The cryptocurrency markets are considered to be the wild west of trading and it’s a well-earned distinction.

Normally if you’re a little light on your due diligence and get caught in a cryptocurrency scam, you won’t ever learn about it. You’ll log onto what you might have thought was a solid exchange and discover that either your stake or the exchange is gone, or maybe both.

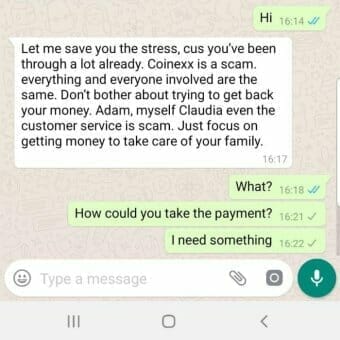

Maybe you sent some money to a crypto-advisory firm with a professional looking website that promised big returns. You won’t hear from them either when they disappear. Or maybe you’ll end up like Australian couple Nick and Josie Yeomans, who put their trust and AU$20,000 into coinexx.org (which is different from coinexx.com), and received this shock via Whatsapp:

Rubbing salt in the wound is just evil. Naturally, the site has been suspended.

That’s the downside of an unregulated market, though. Less restrictions mean less government hand-holding from pearl clutchers afraid of what they don’t understand, but absolutely no restrictions means anything goes.

There’s a real problem here.

Here are a few examples of what to look out for.

Fraudulent ICOs

Here’s what we wrote about ICOs earlier this year:

An ICO (or Initial Coin Offering) is an unregulated fundraising method using cryptocurrency in support of a new project. They’re used mostly by tech startups looking to avoid the strict regulatory process of capital-raising required by venture capitalists or banks. During an ICO, a percentage of the cryptocurrency is sold in exchange for fiat funds, or other cryptocurrencies, with the biggest coin being Bitcoin.

A 2018 study performed by Bloomberg concluded that almost 80% of 2017 ICOs were scams.

“[As] a percentage of the total number of ICOs,” reads the report, “we found that approximately 78% of ICO’s were Identified Scams, ~4% Failed, ~3% had Gone Dead, and ~15% went on to trade on an exchange.”

Earlier this year, Canada saw its first high profile ICO fraud takedown.

Kevin Hobbs and Lisa Chang held an ICO for their Vancouver-based blockchain consulting firm Vanbex, and raised $22 million. After launching the FUEL token, they told their investors that their cryptocurrency would grow substantially in value.

Then instead of using the funds raised in the ICO to grow the company and bring some value to their company, they bought themselves a $3.7 million condo in Toronto, a $4.2 million dollar condo in Vancouver, gambled away $1.8 million, and bought themselves a Lamborghini.

False claims

This is probably the largest bit of fraud cryptocurrency and blockchain investors have to deal with. It’s endemic, common enough to be noteworthy in the non-crypto investment world. It’s when a company states they’re going to do something, or states they have something, they do not have.

The next story could actually cover two different categories, as the cryptocurrency enterprise behind ‘OneCoin’ operated their business with the multi-level structure common to pyramid schemes wherein each investor gets a kickback for bringing in new investors.

Except the kickbacks were in OneCoin.

OneCoin could not be exchanged or traded in for any other coin, especially after its lone exchange, OneCoin Exchange xcoinx was taken down in November 2017.

Members bought education packages ranging from 100 euros to 118,000 euros. Each package contained “tokens” which could be used to “mine” OneCoins. OneCoin was supposedly aided by servers at two sites, in Bulgaria and Hong Kong.

Manhattan U.S. Attorney Geoffrey S. Berman said:

“As alleged, these defendants created a multibillion-dollar ‘cryptocurrency’ company based completely on lies and deceit. They promised big returns and minimal risk, but, as alleged, this business was a pyramid scheme based on smoke and mirrors more than zeroes and ones. Investors were victimized while the defendants got rich. Our Office has a history of successfully targeting, arresting, and convicting financial fraudsters, and this case is no different.”

The company promised large returns and gave nothing back and between the fourth quarter of 2014 and the third quarter of 2016 OneCoin generated 3.353 billion euros ($3.769 billion) in sales revenue and profits of 2.232 billion euros ($2.509 billion).

The comment’s section on the second link is an especially harrowing read.

Buying crypto through third party apps like PayPal

There are plenty of sites digitally hawking third-party software you can install on your computer or phone that will clean up the inherent problem behind using other third-party software (like PayPal) to buy cryptocurrency.

Just save yourself the hassle and don’t. Get a wallet and buy it the traditional way.

The problem lies in the time differences between PayPal’s comparative speedy money-transfer service, and the time it takes for a block to close to complete a cryptocurrency transaction. On average, a Bitcoin transfer will take about an hour to clear, giving the cash recipient the ability to cancel the order before the block can close. The person then closes out their account and disappears with your money and their bitcoin.

There are tools on the market that offer is a form of escrow-service that will hold cash in trust while the block clears. This isn’t recommended. Buying any untried and untested financial instrument regardless of the amount of diligent research still carries too much risk of either being hacked from outside, or stolen by the company issuing the app.

Remember, when your money’s gone, there’s no recourse to get it back. Cue the wild west analogy again.

When investing in cryptocurrency, the general rule is that you want as few points of contact as possible. If you use PayPal and an associated escrow-service app, then you have at least three—PayPal, the app, and whatever exchange the seller used. By minimizing to two points of contact, such as a mutually-shared exchange and a (cold) wallet, you minimize risk.

Ponzi Schemes

The Ponzi scheme itself actually refers to a confidence scam in which the operator pays high returns to attract investors, and encourage current investors to add more money. When other investors begin to participate, a cascade effect begins. The schemer pays a “return” to initial investors from the investments of new participants, rather than from genuine profits.

A few months ago thousands of people in Ladysmith, a city 365 km south of Johannesburg, South Africa, lined up and slept overnight at the offices of investment trust Bitcoin Wallet, to be the first to take advantage of what was promised to be easy a 100% return on their investment in fifteen days.

At the time, the scam was generating R2 million ($135,000) per day.

Now on July 4, 2019, thousands of people have shown up once again to the offices of Bitcoin Wallet to find out where their money went, and found the doors closed and locked.

Regulation or Self-Regulation:

American mythology offers that the wild west was tamed by hard men willing to stand up and throw iron at the criminals and thugs who were making life difficult for good God-fearing Christians. It’s a romantic vision and a fairly common trope in modern storytelling; the lone gunslinger, wandering into town, cleaning up the corruption with his Colt .45 peacemakers.

And like most of American history: it’s revisionist, nationalist bullshit.

The reality of the taming of the wild west has more to do with sociological and cultural shifts, such as technological advances, increased access to education and opportunities, and maybe the emergence of a new foe in Europe, than to anything remotely related to American essentialism.

It’s likely the cryptocurrency markets will end up the same way. Through cooperation and trust between private firms that want to make money in a safe marketplace, and governments, who rendered powerless to act by decentralization, don’t have any other choice.

After all, what makes Bitcoin and other decentralized currencies attractive alternatives to traditional central-bank controlled fiat (decentralization, immutability and privacy) are the same traits that attract criminals. That’s why it will be an ongoing process with no set finish date.

And it’s also why no government body in the world will be able to stop it, even if they ban it outright.

Some will try, though.

Most countries have posed restrictions on investments in cryptocurrencies, and the extent of which varies from one jurisdiction to another. Some (Algeria, Bolivia, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, and Vietnam) ban any and all activities involving cryptocurrencies.

Qatar and Bahrain bar citizens from any kind of activities involving cryptocurrencies locally, but allow citizens to engage outside their borders. There are also countries that, while not banning their citizens from investing in cryptocurrencies, impose indirect restrictions by barring financial institutions within their borders from facilitating transactions involving cryptocurrencies.

On the far end of the poll are the countries like Spain, Belarus, Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands, that have either created a cryptocurrency friendly regulatory regime, and Venezuela, the Marshall Islands and the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, which has created their own cryptocurrency system.

Canada, the United States and the U.K. are in between the two poles. The U.K. recently banned cryptocurrency derivatives and exchange traded notes, while both Canada and the U.S. are figuring out how to regulate cryptocurrencies.

Where ICOs are considered, the U.S. is ahead of the game. The SEC has recently started the bull rush there by taking Kik Interactive to court. While in the Netherlands, the rules applicable to a specific ICO depend on the function of the token, with different rules governing a security or a unit in a collective investment, with each assessment made on a case by case basis.

Only China, Macau and Pakistan ban ICO’s altogether, while most other countries intend on regulating them.

But there’s only so much that governments are going to be able to do to regulate cryptocurrencies because of their international, decentralized nature. The Winklevoss twins, the owners of the Gemini Trust and cryptocurrency exchange, and also known for being duped out of Facebook (FB.Q) back before Facebook was Facebook, hired Nasdaq Inc. last month to conduct digital surveillance of coins trading on their exchange.

The twins are urging trading platforms to band together to form a group that would serve as a self-regulator for the industry.

“There are a lot of carcasses on the road of crypto that we’ve seen and learned from. At the end of the day it’s really a trust problem. You need some kind of regulation to promote positive outcomes,” Cameron Winklevoss said.

The new wild west will only be won through collaboration.

Keep hodling.

—Joseph Morton