PROLOGUE: Cannabis companies, as we know them in our minds, rarely exist.

Oh sure, some have buildings and staff, some grow things and others might even have a license. But even those with big buildouts and massive market caps are, for the most part, a promise of what’s to come, maybe, some time, kinda.

But that isn’t to their detriment. In the topsy-turvy world of legal cannabis, the truth is the companies making the most revenue run the biggest losses. The companies with the biggest stock runs are running on rumour, not news.

We accept this inversion of norms as investors because cannabis companies are early, and face many challenges not found in other sectors, dealing with laws being changed on the fly and changing consumer wants and not being able to market themselves and having different distribution in every province.

As it turns out, the product isn’t weed. The product is promise.

It’s always been this way. Back in early 2014, when Satori Resources (BUD.V) became the first big marijuana company flyer, on the back of a news release that didn’t even mention the word cannabis, the sector has rewarded ‘I’m gonna’ and all but ignored ‘I am’ as a way of doing business.

That year, when Canadian courts mandated the government should allow medical marijuana for patients with prescriptions, a spate of mining explorer executives who had never found anything to mine thought they’d roll the dice on cannabis and flew up the valuation charts without having to actually show their work.

You couldn’t blame them for that. They literally couldn’t show their work, because saying you were getting into weed back then would see the TSX Venture Exchange halt a company for an extended ‘change of business’ period, which might see stocks that had been doubling in value weekly prevented from trading, right as cash was falling from the sky.

Toronto, Ontario – February 12, 2014 – Satori Resources Inc. announces that management intends to evaluate new projects, including, but not limited to, opportunities in agriculture, medical, technology, finance, and resources.

At this time, no transactions are in place, nor is there any assurance that a new project will be concluded in the future.

Few knew it at that point, but that mealy-mouthed pubco garble was the opening salvo in the creation of the Canadian cannabis industry. I may have been the first journalist to figure out what Satori was getting at, helped along by the knowledge they owned an old mineshaft in Flin Flon, which the Canadian government had once made famous when it grew early medical weed in abandoned mines to keep it away from onlookers (and US crop dusters).

When I wrote about this news release and pontificated that it looked like maybe they were planning to get into weed, the stock took off like a rocket, and nothing was ever the same.

A capital pool corporation (CPC), LW Capital Pool Inc., had actually beaten Satori by a month in announcing it would roll in a nascent weed business in Tweed, which would eventually become Canopy Growth Corp (WEED.T), but back then you couldn’t trade that stock yet.

But Satori? You could trade the hell out of that, and plenty did, especially when it announced it’s ticker symbol would be BUD.

Within a month, 40 other miners had dropped the same news release, causing the TSX-V heart palpitations. But it was the arrival of the new Canadian Stock Exchange (CSE), which quickly welcomed weed plays and took a looser perspective on compliance, that saw things really get gnarly.

The CSE had looked like a dumb idea early on, before cannabis companies realized they’d let you do pretty much anything you want if you listed there, and so the third tier exchange became colloquially referred to as the Cannabis Stock Exchange and bragged loudly about the deals flocking to it.

What made the CSE attractive to stock promoters was its informality: they didn’t get all up in your business. And if you didn’t have a business yet, you’d be good to go in quick time as long as you had a business plan and a listing fee.

From the outset, all cannabis companies have played a shell game to some degree. Nobody has been pure, though many have found purity as the market has gotten smarter.

Initially, the big promise was ‘we’re going to get a license.’ That was enough for a while to propel a stock from $0.03 to $0.15. Then it was ‘we’re really close to a license.’ That was good enough to get a company to $0.40. Actually getting a license didn’t happen for more than a handful for years, but companies that could tell a good story while we waited were still rewarded through that time with financing dollars and amplified stock prices.

Funny thing – when those companies actually did what they said they would do – when a license arrived, as an example – the successful party often didn’t get rewarded by the market. Stocks would actually drop on the arrival of expected good news. As laws began to take shape and as companies were increasingly asked to show rather than tell, the sector would slump.

But if someone announced they were going to build a million square feet of greenhouse by the airport in Edmonton, well that would pop the whole market, and others would follow, bragging about 2 million square feet, or 4, or 7.

CEN Biotech (FITX.OTC) was the first fraud to play the ‘we’re going to build more square feet than anyone’ game, making the claim so early, and with figures so ridiculous, that they made their way into US late night talk show host’s monologues.

When we exposed the CEO was faking it all, that it wasn’t really his signature on company documents, that employees listed as people to call for information weren’t actually people, that the town they planned to build in didn’t have enough water to let them use any, and that the actual building they had wasn’t permitted for anything more than a security fence, the fraud became so obvious that Health Canada did something they’ve not done before or since.

They actually risked a lawsuit and told a license applicant, ‘You’re never getting one.’

But while FITX was early with their bullshit, others would make the same claim further down the line, with about as much to back it, and actually be taken seriously with runs in share price that inflated market caps beyond common sense.

Eventually, building the biggest greenhouse known to man wasn’t moving the needle anymore, so the hype moved to oil extraction, or purchasing brands that had no actual presence in the marketplace but had a nice logo, or buying competitors for an inflated price, which gave merit to your own inflated price as a comparable.

Eventually, the hype moved to foreign assets, and that hype was so nuts that companies like MedMen (MMEN.C) could come to market with insane executive compensation deals and nutty voting power structures and balance sheets that have more red ink than a Chinese flag factory.

“Here’s the thing about a foreign asset,” says Marc Lustig, founder of CannaRoyalty, now Origin House (OH.C), who built his billion dollar company on the back of asset acquisition in all kinds of verticals in the US and Canada. “If you’re buying something in Eastern Europe or South America, who’s going out there to see if it’s real? If you buy something in California, it’s right there, we can see it, we can do our due diligence on it, we can check accounting, but some of these deals are done in places where nobody is going to go see if it’s real, and that’s by design.”

When an asset is in Lesotho, or Uruguay, or Malta, I’m unlikely to take a plane there, hail a cab, and say ‘take me to the weed grow facility’ because, while I want to do my due diligence, what’s considered ‘due’ doesn’t usually mean getting a visa approved.

And nor should it. Public companies are designed to be communicative with their shareholders, or potential shareholders, or short sellers for that matter. They create investor presentations and put out news and file documents and market themselves to you with a view to proving that they are what they claim to be.

Not everyone is good at this. Some executive teams are, quite frankly, terrible at their job.

But there’s unwittingly terrible and there’s suspiciously terrible. The Wayland Group (WAYL.C) is so terrible at what they do, that the more we dug in, the more we suspected what was going on with this company was a deliberate attempt to obfuscate and mislead.

To be clear, we began digging in because we have a beef with the company.

[drama alert]

Earlier this year, Equity.Guru had been accused by Wayland Group CEO Ben Ward, on Twitter, of attempting to blackmail him, alleging we told him if he didn’t buy a market awareness program from us, we’d write mean things about him.

The accusation was completely false. It was defamatory, without doubt, and because it involved allegations of criminality, it was especially damaging in a way most judges don’t appreciate.

We hadn’t actually talked to Ward at all, and hadn’t written about his company for months. A former Equity.Guru writer had posted to social media that he was planning a story on the company, but that writer was then running his own site and had nothing to do with us.

Several years earlier, a third party had attempted to bring our company and Wayland together, around the time of Wayland’s debut under the Maricann name, but neither party pursued a commercial arrangement, and we had been out of contact for several years when Ward alleged to the world we were committing a crime.

That’s not something we do, nor have ever done, so our response was immediate and to the point. Take down the words, apologize for them, clarify the situation, and explain how it happened – or we’d take legal action.

In fairness, Ward took the offending claim down the following day, and for a time took his social media accounts private, offering a ‘sorry you’re sorry’ admission that he couldn’t prove we’d actually done what he’d said we’d done with evidence but refused to apologize which, rather than fix the situation, left it hanging open.

Or reputation is important to us, especially in an industry that is regulated. And with a business model that places trust at the highest level, we demanded the apology again, or we’d sue.

‘You sue us, we’ll sue you right back.’

The process for winning a defamation suit, even when you’re 100% in the right, even when the other side has ignored multiple chances to make things right and spurned generous efforts to give them a way out, even when you can show legitimate damage to your business and reputation by their actions, is problematic in Canada.

Case after case shows the ‘winning’ side in a defamation case will often spend tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars filing suit and paying retainers and going through mediation, and eating up time in court, only to win a cursory award that doesn’t cover the actual loss.

And, even when you win costs, you usually get back only a tiny percentage of your fees rather than the actual money spent.

Generally, if you file suit at all, it’s because you’re determined to have a court prove the other side was wrong, at your own expense.

It appeared Wayland was playing chicken rather than making things right, so we considered our options. Our legal advice was, we’d almost certainly win. Not only was the tweet dumb, wrong, and retweeted by others in a way that made his late deletion of the remarks too little, too late, but the statement accused us of illegal acts, which is a serious issue.

That said, winning the case would be costly and take a long time, something Wayland understood full well. They were gambling that we’d go away and save them an embarrassing apology.

We went another way. We figured, instead, we’d do the charitable thing and do for Wayland what we do for our clients and instead amplify their activities and actions. If they did a great job running their business, our coverage would be a win for them. But if they didn’t, we’d make sure everyone knew about it, and that would cost them a lot more than an apology.

The story that follows is, in our minds, an unbiased, fair, well-sourced, complete examination of The Wayland Group and how it does business. It’s also very conflicted, for the reasons outlined above.

If you choose to believe we’ve written this story because of a grudge (fair), or because we short sell the company (we don’t short), or that we would never give any credit to Ward because of his past behaviour (we begrudgingly would, if it were merited), that’s understandable and fair.

To counter that, we went to some of the most successful people in the cannabis industry and asked them what their process is to find foreign assets, value them, do the proper due diligence on them, and properly fit them into their existing operations, so readers can compare fully what Wayland is doing against fair measures of quality.

To be sure, that’s a lot deeper a dig than we normally do, but we want to be seen as fair and accurate, not just a short report tossed out into the market like a stick of dynamite.

If you disbelieve what we’ve researched here, okay. If you’re planning to put your money into the Wayland Group and don’t care what we say, that’s fine. The one thing we’d ask is, rather than dismissing the following, read what we and others have said, check the sourcing provided, and come to your own conclusions.

In short, protect your neck.

By all means, prove us wrong. Find something we missed. Start your own investigation.

At the outset, we set this assignment to our writing team in the following way:

- Go deep as possible, even if it takes a while, even if trolls on Twitter are impatient

- Cover your ass legally by ensuring everything is adequately sourced and correct, because they’ll probably sue if we give them reason

- If the company is doing the right thing, give credit where it’s due, because that’s what journalism demands

This is the Wayland story.

THE BUSINESS MODEL:

Wayland boasts they are an international cannabis company with operations in Canada, throughout Europe and, pending the approval of previously announced transactions, more interests in Australia and Latin America. Those are their words.

That’s actually a business model we like, because diversity can be a nice buffer in a sector where governments legalize – and de-legalize – with impunity. As we’ve seen in places like Oregon, a well-meaning regulator can accidentally set the local industry back years while trying to do the opposite, so a hedge makes sense.

Germany places limits on how much product can be produced? Run your European operations through Malta instead. Government of Malta is dragging its feet on rule changes? Hey, Colombia is still growing, and Australia is coming, and Denmark has a system, and Lesotho has licenses. There’s a whole world of opportunity out there.

Diversity is what made Origin House such an attractive company to tens of thousands of investors and, ultimately, an acquirer. Canopy Growth Corp has so much foreign diversity that it can be tough keeping track. Aurora (ACB.T) and Aphria (APHA.T) are doing business in Germany and have eyes on Africa and Europe and Australia.

So Wayland is in the right place if it’s looking to foreign shores for opportunities.

But there are also issues with that strategy.

- It’s notoriously hard to do well. The moment you operate in other countries, you’re dealing with evolving laws in multiple jurisdictions, trusting local partners to do business in the same ethical and legal manner you would, finding the cash to get those assets built out, and then plugging those assets into your global network in a way that complements rather than bottlenecks your core operations.

- When is an asset not an asset? You and I can set up a numbered company in Tirana tomorrow to focus on the burgeoning Albanian weed market, and we could even submit an application to get a license one day, should there ever be such a thing, but most people would struggle to call that set-up an ‘asset’, compared to actual facilities and licenses in countries where business is permitted.

Companies at the largest end of the Canadian value spectrum, like Canopy, Aphria, and Aurora, have embraced global expansion, and been dicked around by it.

Recently, Aphria’s international purchases came under the microscope by short sellers, and were ultimately found wanting. The shorters suggested the assets were largely not real, sold to the company by other companies Aphria execs had a financial stake in, and had been flipped in mere weeks for multiples in price.

Aside from the wasted treasury, that situation cost the company billions in market cap, a CEO, and legal threats. They’re still dealing with the PR nightmare and having to pump millions of dollars into making those assets legit.

When Wayland boasts of assets in Argentina, the UK, Italy, Malta, Australia and more, the impression they give is one of a jet-setting team flying experts around the world and building real businesses in places where the opportunity is massive. The problem comes when one looks deeper into it and finds many of those assets were not companies just weeks or months before Wayland bought them, and appear to be an individual or individuals who have no assets to speak of.

I asked Supreme Cannabis (FIRE.T) president John Fowler if there would ever be a point where his company would buy another company that was just a few months old and had no license.

“No,” was his curt reply. “We’d need to have seen them in action for some time and know they were a true team of professionals, that there were assets and advantages to doing business with them.”

I asked Cam Battley of Aurora the same question.

“One guy with a license application? No. We can do that ourselves,” he replied.

Danny Brody of Green Organic Dutchman (TGOD.T): “We’re not averse to doing a joint venture with a small operator, but we’d want to know how much money they’re putting in alongside us. JV is the keyword. We’re not going to buy someone else’s business plan.”

DOING IT WELL:

Last year, Supreme bought 10% of a Lesotho-based licensee, Medigrow, and spent nearly a year in due diligence, ensuring the company in question had real assets and a professional team and would ultimately be able to supply Supreme with product that met its standards. Central to the deal for Fowler was a social responsibility aspect that will see hundreds of employees raising the standard of living for thousands of extended family.

Medigrow was the first licensee in Lesotho, and was granted the right to grow a year before any other licensee. Currently, they are 33 licensees in the country now, but most can’t afford the $37k license fee required to actually start growing.

“As with many potential transactions, Medigrow was introduced to us by someone close,” Fowler said. “We met their leadership team, were impressed by them, and after going back and forth multiple times, we sent our team down there to visit and determine not just that the facility and license were real, but also to be sure this was a facility that could deliver a long term competitive advantage…We needed to physically see that management team in their element, and that took multiple trips to Lesotho as well as their guys coming to us in Canada to see our facilities over a number of months.”

“Once we move into a market,” he says, “we’re not going to be embarrassed. We need them to operate not just in accordance with local regulations, but to be on that path to market leader. They represent us.”

That’s fleshed out online, where Supreme features the Medigrow Lesotho brand on their website. You can also see details on the Medigrow website.

But building your own website is cheap. When third parties echo what you say you’re doing, then you’re talking about something serious.

As you can see on this page put out by Medigrow’s construction partners, that shows some beautiful imagery and intensive detail about what they’re building, this is a very real project.

Medigrow’s Twitter feed has a load of images from the facility, and detail about their social impact, and is certainly not the work of an intern.

Then there’s the local media reports.

In an interview with Lesotho Times this week, chief executive Andre Bothma said a lot of work has already been laid down with over $250 million already spent on the project.

“We have already installed the critical infrastructure, water, electricity, tunnels, acquisition of essential expertise and employment of 300 people to date,” Mr Bothma said.

He said their staff compliment includes people with high-end science skills like biochemistry, agricultural sciences and pharmacists among others. While the majority of licence holders are yet to make any movement, Medigrow is already miles ahead and Mr Bothma attributes their achievements to sheer determination.

If that’s not enough for you, here’s some video:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=9G-na6DMykk

We can all be in agreement that there’s a real company there, which is what investors need to know before placing their bets.

In contrast, if one looks at the Wayland Group website, you don’t find images and videos and evidence of a lot of international business being done.

Rather, you find an almost complete absence of such detail.

You don’t find current investor decks (the most recent posted is from 2017). You don’t find complete and audited financials (December 2018 financials are late, and might not show up until June of this year). You don’t find a burgeoning online store (there’s no link from their site for a place to buy their products), or fantastic brands (many of their brands point to websites with a logo and nothing else) and there are no pages devoted to their international assets (they’re not even listed on the site).

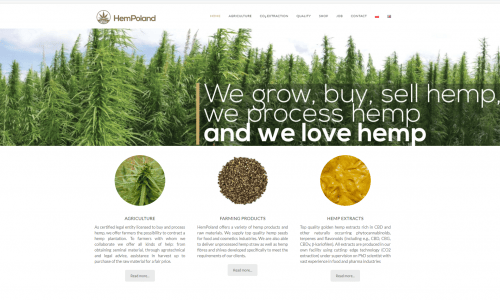

By contrast, when I look at Wayland competitor The Green Organic Dutchman, which recently bought a hemp farm in Poland, I have no trouble finding information about what they bought.

If I click through to HemPoland’s website, there’s a lot more information describing what they do and how they do it.

Heck, if I want to, I can go to that company’s shop and buy products from the European sites that stock them.

If I look at the TGOD financials, I can even see the breakdown of what HemPoland cost them to buy, and what it brought in revenue-wise on the back of that:

- Completed the acquisition of HemPoland on Oct. 1, 2018, for total cash and deferred consideration of approximately $18.6-million;

- Announced its first quarterly revenues through HemPoland resulting in $1.9-million of revenue for the fourth quarter;

I know TGOD comms boss Danny Brody pretty well, so I called him up to figure out what his team’s process is to acquire a foreign asset.

As expected, it’s pretty in depth:

“For HemPoland, we had a team from our company checking everything they do, everything they claimed, whether they have products on shelves, are they doing what they say they are, with actual revenue?”, he said.

“After our team has had a look, we then send a team out from one of the big accounting firms to do their own due diligence and go through their accounting to verify everything for our own auditability and traceability. We actually did that deal on a multiple to earnings basis that’s on the low end, with performance based incentives giving them upside. There are a lot of deals in the cannabis space with guys running around with licenses and nice Powerpoints and getting umpteen millions for a valuation, but we refuse to do that. HemPoland had a real business, and that’s what we paid for.”

I asked about what the valuation for TGOD might be for an individual or individuals in a country that are looking to establish a business and ‘might be a good local person to stick handle that,’ and the answer was quick:

“Zero. Like, literally zero.”

“The deal we did with a group in Mexico, let’s take that as an example. We’re setting up a business there and they’ll be our importing and distribution arm, their team is well connected in the Latin American regulatory space and pharmaceuticals space, they’re a real group with established business connections, but that JV starts at zero.”

Meaning?

“We each put in money to get things going.”

For TGOD, you’re either being acquired because there’s an actual business been established and work being done, or you’re a local partner with a prospect of doing business eventually, but you bring your own money and assets into the deal to show you’re a pro.

“If there’s nothing more than a license application and a powerpoint deck, we’re not cutting you a cheque because we could go do that ourselves,” says Brody.

The acquisition in Poland showed TGOD paying $20 million for a run-rate of $8 million, which is right in line with how you might price a deal in any other industry. No ‘weed markup,’ no middleman tossing an extra digit into the sale price and no deals closing after a week of phone calls.

Here’s what it looks like on Google Street View:

“We have no prob paying up for value and partnering with the right people,” Brody said. “In Denmark, we’re helping set up a company with an ops group that’s been in the business for 80 years and has strong bench strength in genetics, and they’ll run operations for us. Our intention is to work with them to run operations for us elsewhere in Europe going forward, so that’s a value add, especially when everyone’s strained for bandwidth. We’ll do that deal, but we set up with them from that place of zero, as partners. They put money in and we contributed evenly, we didn’t pay up for the privilege of doing business with them.”

Those deals generally don’t close quickly, even when there’s a bit of a gold rush afoot to get into a country that might move quickly to legalization.

“HemPoland took us a year to get closed, literally, and we’re so active in their business and involved in their operation, it’s not even funny. We’re back and forth constantly. People underestimate how hard it is to integrate a business into your existing company. Frankly, if you’re grabbing 16 in a year, that doesn’t work. Our Jamaica deal, that took about a year, and we were working hard for all of it.”

Cam Battley at Aurora Cannabis said he agrees.

“We acquired [German company] Padanios in spring of 2017, it was a $23 million acquisition for the largest distributor of medical cannabis in Germany and Europe,” he says. “At the time, they were moving Peace Naturals and Bedrocan product only, and in tiny volume compared to today, but they were extremely professional, former management consultants with McKinsey, and they really knew the business. They gave us great confidence that we could do business with them in the right way. We weren’t just acquiring a distributor, we were getting into a deal with retail positioning where we got full pharmacy price for product, rather than just wholesale, so instead of receiving $7-8 per gram, we were getting $12-15.”

Battley recognizes that, at the time, that deal seemed pricey.

“What made us want to go ahead with that was they had that network across Europe which has helped us get into a lot of European jurisdictions, because they are all different, sometimes very different, places to do business. You really need a top notch team that understands the regulatory processes and bureaucratic processes, in addition to having the product. Those don’t come around often.”

One of the things Aurora is focused on with their acquisitions is the potential for damage; that is, ‘Will this come back to bite us on the ass?’

Marc Lustig founded CannaRoyalty, now Origin House (OH.C) and built it into, at one time, a 25+ asset cannabis aggregator in just a handful of years. He knows a thing or two about running the rule over a potential acquisition. His take on the worth of an asset is simple:

“When someone says to me, ‘I’ve got a guy’? I have no interest in your guy.”

THE WRONG WAY:

Wayland appears to have a different way of sizing up their deals for foreign assets.

For example, in Argentina, where Wayland acquired it’s most recent asset, the government there has explicitly stated there will be no private licenses allocated. All marijuana will be sold by the government, and given away for free.

Wayland didn’t let that prevent them doing a deal anyway.

ARGENTINA:

Wayland entered into an agreement to purchase 819 hectares of existing developed agricultural land in the San Juan province of Argentina in December 2018 from Agro Ivica Dumandzic, which was owned by a company called Ta Blu Holdings, incorporated in Bermuda, of which Steven Snelgrove and Doug Keevil are principal executives. A Brian Miller is also mentioned in the filings. Wayland paid USD$4.5M in cash and $4M in shares for the property.

“The properly [sic] has existing mass-scale irrigation, using runoff from the Andes Mountains, and produces one million kilograms of wine juice and 400,000 kilograms of olives per year. Existing on-site agronomists and farmers will take their knowledge of horticulture and apply it to Wayland’s existing world-class system of cannabis cultivation. Outdoor cultivation will take place in existing alfalfa fields to supply Wayland with low-cost inputs. Initial extraction will take place in Argentina.”

Yes, they bought an alfalfa farm.

If you go searching for the names of the people they bought that property from, the only mention you’ll find is of a Steven Snelgrove who was a stock promoter back in the 1980’s, and whose only online trace these days is in the pages of books about stock promotion.

But where the Argentine assets came from isn’t as important as what they are. The assets are described by Wayland as a candidate for “the first Argentine federal medical cannabis licence, approval expected in early 2019, and existing supply agreements for CBD products.”

It’s early 2019, and not only are there no Argentine federal medical cannabis licenses for private company production yet, but there won’t be any time soon. In fact, the government plans to grow it through its own agencies, and give it away free to patients.

The new legislation restricts cultivation to government agencies – The National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) and the National Institute of Agricultural Technology (INTA) – thus denying private citizens with health problems the right to grow their own cannabis. [… ] Currently, cultivation for personal use can garner a prison sentence of up to two years, while commercial cultivation is punishable by between four and 15 years imprisonment.

That passage was from a report in 2017, so one could argue it’s outdated.

But it’s not. This from an International Drug Consortium briefing paper published last month:

In Argentina, meanwhile, a norm was issued that allows patients to import their medication while the state initiates the local production of pharmaceuticals for the domestic market.

From Marijuana Business Daily in February, barely a month after Wayland supposedly acquired its candidate for the ‘first Argentine federal medical cannabis licence’:

Once the new [Argentina] program is up and running, registered patients will have access to medical cannabis free of charge. There’s currently no domestic supply and imports have not been authorized for the nascent MMJ program.

I want to be charitable here but, from what we can find, Wayland has bought an olive and alfalfa farm and called it a ‘candidate for a cannabis license’ in a country not handing out cannabis licenses to any company.

If we’re being charitable, Wayland execs are completely ignorant to what they bought. If we’re being less charitable, they bought this property knowing it has no chance of getting a cannabis production license in early 2019, or even 2020, and did so just to convince investors they were more global than they are. You can decide which is more likely.

Then again, even if this property was the one that God himself would bless with licenses and great wealth and unicorn poop fertilizer, Wayland values the asset so highly they flipped half of it, and their other international assets acquired around the same time, for stock in another company with a lower market cap, just months after buying it.

The Argentina deal is, in our opinion, worth no more than the value of the real estate, perhaps more if you fancy selling grape juice for a living, which actually sounds okay if we think about it but certainly isn’t core to Wayland’s mission.

If you think Wayland got hooped in Argentina, just wait ’til you read about their Maltese adventure.

MALTA:

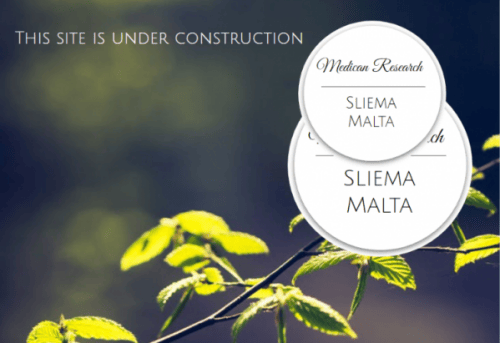

The most notable thing about Wayland’s Malta deal is how utterly worthless it was even as Wayland was trying to pay $10 million for it.

Here’s the company announcing the deal:

Maricann is pleased to announce that it has entered into a non-binding LOI to acquire 100% of the issued and outstanding shares of Medican Holdings Ltd of the Republic of Malta. Medican Research Group, a subsidiary of Medican, is one of six companies approved to receive a license in Malta.

This license will give Maricann the ability to import, extract, manufacture finished dose products, and distribute cannabis for medical purposes within Malta and the European Union.

Pursuant to the terms of the letter of intent, if the transaction is completed, Maricann will pay USD$10.1MM comprised of USD$7.6MM in common shares with a deemed price of not less than $2.35, and USD$2.5MM in cash.

Amazing! Malta is a gateway to the European Union. If you’re into Malta with a real license, why, you could make millions importing and exporting.

One problem: The company Wayland was going to buy for US$10.1 million?

It was six weeks old. And not getting a license. At all.

Initially, Medican had received initial approval and Maricann received confirmation of the same. Malta Enterprise then contacted Maricann to request the Company make its own application, as their preference was to work through Maricann rather than Medican. The Company then submitted its own application to Malta Enterprise who have acknowledged receipt. Maricann anticipates the application to be reviewed within the next 30 days with a decision on the approval status.

The Wayland spin here is, ‘we’re so great, Malta wanted to cut out the middleman!’

Cool story, but not at all true, according to local news sources.

Here’s MaltaToday:

A Maltese start-up that attracted the interest of a Canadian medical producer for a $10 million deal for a letter of intent from Malta Enterprise, was rejected by the state investment arm.

Earlier last month, Canadian medical cannabis producer Maricann announced it was planning to acquire a Maltese start-up, Medican Holdings, for $10 million.

But the Maltese company was only formed in March 2018 and was then still not in possession of a letter of intent (LOI) from Malta Enterprise.

A government spokesperson this week told MaltaToday the project proposal submitted by the Medican had been rejected by the board of Malta Enterprise and that no LOI would be issued

Cast your mind back a few pages ago, where the leaders of the Canadian cannabis industry told you they’ll take a year to do their due diligence on these deals, where they’ll have those deals verified by multiple third parties, where they’ll fly out and see for themselves what they’re buying, check that it has what it says it has, and then they’ll load up their deals with incentives and milestones that must be hit for the operator to really make bank.In contrast, Wayland wanted to buy a six-week-old company with no license, that the government was so unimpressed with that it reached out to Wayland and said, ‘You sure you wanna go there, bruh?’

As we found, this is a pattern with Wayland Group.

As is the torturous web of shell companies that come packaged into most of their international deals.

Medican is owned by Cosign Swift Holdings and Resulting Channel Holdings, both registered in Malta. Cosign is in turn owned by Norwegian firms Lommeboken AS and Okamo AS, while Resulting Channel is owned by the experienced finance entrepreneur Lars Christian Beitnes, who has founded several financial services companies and chairs various listed companies.

A shell filled with shells.

By the way, here’s the website of the company they wanted to buy, complete with lorem ipsum placeholder text. When the company became aware we were investigating them, the site was suspended within a day.

So what does Wayland do when faced with this crisis?

Why, they just apply for their own license.

Which they reportedly achieved in quick time. A ‘license to manufacture finished dose cannabis’ (in other words, a processing license) came from Malta Enterprise a few months later, but it comes with requirements.

The company has received an initial allocation of 2,750 square metres of industrial space. The approval in Malta is conditional on a number of items, including: (i) operation of the business in compliance with applicable laws, (ii) compliance with certain reporting requirements, (iii) the company’s Maltese subsidiary reaching an employment level of at least 28 full-time equivalent employees within three years from the start of operations, (iv) the company’s Maltese subsidiary investing at least 9.5 million euros in improvements to the site, plant, machinery and equipment within three years from the allocation of the applicable site, and (v) the company obtaining a licence from the Medicines Authority.

The situation described in that passage has not changed in the year since Wayland announced it’s Maltese foray, at least according to public announcements. No announcements of staffing, or construction, or money invested.

In fact, while Wayland has bragged of having a license, their partners at ICC International (WRLD.U) revealed they actually don’t yet when they later announced they were taking their piece.

The Maltese license will be awarded by the Medicines Agency, and the LOI for a license was granted from Malta Enterprise, the country’s official economic development agency. The Maltese license will permit the Company to supply its Maltese operation with raw materials that will then undergo advanced post processing to create pure Cannabis distillates.

Canadian cannabis consultant Deepak Anand put it simply:

⚠️There are NO ‘Licensed’ #Cannabis Producers in Malta.This is 1 of 6 companies that has an LOI from the Government of Malta making them eligible to ‘apply’ for a license in Malta (when the government releases regulations and eventually applications)⚠️ https://t.co/uio4Lw0mb4

— ᴅᴇᴇᴘᴀᴋ ᴀɴᴀɴᴅ (@_deepakanand) May 17, 2018

To be fair, this isn’t a worthless asset. But if it was so easy to get an LOI from Malta Enterprise that Wayland achieved it in two months, why were they going to throw a whopping US$10 million at someone else for the same level of work?

Origin House’s Marc Lustig has little patience for ‘almost deals’ and sees them as a failure of due diligence.

“Our execution rate of deals that we were looking at was maybe one in fifty, as opposed to those we were working on. We never left any license acquisition or process to chance, never gambled on one coming sometime so that we can say to the market we have a license underway.”

One of the reasons for that is the need to steer clear of embarrassment and suspicion in an industry that is heavily regulated.

“When a company says, ‘it turns out we’re moving away from that, we’re putting it on hold, we’re evaluating strategic alternatives – all that – that’s an admission of failure.”

COLOMBIA:

At one point, there was a lot of interest from the public markets guys in getting weed licenses in Colombia.

From November of last year, The Grizzle had more:

In September, Aurora announced a $300 million deal to buy leading South American producer ICC, which holds Colombian production licenses. Aphria tied up a similar deal to buy LATAM Holdings and Canopy Growth Corp. bought Colombian Cannabis S.A.S for $96 million in July.

Wayland now takes the number of regulated Canadian cannabis producers operating in Colombia to at least eight, and the country is becoming a key battleground for the leading lights in the rapidly flourishing marijuana industry. It spent C$22 million ($16.7 million) to purchase Colma, valuing it at C$2.00 per share.

You know what? We don’t hate this.

There’s more in the Wayland MD&A that, if the numbers are right and current and not projections, makes this a decent sounding deal.

It is anticipated that following the completion of the acquisition that the Company will cultivate THC cannabis outdoor and year round with an infrastructure investment including 415,000 sq. ft. (38,554 sq. m) of processing and clone and vegetation greenhouse facilities to support outdoor cannabis flower production of 125 hectares.

It is expected that a minimum of two full harvests will be achieved per year operating in an ideal climate. The current plan is for initial crude extraction to be completed in Colombia and exported for further distillation in the Company’s global Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) facilities in Germany.

Okay. I see you, Wayland. Fair play.

Colombia is hot, in that a lot of other Canadian companies are there, and here Wayland actually shows exactly how this asset plugs into other things they have.

You want that from a company with assets scattered around the globe. There’s no point having ten things in ten countries repeating work and costs, you want them to plug and play.

Added to which, with four licenses, according to Wayland, there’s evidence of short term value, be it in the work done to get those licenses, if not the development that it appears has followed.

We’ll have to take Wayland’s word on that because, though we can’t find any evidence of progress online, nor of a Colma web presence, there’s been relative ease and a lack of expense involved in getting Colombian licenses by others thus far.

When we dig into who owned the company being rolled into Wayland, we find a Colombian entrepreneur took home $3.5 million on the deal, a branding company called Lirios De Los Valles Corp enjoyed a bit over $2 million, another $2 million went to a company called RG5 Investments, which is owned by a dispensary operator out of Illinois named Gorgi Naumovski, and lastly there’s a million bucks going to a guy named Robert Kennedy, who I’m not even going to bother trying to track down because his namesake has the first million pages of search results on Google.

It’s worth noting that those amounts are now vastly smaller, what with the collapse in Wayland share price.

But you know who made most of the money on the deal, pulling in a whopping $12 million+? That’s a company called Viriditas Capital Ltd, which is run by a Toronto lawyer now based in the UAE named Craig Bridgman.

From what I could dig up, Bridgman reportedly runs the Barbados-registered Cambridge Capital, co-founded Alberta-based Captus Partners, and is a former in-house counsel to Sprott Asset Management, as well as being on the board of several resource companies with projects in Africa.

The way this usually works is, local starts a business, gets themselves that license, Canadian lawyer gives them what they want to hand it over, takes it to an LP and slips it for 10x what he spent. It would appear likely this is what happened here, and we assume this because, well, it’s what Bridgman appears to be doing with many of Wayland’s foreign assets.

Such as the one in the UK.

UNITED KINGDOM:

Wayland’s UK assets are less difficult to make sense of, based on publicly available information, because unlike Colombia, they appear to us to be almost completely fictional.

Wayland entered into an agreement to acquire 51% of Theros Pharma, what it called an “early stage company that has successfully imported cannabis to the UK for patients with a prescription for medical cannabis.”

“We’re proud to join with Theros on the journey to enhance lives through cannabis, now in the UK Theros’ dedicated team of professionals and advocates, who were instrumental in achieving cannabis legalization in the U.K., will work with Wayland to create access to cannabis for patients and further advocate for personalized medicine,” declared Wayland chief executive officer Ben Ward.

‘Dedicated team of professionals! Creating access to cannabis for patients!

This does sound promising. Until you overturn just the first rock.

The UK is a big potential market, and if Wayland found a local applicant that could be in that market early and profitably, then a deal is certainly worth considering, perhaps as a joint venture, but one of the first things you’d want to know is, does the person running the show even want cannabis to be fully legal?

When the deal was announced, Wayland agreed to pay Theros €3.8 million in WAYL stock at $1.65 p/share (it’s worth around half that today), with a promise for €24 million in stock more if/when the company gets a UK cannabis license.

We figured that was a little pricey, considering the company, which was officially called Professor Mike Barnes Ltd a week before Wayland bought it, has no facilities, no license to speak of, and may never actually get a license at all.

Professor Dr Michael Barnes, which is what they actually bought, is somewhat of a Marc Emery type in the UK, in that he’s a marijuana activist but also largely unliked, both in and out of government.

Weirdly, Barnes has taken a public stance that recreational marijuana use should be banned, which is certainly contrary to Wayland’s aims, and that stance hasn’t brought him love from the cannabis community.

On the government side, he has reportedly been barred from several committees aimed at deciding who may get cannabis licenses, or how that licensing may work, due to previously undisclosed corporate conflicts of interest… among other things.

It’s been reported Barnes had previously taken an advisory role with a group called CLEAR, headed by Peter Reynolds, a guy who could charitably be called a far right, anti-Semitic, homophobe, and which has seen Barnes struck off a lot of cocktail party invite lists.

But hey – scandalous associations or not, let’s be charitable and agree that paying to get access to a public figure like the good Doctor Professor who can, at least, be your local man on the ground while the licensing process is ongoing.

We can admit to that because others apparently felt the same way. Earlier in the year, before Wayland bought Barnes and renamed him to appear like he was a pharmaceutical company, another North American company put Barnes on the payroll as a consultant.

They got a better deal. They paid him $50k per year.

Wayland paid €3.8 million, which is an 85x markup, based on today’s exchange rate, and a 170x markup when you consider they only bought half of his company.

That’s tough to defend, considering Barnes’ company filed financials from mid-2018 showing total equity of €385k, down from €434k the previous year, pricing the Wayland offer at 18x equity in the short term and 144x equity should he ever get a license.

Even if you believe that’s a good deal for access to a local weed gadfly, you’d be hard-pressed to explain that value when you discover the amazing Dr Prof reportedly told the Daily Mail newspaper he has ‘given away‘ five sixths of his business to ‘other interested parties,’ keeping just a 15.9% stake for himself.

We’re not sure why Barnes would all but bail out of his company just before some Canadian giant came in with a fat chequebook, unless the middleman facilitating the arrangement made it a requirement of the deal that Barnes get lost.

The price tag seems even more bizarre considering it paid for a mere 51% stake in the company, and with half of that half interest now having been split off to ICC International, Wayland owns only 25% of the deal going forward.

What did Wayland get for their money?

As you may have noticed above, Theros was presented to investors by CEO Ben Ward as a company that has ‘imported cannabis previously,’ which is definitely true, though the sole importation in question was for a young epileptic child named Alfie Dingley, who had become a media story when his parents couldn’t obtain legal marijuana products to treat him.

Barnes helped get some weed into the country, which is no small thing for wee Alfie, but according to the purchase agreement, this wasn’t the start of something long term. In fact, it was most definitely and specifically a one-off:

There’s no Theros website – I mean, who’d have time to build one, considering it was one day old when Wayland purchased it – and the registered office of the company is, well, not overly industrial.

By any unbiased assessment, even if that lovely house is tossed in on the deal, half of Theros does not appear to be worth €3.8 million, let alone €24 million going forward.

Even more interesting is how the deal came about.

A day before Wayland announced it had bought Theros, the UK company filed documentation with regulators to show, just a week earlier, Professor Barnes was no longer a person with significant control‘ in the firm.

The person who replaced Barnes as the control person of Theros a week before Wayland jumped in, was – wait for it – Craig Bridgman, former Toronto lawyer, now housed in the UAE, who made the lion’s share of the Colma deal in Colombia a few weeks earlier.

While he’s clearly a canny markets guy, one thing Bridgman has little clear experience in is running a cannabis company, so there’s no value in the deal associated with his presence.

So much so that part of the deal Wayland did to buy his company was for him to get lost.

From the document filed at Sedar outlining the deal, among the things the seller needed to supply to Wayland was:

3.1.1.5 A statement from Craig Bridgman confirming for the purposes of section 790M(9) of the companies Act 2006 that he has ceased to be a registrable person within the meaning of section 790C of the Companies Act 2006 in relation to the company.

Though Bridgman pulled off two fat weed deals, to the same LP, within days of one another, it’s safe to say he brings zero value to the deal.

Taking his place: Wayland CEO Ben Ward, with Dr Professor Barnes, and Robert Reid being listed as B directors.

Remember the name Robert Reid. He’ll be important later.

Going by timelines, the Theros deal appears to have played out like this:

- January 2018 – : Barnes starts receiving a monthly consulting fee by a Canadian firm

- October 22, 2018: Barnes hands over control of his company to Bridgman and others, for an unknown amount

- October 22, 2018: Company changes its name from the clearly one-person brand of Professor Mike Barnes Ltd to the much more impressive sounding Theros Pharma

- October 26, 2018: Wayland announces it is buying Theros for many millions, citing the “dedicated team of professionals and advocates” that come with it

- October 27, 2018: Theros files the paperwork alerting UK regulators of the earlier ownership- and name-change of the company

- January 15, 2019: Wayland announces it is selling half share in its international assets, including Theros, to ICC International, in an all-share deal

A cynic may suggest it’s almost as if someone identified a minor foreign asset that could be passed off as a bigger asset and sold it to a lawyer to beef it up, who then sold it on to a complicit LP that might realize a big market cap pop on the overpriced deal, which then continued the parlay by announcing a flip to another company looking for the same market cap pop, with everyone being paid largely in stock and overlooking the fact that there’s no actual business being done in the company being flipped.

I mean, it almost sounds like one of those deals Aphria got caught making earlier in the year, when they overpaid for way early stage assets sold to them by one of their founders, Andy Defrancesco, with Aphria execs personally enriching themselves as part of the arrangement.

You know why it sounds like that?

Because it fuckin’ is.

From the Daily Mail:

Since January [2018, Barnes] had earned a ‘modest monthly consultancy fee’ from SOL Global, totaling about £50,000 a year.

Yes, Barnes had been on the payroll of North American weed company aggregator SOL Global all along.

And who is the chairman of SOL Global? Why, that’d be Andy Defrancesco, the guy infamous for having sold Aphria a bunch of international assets for jacked up prices, just days after buying them himself on the ultra-cheap.

When the details of those deals were revealed, by short sellers with blood in their teeth, a massive drop in Aphria’s share price devastated investors, and when an independent Aphria committee investigated, they found, indeed, the assets were priced ‘on the high side’ and that execs at their company were potentially inappropriately enriching themselves through those deals.

So a Defrancesco connection is notable here. But how notable exactly?

We found, between the day when Barnes became a minor shareholder in his company and the week later when the WAYL deal for Theros was announced, there were suddenly a lot more people involved in Professor Mike Barnes Ltd.

The list, featured on WAYL’s Form 9 documentation confirming which people received shares in the deal, included a thick roster of names that all connect back to Defrancesco.

Suddenly:

- Bridgman owned 30% of Barnes’ company

- Robert Reid, CEO of Defrancesco’s SOL Global, now owned 15.9% of Barnes’ shares

- Anthony Vella’s (AKA Antonino Vella) 2443904 Ontario Inc, who you may recall as being a part of the Aphria board when Defrancesco was a founding investor, snared 6%

- NG Bahamas Ltd (Rockstar Kids Trust), which is a Bahamas-based trust for Defrancesco’s ex-wife and children, took a quarter of the deal

- Hill Street Investments Ltd, a group that includes Barnes as a shareholder, among five others, took another 3.6%

- And SOL Global Investments itself took a 3% nibble

Let’s be clear: There’s nothing illegal in buying something at a cheap price and selling it at an expensive markup. That’s just good business.

But if that’s happening, it means the guy on the other end of the deal is doing terrible business.

THE DEFRANCESCO DEALS:

‘Defrancesco’ has become somewhat of a verb in the last year, largely on the back of the Aphria deal but also because he tends to be tied up in a lot of shell movements that pick up scraps of cannabis deals.

He’s had a lot of success – he helped get Aphria started back in the day, SOL is no slouch, and Liberty Health has some worth.

But when folks hear “That’s a Defrancesco deal” they translate that as ‘it’s a cheap ass piece of bullshit that someone will get scammed into buying.’

So I called him, a few hours before this piece would be posted, and asked him about what he does. In a two hour, mostly off the record interview, he was very revealing about a lot of the cannabis business’ dirty little secrets.

On Theros, he didn’t deny that there’s nothing physically there.

“There’s Barnes, he’s not nothing, he’s actually been a very important figure in the evolution of cannabis laws in the UK, but there’s no building or license.”

“Barnes was the guy who helped design what the laws would look like back in like 2007, and was tasked with picking the seven or eight companies that would get a license in the UK,” he said. “Wayland was one of those companies. But the government changed how it wanted to do things and everything got thrown backwards.”

Part of why Barnes’ list was dumped was, he was being paid by Defrancesco at the time he made it, which put him in a conflict. Barnes is no longer part of the process.

“He’s still a really smart guy,” says Defrancesco. “He’s doing research, but he’s also made some enemies.”

On his deals, Defrancesco says they’re not ‘bullshit deals’, as I characterize them. He says they’re early, and that, frequently, whoever buys them decides to overhype them as being bigger and later stage than they are.

“I’m the guy who goes in before there’s a license process and works with the government and the health ministry and the agriculture guys, I find local people who know what they’re doing and can contribute, I lobby, I get lawyers and accountants, sometimes I’ve had to deal with the military, and that costs me money. I do the work, I spend the time, and at some point it needs to be passed on to an actual LP.”

To support this Defrancesco supplied me with an image of a building he’s constructing in Brazil before a license has been allocated.

“If I make a profit on that, that’s good business. If they want it fast, there’s a price to that. If it turns out great, the CEO takes the credit. But when they fuck it up, then everyone looks at me and says, ‘that’s a Defrancesco deal.'”

I don’t disagree with him on this. To be sure, nobody is going to suggest Andy Defrancesco has never cut a corner, or sold a company something they didn’t understand fully at signing, or rejoiced a deal on Twitter in a way that doesn’t look proper.

“I’m an idiot sometimes on Twitter,” he says. “But look, when you saw me in that Mexican pharmacy celebrating the pharmaceutical import/export company I bought, that I sold to Aphria, it actually was an import/export company. The fact that it owned a pharmacy wasn’t important, that pharma company was necessary to complete another deal in South America that required a federally issued import/export license to be able to export to that country.”

The devil, as always, is in the details. Defrancesco says he doesn’t know who Craig Bridgman, the biggest shareholder in Theros at the time of the deal, is. He concedes our timeline, with he and his people getting into the company days before Wayland bought it, is correct.

Currently, Theros Pharma does no business.

OUR CONCLUSION:

We believe Wayland’s UK asset has little to no worth, that Theros is not likely to receive a UK license, that Barnes has limited involvement in the company itself, and that between Bridgman, Reid, Defrancesco, and the others named, Barnes willingly let go of controlling interest in his company to the individuals named because he knew the much larger WAYL deal was coming through those individuals if he did.

We also believe ICC International knows the UK asset is of little worth. They list the company on their website as an asset but offer no more information than what is found in the news release announcing Wayland’s initial purchase, and certainly don’t mention any actual assets, licenses, pictures or documentation showing a license application is afoot or some sort of building is being built.

We should point out, that while doing bad business and overpaying for assets is not illegal, knowingly doing so, and telling investors that what you bought was actually amazing, could be considered fraudulent. At the least, it would be considered conduct unbecoming of a public company executive.

It’s not our job to pass judgment on whether that’s the case here or not, because we’re not shareholders of the company, nor shorters of the company, nor regulators of the public markets or class action lawyers.

This may well have simply been an example of incompetent executive oversight, perhaps a desperate attempt to grab at what quickly turned out to be a largely worthless UK asset, at a premium, before anyone else could get a foothold in that market, only to realize their error too late.

You know, just like happened in Malta. And Argentina.

It may well not be a deliberate misrepresentation of the asset.

But it would appear the asset has been misrepresented.

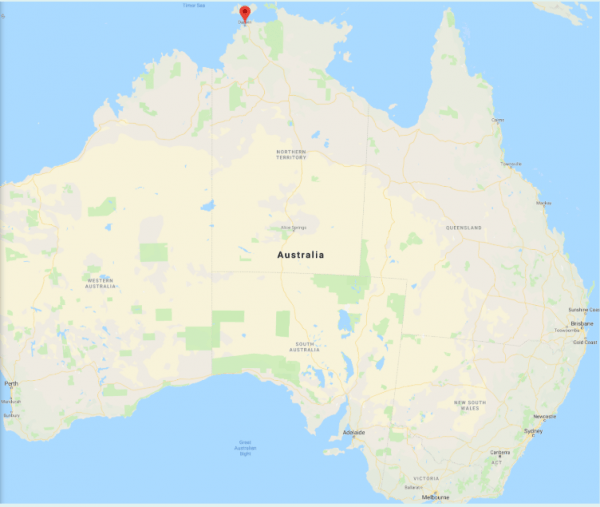

AUSTRALIA:

If the price that must be paid to have a third party in another country apply for a marijuana license for you within that country is around $5 million, and $25 million or so more when a license actually shows up, then Wayland’s deal for their Australian asset follows a well-worn path.

They must feel that’s the case, because the aussie deal is a carbon copy of the UK package, right down to who they did the deal with, how much they paid and, frankly, what they got.

Pursuant to the terms of the agreement, the company has agreed to make an initial payment of $4.8-million followed by a second payment of $24-million following certain milestones being achieved, including issuance to Tropicann of a licence to cultivate cannabis in Australia. Both payments will be satisfied by the issuance of common shares of the company based on then-current market prices, but subject to a floor issue price of $1.65 per common share.

Central to the deal locally is the Canaris family, who are well connected business folk in the Northern Territory and well connected to the local government.

You could do worse.

Australians generally like it when foreigners show up to flash some cash about. I know this because, as a natural born Australian, my countrymen lose their minds if a C-list actress does the 20 hour trip and tells them the weather’s nice. If the woman who played Ginger on The West Wing decided to travel to Sydney for a few weeks of sunshine, she’d be on every morning news show.

So when a big rich Canadian company showed up in Darwin to support Darwinian industry, it wasn’t unnoticed, and local government got right behind things.

Here’s how the Wayland deal was reported locally:

Wayland’s vice-president of communications, Graham Farrell, said the company felt the NT could become “one of the world’s largest cannabis cultivation areas globally”. He said Wayland would look to grow the crop outdoors, and several parcels of land in the Top End had already been identified.

Mr Farrell said, if all went to plan, the company envisaged building “a very large operation producing hundreds of thousands of kilograms of cannabis for multiple markets”.

There’s a lot to unpack here, mostly around how little there is to unpack here. Because, once again, Wayland appears to have bought themselves local consultants, the idea that there might be a license some day, and a lot of fresh air.

From what I can find, which isn’t much because the assets don’t really appear on Wayland’s website, and they have barely any information listed on ICC’s site, and they have no web presence of their own in any way, shape, or form, WAYL bought themselves a company that – once again – hadn’t existed a few months earlier, has no assets to speak of, and was certainly years of time and a large capital investment away from ever bothering the world with revenues… in return for nearly $5 million in WAYL stock.

Let’s be clear, and charitable – Australia is a a fine market for cannabis, with a young, growing population, lots of space to grow things, and a citizenry that has long had little trouble acquiring the means of getting stoned. While the government has dragged its feet on cannabis legalization, it’s definitely getting there, so forming a beachhead in the southern hemisphere is a smart move for any North American firm. And many have done so.

But it’s early.

According to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), which is handling the application process for medicinal patients, by the end of last year, there were 2,800 patients with prescriptions to buy product. Those numbers are small, but admittedly multiplying, even though only 58 doctors in the country are licensed to prescribe cannabis at the last count I could find.

There’s no question the current levels of permitted use will be dwarfed by the eventual recreational use boom, should the Office of Drug Control – and Parliament – ever get their act together and actually allow it.

NSW is also attracting investment, with ASX-listed Elixinol Global Limited making a $7 million application for a cannabis farm earlier this month.

In Queensland, international business Asterion Cannabis is trying to set up a $10 million growing facility on the outskirts of Toowoomba.

There’s money moving into Australian weed, but licensing is hard, as it was in Canada back in 2015:

[Consultant Adam] Miller says he’s worked with companies who have had to wait for over a ear to receive approval for growing facilities, which has stifled early growth in the industry.

“We’re still a few years off from seeing a fully operational and systemised medicinal cannabis industry in Australia,” he says.

That sure sounds like Canada in 2015.

So what did Wayland buy up in Darwin?

On Dec. 3, 2018, Wayland announced it was entering into an agreement to acquire 50.1% of Tropicann Pty Ltd, a privately owned Australian company located in Darwin as a way of targeting the Aia-Pacific market.

“The Northern Territory is the ideal location for our new Asia-Pacific hub. The location provides Wayland with ideal climate conditions in a globally respected and sovereign country with a large and fast emerging market of over 250MM people just 4 hours north.”

This statement baffles the hell out of me. A potential market of 250 million people? Is Wayland talking about selling weed to the island nation of Indonesia, with a population of roughly 256 million, and which has some of the strictest drug laws in Asia?

Indonesia’s cannabis laws don’t permit the production, possession, distribution, or sale of cannabis. Encouraged by Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte and his brutal efforts to fight his country’s illicit drug problem, Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo—also known as Jokowi—has publicized plans to lift a moratorium on the death penalty for drugs.

Under those plans, authorities would be granted the power to shoot drug dealers and traffickers on sight. But those plans have yet to be put into action.

People daring enough to buy or grow cannabis on Indonesian soil face serious risks if they get caught. Farmers who grow cannabis can face the death penalty or a minimum fine of 8 billion rupiah (equivalent to US $550,000) based on a 2009 law enforced by the National Narcotics Agency (BNN). The death sentence can be leveled on anyone found guilty of cultivating as few as five cannabis plants.

In nearby Singapore, possession of cannabis carries a sentence of 10 years imprisonment, and in 2016 a man was executed for cannabis possession.

Custom officers can request a drug test at the point of entry to #Singapore. If you test positive for drugs, you can be arrested and prosecuted, even if the drugs were consumed prior to your arrival in the country. https://t.co/abesNz8fQv

— travel.gc.ca (@TravelGoC) October 31, 2018

In 2018, nearby Malaysia, authorities recently executed one of its citizens for cannabis possession. While that country is indeed coming around on the topic of medical cannabis use, it’s a long way from ready.

A death sentence given to a young man selling cannabis oil to the ill has stirred debate in Muslim-majority Malaysia about its ultra-tough drug laws. The case has prompted calls for the country to become the first in Asia to legalise medical marijuana – but long-held stigma and a mostly conservative population means change could come slowly.

So it’s probably safe to say, if there’s value in Tropicann Pty Ltd., it’s not from the potential of catapulting cannabis products across the strait into the pharmacies and bars of Semarang, Surabaya, and Jakarta.

And if Asia isn’t where Tropicann is headed any time soon, it’s not headed anywhere because Darwin is a remote cowtown (quite literally) prone to cyclones, flies, hangovers, and filthy, oppressive heat. It’s the Alaska of Australia, a distant berg people flee to when bad life decisions have made living in the country’s southern cities impossible.

Put another way, it’s Northern Exposure, only with stifling heat, crocodiles, and wise old aboriginals in place of rain, moose, and wise old first nations folk.

Here’s the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) discussing all the reasons the Northern Territory, where Darwin lies, struggles on the agricultural front despite having a lot of area in which to make it work:

David Warriner, CEO of the Livestock Exporters Association Northern Territory, points out distance is a big factor: “Because the NT exports the majority of its product, almost everything has to be shipped 3000 kilometers south or is sent overseas, while everything brought in is manufactured in the south-east of the country and then shipped north. That puts a $200-$250 per tonne freighting cost on every single thing we use or consume in our business.”

Population size is a problem. There are 15 other Australian cities with bigger populations than Darwin’s, which, at 140,000, is about the same size as Coquitlam, BC.

Geography is also an issue. Imagine moving Coquitlam to Nunavut and you’d have some idea why supplying Australia with cannabis from Darwin makes little sense. There’s nothing around it for hundreds of miles, and major markets are thousands of miles away.

Variety of produce is also not the Northern Territory agricultural sector’s strong suit. As of 2015/16, the Northern Territory’s agribusiness sector was worth $736 million in sales, according to the ABC, of which 44% is based in the cattle industry.

That’s because growing almost anything else there is hard.

NT Farmers Association CEO Greg Owens:

When the English first came to Australia they tried to grow things like they did in England and they almost all starved to death […] It’s taken 200 years to work out growing systems for southern Australia, and they expect the tropics to do it overnight. It’s not that easy.”

Added to that, around 55 % of Northern Territory land is Aboriginal freehold land, which gets expensive the moment you change use on it.

Warriner says:

“Land tenure is a huge problem in that where you have pastoral leases, whether they’re perpetual leases or crown leases, the minute you want to change what you do it triggers native title […] The legal negotiations could be costly, he said, “and you have to effectively buy back the native title from the traditional owners. Which is fine but it also adds to the cost of doing business.”

Then there’s the weather.

Owens again:

“We’ve tried many times in the past to do dryland agriculture — growing crops without irrigation -and the rainfall in the north, while there might be heaps of it, is too unreliable in its timing and amount to rely on.”

But let’s be charitable and say they get all of this sorted out; the distance, the weather, the native issues, the red tape, and the Canaris family and friends actually get a plot of land to grow weed on from the state government – and the federal government okays them to do so.

Okay, cool.

The plan to grow outdoors in Australia has some merit – in fact, aussies have long grown weed outdoors in more southern climes, leading to an infamous ‘infestation’ of cannabis outside the Hunter Valley, where some 30 kilometers of weed was pulled by hand and burned by police back in the 60’s.

Australia is a decent place to grow weed. But you sure as hell don’t need to go to the hottest, most red-taped-ensnared, most remote part of the country to do it.

Location aside, there are positives in this project, but they’re people, not facilities.

Unlike their deal in the UK, Wayland’s Australian deal partners are no slouches when it comes to actually building things. They’re into a phosphate project in Katherine, NT, and an industrial salt project in Western Australia, so they’re not averse to new sectors, but real estate is where they do most of their business.

“Jalouise Pty Ltd (‘Jalouise’) is a specialist commercial property developer, investor and manager with over 25 years’ experience in developing and managing commercial properties for NT Government tenants.“

While they’ve built most of their fortune developing office towers in Darwin, the Canaris’ rent the vast majority of those out to state government departments which means, to be sure, they have sway in the halls of power – at least locally.

Our experience as Lessors for Government Departments

- Department of Justice and Attorney General

- Department of Corrections

- Department of Infrastructure, Planning and the Environment

- Department of Education Employment and Training

- Northern Territory Treasury

- Northern Territory Worksafe

- Department of Mines

So they’re fine upstanding local citizens. City fathers. Entrepreneurs of note. Wayland could definitely have worse partners to be their local agents.

So what do we know about the Tropicann deal specifics? We know it’s the Theros deal all over again.

There are no pictures to show, there’s no video to run, there’s no evidence of any actual business furthering a license application having been undertaken, but there is evidence the company they bought was – like Theros – only a few months old when Wayland bought it.

Hell, they even gave up shares for $1.65 each, just like in the UK deal.

We also know Tropicann had four shareholders when it was registered as a company on October 4, 2018. Those were John Canaris, Mike Canaris, Jeremy Edleman, and Skevos Macarounas. The same day they registered Tropicann, they also registered another company, Territory Hemp and Cannabis.

But when Tropicann was flipped to Wayland two months later, suddenly there were a lot more people involved in the deal and 51% of the shares in Tropicann were now held by Territory Hemp and Cannabis. The founding four now held reduced personal stakes (15%, 20%, 7.5% and 7.5% respectively), and a slew of new (well, not so new) names were now involved.

Of the new people involved, I bet you can guess who joined.

Craig ridgman turned up again with 16.67%, which is more than the Canaris family were left with independently to run their own company. Professor Michael Barnes suddenly owned 6.25%, which is odd considering he’s got no interests in Darwin, and the DeFrancesco clan are all in again: Robert Reid makes an appearance, as does NG Bahamas (Rockstar Kids Trust), and Anthony Vella’s 2443904 Ontario Inc. Stephen Murphy took a minor slice, notable only because of his involvement in the aforementioned Hill Street Investments Ltd, part of the Theros deal.

Defrancesco says a lot of due diligence was done on this deal with the principals and the local government, and that the deal was actually negotiated months before Wayland announced it, while conceding our timeline on the creation of the company a few months prior to the announcement.

THE PROGRAM:

What it looks like to me is, these guys have a particular kind deal in play.

In essence, if you feed an early weed property or application to Defrancesco that he can move forward, build up a little, and flip to an LP, he’ll not only get you a premium with that LP, and fast – he’ll bring you in on other deals moving forward.

If I’m being honest, that actually seems like a decent way to build a network of guys who’ll carry your water and shut the fuck up about the lack of specifics.

“That’s accurate,” he says. “We bring people into the family and they’re in subsequent deals.”

The shareholder end of this is, we’re invested in companies that, to save time and effort (and grab at something that might inflate a market cap), overpay for things they may not be able to progress, or integrate, or ever really use.

Marc Lustig makes no bones about how prevalent this is.

“I’d say it’s activity that has really picked up recently. We get offers from brokers, regulated dealers – and it’s scary. It’s not just promoters, it’s also the owners of the assets themselves, the amount of deals we’re being shown, that have no product, they’re without a building or a license, or it’s just a concept – three years ago we were seeing one a week, now we’re seeing two a day.”

I asked Brayden Sutton, CEO of 1933 Industries (TGIF.C), who had been there at the start of Supreme and has been a consultant in the weed space for many years ,what he does when he looks at a potential acquisition, and he found the question hard to answer.

“The truth is, almost everything you see is junk. I see so much crap out there and just think, we’re maybe a year or two from a lot of companies having to face a real reckoning with what they’ve bought. I’m not even looking at something unless you can see it’s a genuine business, and it usually isn’t.”

In the US, Andrew Glashow, CEO of Cannabis Life Sciences (CLSH.U), has avoided going on an expensive dispensary land grab, though companies that have done exactly that have driven higher market valuations than his own. The reason?

“It’s junk. Honestly, there’s so much junk. I was talking to one potential target recently and the opportunity suddenly dissolved because another company had paid the landlord of the place we were looking at $5 million to reserve it for later, in case that company ever gets permission to open one in that state. I mean, that’s insanity. I’m not going to name the company but most people could probably guess. It’s pretty sickening, and I think we’re going to have a wave of bankruptcies as this plays out.”

After Aphria was dug into and found wanting, losing their CEO in the process, other companies got the yips about their own questionable deals.

In quick succession, Namaste Technologies (N.V) ditched their own CEO for much the same issues as Aphria did, only to bring him back in an advisory role when he threatened to sue. They’re still shuttering international assets, having just announced in a corporate update that websites they run in several countries had to be closed to keep their bankers from freaking out.

Wayland, also, looked like it was getting nervous. Having just moved their general counsel into the President’s position, they recently changed auditors and lost some directors as their financial lateness dragged on.

None of those foreign subsidiaries have released any news to show progress since they were purchased, let alone revenue earned, and though Wayland has hyped the companies as being world leaders, in the few months since they acquired them, a half share in them was flipped to someone who has paid (in shares) even more on the high side than Wayland did, seemingly doing a similarly minute amount of DD in the process.