When Vena Resources (name since changed to Forrester) was the on-the-button Toronto mover and shaker that it started out as, it was the kind of thing that smart, connected people put together in a hot resource market.

Fine talent with big name partners going after smart opportunities, often in brownfields areas, that could be enormous once they de-risk. They had strong, developing assets that could be taken into production as easily as they could be sold to a major. It was where an investor went when they believed in metals growth but didn’t want to settle for straight commodities futures. It was my kind of company.

Things went bad for Vena slowly at first, then all at once.

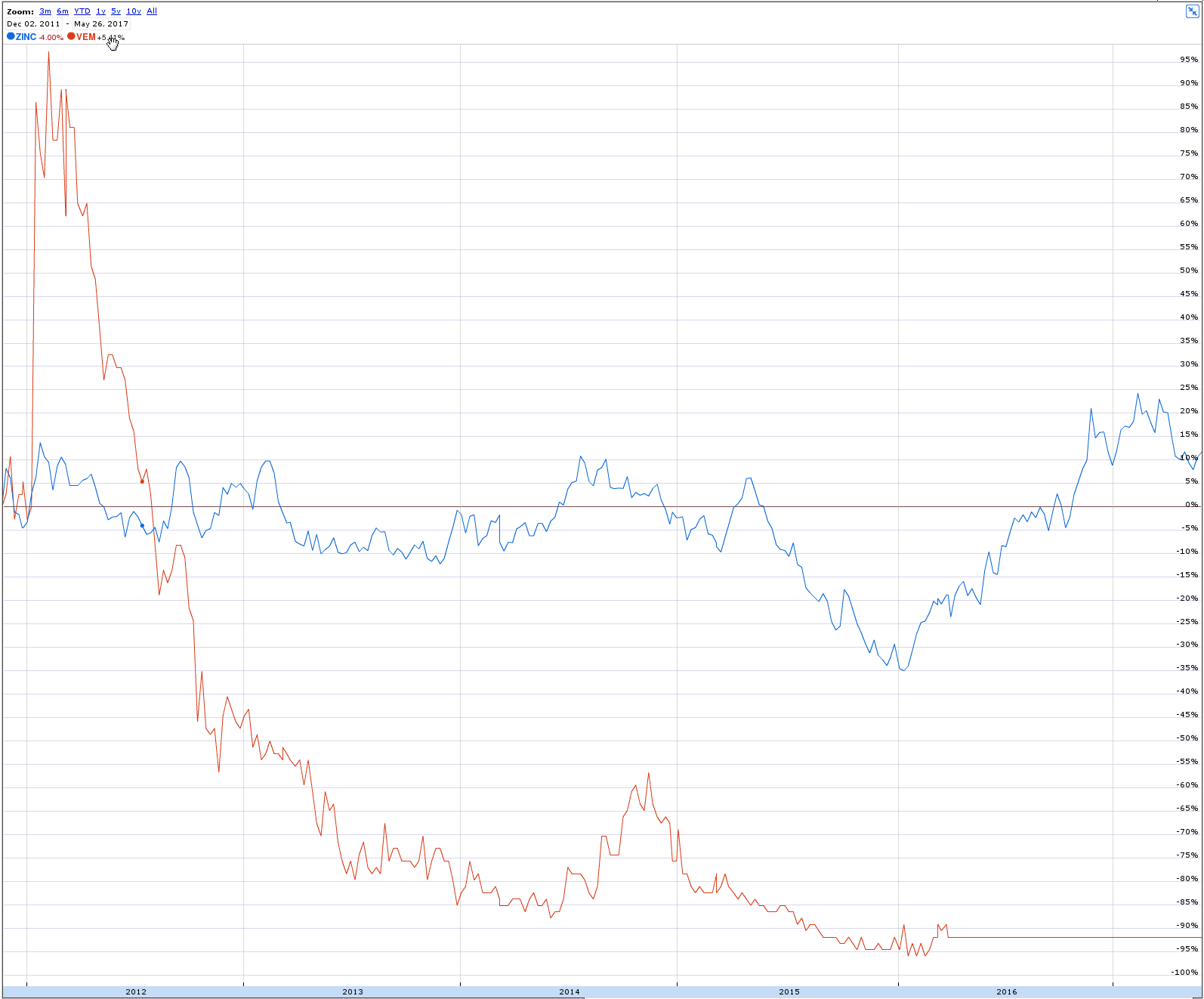

At the beginning of 2017, they were on the tail end of an extended beating that started with the financial collapse of 2008, continued with the depression of the commodities markets, and never really gave up.

When the commodities markets went bad and stayed bad back in 2011, the knives came out. A Glencore subsidiary that was once a credibility staple of Vena’s pitch (“…along with our partner Glencore…”), turned around and used a broad interpretation to their operating agreement to sue them for non-performance. Vena / Forrester ended up losing in a long and drawn out way as the market fell apart, and by 2017 the market was a long way past caring. A de-listing to the NEX effectively ended their relevance and they scraped along the bottom, trading between $0.05 and $0.10 with little volume. Tenacious as ever, the people at the re-christened Forrester Resources continued to acquire high-potential South American mineral properties, even as they were laid out on the mat, but nothing they did could make the market care.

And no kidding! Forrester had an $8M market cap, $400,000 in the bank, and Glencore standing there with their hand out for a $3 million judgment, still collecting interest. Under those circumstances, they wouldn’t be able to raise a dime with an option on the lost city of El Dorado.

Then, in February, along comes newly formed Zinc One with an all-stock offer for Forrester at 3x their market cap. After a few fits and starts, the Vancouver team backed by Kieth Neumeyer of Silver One (SVE.V) and First Mining Finance (FF.V) managed to get the deal done and raise an extra ten million dollars while they were at it.

So what gives? Why go after a direction-less mess that figured to fall apart eventually? Why not just pick up the pieces once it’s totally strung out?

Possibly because timing is everything.

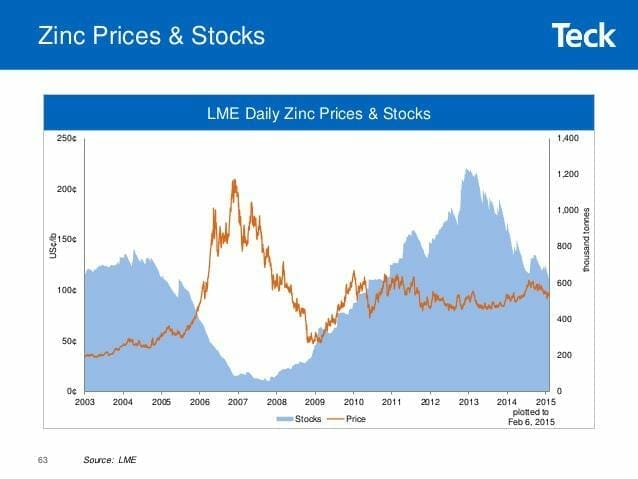

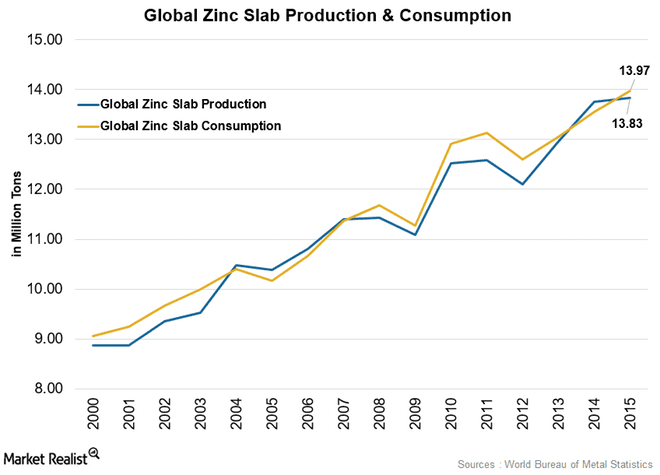

There’s nothing quite as cyclical as a resource market. Metals markets invented boom and bust and it’s always the same story: scarcity creates price inflation, price inflation creates exploration incentive, production comes too late to create supply, and the price runs. Eventually, supply catches up, usually right when demand dips, and the price craters again so that the cycle can continue. “…and on it goes this thing of ours.”

Vena / Forrester’s go at the last cycle looks, on reflection, like a kind of mania. Money was easy to come by, the market trusted them to find high-potential assets, they had big name partners… they almost never saw an opportunity they didn’t like.

Towards the end of their run, with less cash around, they got a bit more selective. In October of 2016, the small company acquired a zinc-oxide project called Bongara in north central Peru. In contrast to the busy polymetallic properties that got them in trouble with Glencore, Bongara is a fairly simple situation. It’s a series of known oxide zones near surface. They’ve been produced from recently, and exhibit high grades. Bongara has the makings of a straightforward resource proving job, and near term production is easy to envision. It’s the sort of thing that could become valuable in a hurry in a hot zinc market, to a company that didn’t have Glencore looking over their shoulder, ready to muscle them out of any serious money that they might notionally raise.

And a hot zinc market is what we’ve got.

Predictions of manufacturing economies slowing down have all proved to be premature. China’s manufacturing gauge just exceeded estimates for the second quarter running. That trend makes a draw on industrial metals like zinc both from manufacturing activities and to supply the associated infrastructure that is being built in those ever-emerging economies. Warehouse supplies are at all time lows, and it’s unclear so far where the production is going to come from to replace it.

It appears to be that time in the cycle, and the people behind Zinc One know a thing or two about timing.

Forrester could take forever to succeed or fail at getting themselves sorted out, and who knows where the assets are going to land once that process is done. This zinc market is happening now, and an easy to de-risk project like Bongara will only ever amount to something if the right people got a hold of it. So Zinc One hired the right people and made Forrester the proverbial offer they couldn’t refuse. Waiting for the stars to align would have been an amateur move.

Muscling it all into place is the order of the day, and that’s what we’re looking at here.

Jim Walchuck looks like the picture in the encyclopedia next to “mining engineer.” Bespectacled and wearing a permanent suspicious expression, he met me in a Vancouver cafe and patiently put up with idle chitchat so that we could get to the part where he could tell me about the project.

It’s a high grade oxide project, in a brownfields area. The geologists who are inclined to dream on these things are sure that the oxides are a sign of rich sulphide deposits somewhere at depth, and are keen to kick off extended exploration programs to solve the motherlode puzzle, but Walchuck doesn’t have those kinds of stars in his eyes. He’s an engineer, and he’s more concerned with the known oxide deposits and how to turn them into shippable concentrate.

Walchuck’s knack for envisioning holistic production scenarios, along with a great deal of experience and an excellent reputation, is the reason he’s here. He was brought in by deal makers who know what they want, and intend to set up something timely. At Bongara, Walchuck envisions ore being processed via a Waelz Kiln. Essentially, it’s a large cylinder in which zinc oxides are roasted with coal, evaporated into a condenser, and concentrated into a product that can be sold to a refinery.

Bongara’s near-term exploration profile appeals to both grade junkies and penny pinchers.

There’s no resource yet, but enough is known about the deposit to make Zinc One confident that a well planned exploration program will produce one. Grades are often north of 20% Zn, and the deposits have a fairly flat, near surface orientation. Walchuck tells me that this type of oxide formation is amenable to the use of a sprayable solution that turns zinc-rich mineralization bright red. That type of innovation ends up speeding up exploration time by showing field crews when they’re in the mineralization and when they’re not.

With that type of confidence and much of the exploration work already done, Walchuck projects that the company will be able to drill out the deposit with a resource by the end of the year, and conduct the necessary environmental studies as they go. Such a timeline puts them in position to do a PEA in the first half of 2018.

After the dust clears from the Forrester acquisition, Zinc One will have just shy of 100 million shares outstanding. That gives them a market cap around $60 million at this stage. They’ve raised enough cash to take them through that PEA. By virtue of having cash, properties and an active listing, they’re in a better position to negotiate with Glencore than Forrester was.

This is a company put together by professionals. They’ve created a deal designed to take immediate advantage of a Zinc market that doesn’t appear to be slowing down. Consumption exceeded supply in 2016, and between several high-proflie mine shutterings and the coming reserve decline at Teck’s Red Dog mine in Alaska, the writing appears to be on the wall for higher zinc prices in the near term.

The properties that spread Vena/Forrester’s attention around and contributed to their manic lack of focus are still around, and may make valuable spinouts or sales, but one doesn’t get the feeling that Zinc One is going to go chasing rainbows. They’ve built this company to go after a coming Zinc melt-up, outlined a clear execution timeline, and are in the process of going about it.

Zinc production-consumption graph courtesy Market Realist.

— Braden Maccke

FULL DISCLOSURE: Zinc One is an Equity.guru marketing client and we have purchased stock in the company.