Burkina Faso is battered and bruised.

It’s been more than a century of political and economic strife for the tiny landlocked country which plays bullseye to West African nations Mali, Niger, Benin, Togo, Ghana and Ivory Coast.

Droughts, coups, regional fighting and colonial rule’s nasty legacy finally boiled into homegrown extremism with the recently emergent Ansar ul Islam (“AUI”).

Both AUI and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (“AQIM”) are attempting to turn the northern portion of Burkina Faso into a stronghold. It isn’t just them, there is evidence six other terrorist organizations are operating in the country, including Boko Haram.

Their combined violence has already hit the streets of Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou, most notably in January 2016 when terrorists laid siege to hotels and cafes in the city centre, leaving 28 dead and 56 injured.

A little over a year later, fighters attacked police posts, military installations and educational facilities outside the capital and away from its 2.2 million inhabitants, but city dwellers remain acutely aware of the activity.

After the attack in February, Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, Burkina Faso’s President, announced his https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistration planned to recall peacekeepers from both Sudan and Mali and redeploy them in the north to fight the growing terrorist threat.

Last month the UN Security Council adopted a French-led resolution for deployment of 5,000 military and police personnel to combat terrorists in the region, but it was never fully authorized because the U.S. raised a stink over member countries having to foot the bill for the newly-created force.

Will more boots on the ground drive out the terrorists?

In 2013, the French carried out an aggressive campaign against jihadists in Mali after they took advantage of civil unrest to control the country’s northern region. French generals believed they had driven out all the bad actors, but attacks continue, on both civilians and the Mali army as well as French and UN troops.

It seems every time the head is cut off the snake, as was the case with Bin Laden and Al Qaeda, the organization survives and another rises, such as Islamic State, which is even more radicalized than its predecessor.

Violent counter-terrorism is a last resort and a temporary measure until meaningful, long-term solutions can be found, otherwise, you’re just feeding the fire. You need to attack the problem at its source.

So, what are the roots of terrorism?

It isn’t the jihadist imams spouting their ridiculous vitriol while leading worship. Without the foot soldier and the suicide bomber and the thousands of nameless martyrs for the cause, Bin Laden would be talking to himself in a cave. The dangerous extremism, the one that spreads and blows up buildings with people inside, is fueled by desperation.

Despite Burkina Faso’s rapidly growing economy, a real winner against many of its African counterparts, it’s the 18th poorest country on the planet, and in 2015, it had a GDP per capita of US$613.04 compared to Canada where it was US$43,248.53.

Public education also lacks.

Twelve years after joining the Global Partnership for Education in 2003, Burkina Faso still had the 4th lowest literacy rate in the world with just 36% of the population able to read.

Then there’s food.

In 2015, it was reported that only 11.4% of Burkinabé children under the age of two received the recommended number of meals. Food insecurity was so bad the European Commission forecast 500,000 toddlers under the age of five would suffer from acute malnutrition that same year.

Malnutrition doesn’t just stunt the children’s growth, it stunts their education. According to the African Union Commission, stunted pupils, on average, finish less school than children with normal development. This further exacerbates the education problem and builds a vicious circle.

Food aside, life expectancy tops out at 57 for men and 59 for women in Burkina Faso. When you consider a 2009 study estimated there were 10 physicians per 100,000 Burkinabé, that fact isn’t too surprising.

That said, there is a beautiful vibrancy to the Burkinabé people. Ouagadougou is considered the cinematic centre of Africa with its biennial Festival panafricain du cinéma et de la télévision de Ouagadougou or FESPACO.

There is also a diverse sports community led by a love for football.

In fact, Burkina Faso hosted the Africa Cup of Nations in 1998.

Burkinabé come from a long line of survivors, they just need a hand up.

Gold miners in the region have a unique opportunity to help turn the tide on terrorism through enlightened corporate responsibility.

IAMGOLD (IMG.T) teamed with the Canadian Government back 2012 in a program that was meant to train 6,400 kids from 13 to 18 for a period of five years. The students would be given necessary job-skills to fit the demand of the region, even trades outside of mining.

The Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) bore most of the financial burden of the $7.6 million program, but IAMGOLD managed to put down $1.9 million. The CIDA is active in its pursuit of public-private development funding partnerships and has put more than $50.0 million into these international development initiatives since Harper’s conservatives implemented the program.

This style of development funding is commonplace in the U.S., but new territory for Canadians. As such, it has received its share of criticism at home.

Gold miners, when they reach the commercial production phase, can easily become multi-billion-dollar entities off a deposit if it’s good enough. Then why the hell can’t they fully fund a teensy multi-million-dollar community program? Which they provide as a matter of course to keep the locals from becoming “problematic.”

Fair enough. I suppose if you’re already a major, know the mine is a profitable “go”, maybe you should pony up the dough. However, juniors don’t have a lot of capital to play with and developing a property for production is a crapshoot, especially in the early stages.

Proponents, like Catherine Coumans, research coordinator at Mining Watch, an independent group based out of Ottawa, insist this is a win-win as it not only brings aid to the community, but also gives the miner a certain cachet with local officials.

This ties into the next argument made by classically-minded NGOs. Pooling international development money with corporate agendas tends to focus aid on very specific areas. For instance, the IAMGOLD program only directly benefited communities close to its mines.

NGOs claim this arbitrary and unfair distribution of aid slows development initiatives, and in some cases, undermines them.

Solid arguments, but when you see the desperation of many rural Burkinabé and the lack of options they possess, something is better than nothing.

But along that same vein, industrial gold miners in Burkina Faso need to focus their efforts on helping farmers grow more food, funding primary and secondary education, making training available for job skills outside of mining, and, believe it or not, assisting with reforestation.

IAMGOLD’s Essakane mine, located in the Sahel region of Burkina Faso, had an 8.2-year life in 2015 and unless the company can extend that with secondary discoveries on its 1,300-kilometre land package, it faces a challenge of not only bringing the local economy up-to-speed for mining but preparing locals for a life without Essakane – all in less than a decade.

So, we spent all this time talking about producers, what about explorers?

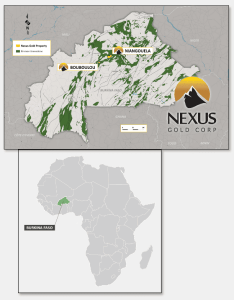

With US$2.5 billion in gold exports and lots more potential left in the ground, Burkina Faso is playing host to some shrewd juniors, like Nexus Gold (NXS.V).

With US$2.5 billion in gold exports and lots more potential left in the ground, Burkina Faso is playing host to some shrewd juniors, like Nexus Gold (NXS.V).

In fact, Nexus likes its stake so much, it just entered into a letter of intent (“LOI”) with BELEMYIDA SA, where Nexus will have the right to earn up to 100% interest in the Rakounga Gold Property, a 250-square kilometre holding contiguous to the company’s Bouboulou gold concession.

In the news release announcing the LOI, Nexus Gold President & CEO, Peter Berdusco, commented, “…This addition is important when you consider how this might influence the goal of establishing a resource at Bouboulou. There is significant artisanal activity in this new area which indicates gold mineralization continues along the established trends for some distance.”

He went on, “Our exploration programs will determine to what extent and obviously at what economic level, but we are excited at the potential value this strategic addition brings to the Company’s growing portfolio. We are looking forward to executing the definitive agreement in the coming weeks.”

Industrial mining corporations have a complex relationship with artisanal miners and in many cases, artisanal mining permits are superseded by industrial want.

Artisanal mining isn’t glorified in the eyes of Burkinabé. Many, except possibly the artisanal mine owners, would like the trade to be better regulated for a variety of legal, environmental and humane reasons.

When the majors eventually leave Burkina Faso, there will be no gold left to speak of. The families of artisanal miners who are temporarily displaced by industrial claims today won’t have anything for their kids to turn to when gold producers exit the country.

Therefore juniors, like Nexus, are striving to come to the bargaining table with comprehensive long-range views and effective programs to back up their community agreements.

Scorching the earth with military might may drive the terrorists into their bunkers and possibly kill their leader, but only food, knowledge and hope will halt the jihadists’ advance and heal Burkina Faso’s Sahel region.

Now, more than ever, gold miners, like Nexus Gold, have an amazing opportunity to protect their own assets against jihadists and help an emerging nation come into its own while leaving shareholders smiling.

–Gaalen Engen

http://twitter.com/gaalenengen

FULL DISCLOSURE: Nexus Gold is an EQUITY.GURU client.