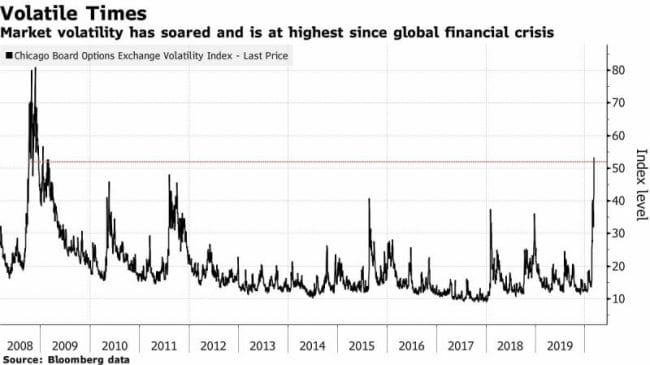

In the worst week for the US stock market since the financial crisis, the S&P500 fell more than 7.5%, and a full-blown price war rattled the markets over the weekend. Crude fell by over 20% and treasuries plummeted.

The lynchpin of the global financial markets – oil – dropped over 20% today, the story went from bad to worse in a matter of minutes. As capital moved away from equities, the 10-year US Treasury fell below 0.5% during the day but climbed to close at 0.57%. The 30-year yield closed at 1.00%. The market volatility index – VIX – is approaching levels not seen since the 2008 financial crisis.

And of course, it is a fact universally acknowledged that a stock market in need of an overdue correction is in want of fiscal policy intervention. President Trump said that he will discuss a payroll tax cut with Congress, which could provide “very substantial relief” to the US economy.

As soon as he said this, futures gained 1.5% at the Asian open in Tokyo.

Oil: From Bad to Worse

Despite the major selloff and volatile market today – the core story is about oil, which posted its biggest drop since the 1991 Gulf War. No sooner had the coronavirus caused a demand shock decreasing global demand for oil than Russia and Saudi Arabia decided to pump more of it.

Context: Oil is a major global commodity that is a primary resource used in pretty much everything and anything. The reason oil producers and cartels such as OPEC engage in conversation about production cuts is to artificially restrict supply, keeping prices steady.

How much?: Brent crude, the global gauge of oil prices, shed 24% to $34.36 a barrel, while U.S. crude futures dropped 25% to $31.13 a barrel. For both, it was the worst one-day selloff since 1991.

The Why: The OPEC (led by Saudi Arabia) proposed a production cut to Russia: extending production cuts of 2.1 million barrels through to the end of 2020, and make further cuts of 1.5 million barrels per day.

Russia disagreed, so Saudi Arabia threatened to reduce the price of oil and overproduce.

Do Canada/USA/Russia Belong the OPEC?: No. Canada, China, Russia, and The United States are non-members. The full list of members can be found here.

What’s Russia got to do with Oil?: Around 60% of the country’s exports and around 30% of the country’s GDP is dependant on oil. Russia is a net exporter of oil, so a fall in global oil prices affects its GDP and economy greatly.

Why would Russia disagree? Don’t production cuts and better oil prices help them?: Well, they disagreed because there are other players and other factors involved in the game. Oil is unique as a commodity in that it’s homogenous in its selling price (which is global) but inhomogeneous in its production cost (which are local).

The US recently became a net exporter of oil for the first time in decades, and because shale is in plenty in North America, it began to take up market share. Because it’s closer to Europe, low shipping costs mean greater market share for the US, which means a lesser market share for Russia.

Perhaps Russia enjoys greater margins and could stomach the loss from selling oil at low prices. Perhaps there are unit economic costs here, and it would’ve cost Russia more to collude with a production cut, and store oil instead of selling it. Or Perhaps Russia wanted to erode the US’ market share or simply hurt the US economy. Depending on the worldview you subscribe to, you can find alternative views.

What about the dollar? Well the US dollar is THE currency that oil is traded in, and such a sharp drop in oil prices makes other currencies depreciate against the US dollar. It’s no surprise then that the Canadian and Australian dollar depreciated against the USD.

With a stronger dollar, net importers of goods (in US Dollars) benefit, while net exporters of goods (in US Dollars) suffer. A stronger USD would theoretically result in a drop in US exports, and a rise in US imports.

This would make it more expensive for emerging market economies to buy oil as their currency depreciates against the dollar. It also becomes worse for every company that has any dollar-denominated debt outstanding, because currency fluctuations just made it worse for you to pay back your debt.

When I wrote the newsletter last Friday, I spoke of the CDX index that rose sharply, indicating that the cost of insuring corporate defaults skyrocketed in the wake of the coronavirus sellout. A stronger dollar is a contributing factor to this rise, for it becomes more expensive for companies to pay down their debt.

Has this happened before?: In 2014, a similar crash in oil prices happened when the US began expanding production and gaining market share. Here’s a detailed report on why oil crashed in 2014. As a direct result of this, the Russian Ruble declined by 59% relative to the US dollar.

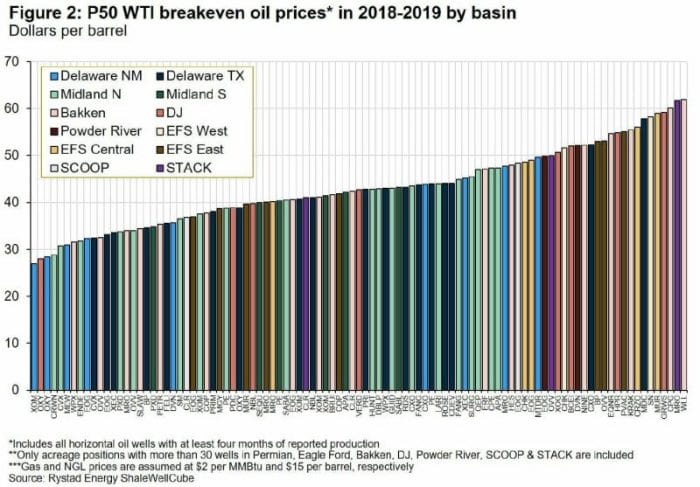

How Bad Is This?: Well, it could get pretty bad given that the vast majority of energy companies in the US need oil prices to be above $40/barrell (WTI) to breakeven. The number varies, but if prices continue to plummet, it could easily hurt North American energy producers, which are already companies with tons of dollar-denominated debt.

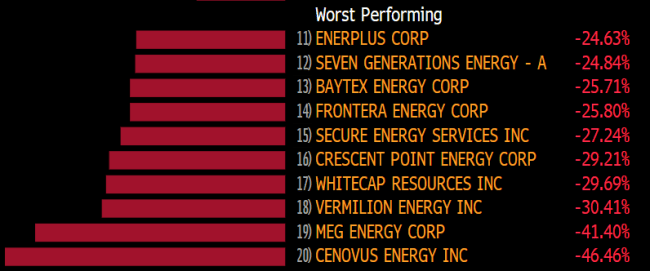

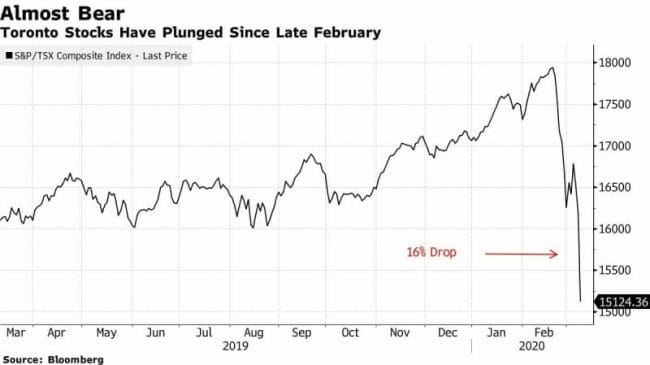

Will this affect Canadian Markets?: You tell me.

What’s Coronavirus got to do with it?: As a direct impact of the coronavirus, global oil demand has fallen. So we could potentially be facing a world with an excess supply of oil at cheaper prices, and a diminished demand as well. This could create an unhealthy cycle of bankruptcies and companies defaulting on their debt.

Layoffs would mean less consumer expenditure and a decrease in real wages. That would mean less demand for consumer goods, which in turn would affect profitability as companies would pile up inventory.

Booking Holdings and Host Hotels are two new firms that have joined the list of US companies to withdraw guidance. As WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said, “The threat of a pandemic has become very real.” Airlines and Travel companies are some of the first to bear the direct brunt of the economic impact of COVID-19.

On the Coronavirus, the number of cases in the US has topped 600 with 24 deaths, while the global tally sits at 113,000 confirmed cases and over 3,900 deaths.

How will this affect me?: Under ideal circumstances, a drop in oil prices would’ve meant greater margins for airline companies and other industries that rely on heavy usage of oil. However, because of the coronavirus, global travel has already declined sharply, and so airline companies might not be the greatest benefactor after all.

In some time, perhaps consumers will enjoy some savings from lower oil prices as they fill up their tanks of gas, but across the macroeconomic landscape, this could trigger bankruptcies, job losses, and a halt in capital spending.

Can this trigger a recession?: Perhaps. Look, I’m not a fortune teller and don’t know if overnight Russia and Saudi Arabia reach some type of accord and oil prices recover Tuesday at the open. I also don’t know if the Fed will cut rates further to weaken the dollar and preserve its status as the reserve currency for global trade.

What I do know is that in a market that was already having difficulty pricing in the demand and supply shocks that would stem from the impact of the coronavirus. The full-throttle price war on oil led by Saudi Arabia not only adds another dimension to the problem, but also makes existing ones cut deeper.

At this point, it’s a near certainty that the Federal Reserve will engage in some rate-cutting to devalue the dollar. But whether or not there is an accord on the oil front, is something time will tell.