57 million in fines in 2011 and admitting its product was a con.

Unfortunately, this public liability isn’t limited to fringe wingnut ventures, big pharma is hemorrhaging over Purdue’s rampant opioid trade.

Purdue’s Sackler family was ordered in April this year to hand over $270 million to the State of Oklahoma for all the grief they caused, while two Ohio counties won $215 million cash from opioid distributors. As well, Israeli drug developer, Teva, braced for legal challenges when it added to its defense fund, setting aside $1.2 billion for any upcoming class action suits.

Several state attorneys may have put forward a $48 billion-dollar proposal that would see an end to the litigation, but other state legislators claim Purdue Pharma isn’t paying nearly enough for its hand in the deadly epidemic killing 100-plus people a day in America alone.

So, the lawsuits won’t be ending anytime soon. It’s dog-eat-dog in big pharma because the only way to survive is to get a patent, defend it vigorously and then find another patent quick.

So, the lawsuits won’t be ending anytime soon. It’s dog-eat-dog in big pharma because the only way to survive is to get a patent, defend it vigorously and then find another patent quick.

Since drug development processes are incredibly specialized, painfully long and involved, almost no big pharma company has the intellectual or capital power to independently keep knocking them out of the park from scratch. They have to build off one another’s learnings, but their profit system works directly against this.

In the world of big pharma, you don’t usually build your IP after your first hit, you buy it. And if you can’t keep the cycle up through acquisitions, its time to tweak your failing product just enough to apply for a new patent. Now you can continue milking your customers up to $60,000 a year for a drug you haven’t really improved but continues to extend your exclusive control.

That’s exactly what Biogen just did. Even though it pulled aducanumab out of its pipeline, the company’s acceptance of its failure with the EMERGE and ENGAGE phase three clinical trials of aducanumab was short-lived.

Biogen announced at the end of October it would dust off the disappointing data because the independent futility analysis was wrong. It is Biogen’s considered opinion that the EMERGE trial in phase three had met its primary endpoint, as the high dose group using 10 or more mg/lg dosages experienced a significant slowing of cognitive decline.

Of course, the ENGAGE trials in phase three were supposed to mirror EMERGE, and they failed to meet their primary endpoint. One would think the mirroring would show high dose subjects in both trials having scientifically significant impacts on cognitive decline.

So, is this reversal a legitimate contention of science or is Biogen pulling rabbits out of its ass to resurrect a failed drug candidate for yet another round of trials, which it will then use to maintain market cap and induce even more financing? Or is this the death knell for aducanumab?

Biogen’s recent announcement that it would release Vumerity, a MS therapy drug, next year comes on the heels of its current MS workhorse, Tecfidera, coming under patent challenges that threaten to introduce an army of generics on the market.

At this point, it feels reasonable to wonder if Vemerity, which only helps a fraction of MS patients with gastrointestinal issues, is a modified version of Tecfidera that will not only allow Biogen to gain patent protection once again but orphan drug status as well.

This is the kicker. The argument in big pharma for the outlandish pricing of therapeutic drugs is that innovation is costly and needs to be absorbed by you and me so these companies can continue making our lives better. The truth is that most of the costly research is already funded by government and NGOs. Of the $3.0 billion dollars needed to service a drug through its commercial life cycle, big pharma companies like Biogen only pay a fraction of that cost; the majority of important scientific research is already backed by you and me, the average taxpayer. So why are we forced to pay $1,100 per week for Victrelis, a Hepititus C treatment drug manufactured by Merck?

Even though the market reaction to Biogen’s announcement of failure in March was extreme, the bounce back was also extreme. I believe Biogen is currently trading at one hundred dollars more than it should be.

Companies like Biogen have reduced drug discovery to a litigious game of three card Monte, where patents act as roadblocks to efficient innovation and drug developers are little better than cannibalistic rainmakers. I thought Shkreli would have ruined it for everybody, but if big pharma continues to choke dangerously on its own greed, its impending brain death is bound to take us all down.

–Gaalen Engen