There are several different kinds of resource investor out there and none of them are right.

There’s the drill results guy, who goes in before the drills do and plays for a good results call in a month or two. There’s the run-to-production guy, who only goes in once those drill results have been proven. And there’s the blue ribbon guy, who waits until all the pieces are in place, all the risk has been removed, and goes in when there’s ore being crushed and trucked out.

I’m a Moneyball guy. I like to go in when everyone else has passed by, missing something that I think is important, or when nobody has yet actually heard the story.

And the Quantum Minerals (QMC.V) story is simple.

- Lithium is a thing that is interesting.

- Quantum has a property that was supposed to, back in the day, become a big ass lithium mine, until the backside fell out of lithium prices

- The lithium is in spodumene, which is easily recoverable, and quickly into production

I could probably wrap it up right here, other than to add the company has a $4 million market cap, just did an oversubscribed financing to get things moving on the ground, and has two other properties that may bear fruit at some point.

In? Me too.

But let’s go deeper, because it gets better.

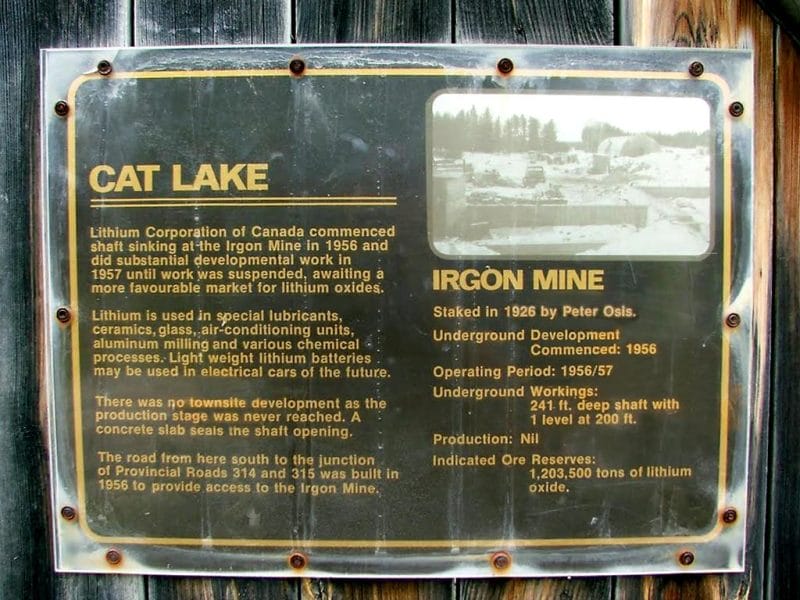

Back in the 1930’s, folks discovered that there was lithium in the ground just north of Cat Lake, Manitoba. So they started dropping drills into the ground to see how much. By the 1950’s, the Lithium Corporation of Canada had taken over the area and was set to build a mighty town above, as they plunged mine shafts down and brought roads in, and got ready for riches.

But the price of lithium tanked and the LCoC backed out, leaving the area to the trees, with only this highway marker to show they’d ever been there.

If you look at the top right corner there, that’s an image of the work being done, way back when.

So the years passed by and most tourists didn’t, but for one man who thankfully follows the old historian’s creed; “Always look at the plaque.”

While meandering down a dusty road, he happened to spot a highway marker, wiped away a few years of grime, read the words “lithium mine,” and made some calls.

Quantum Minerals duly inquired about mining rights, and was told there would be a $45,000 price tag, which reflected the fact that nobody has bumped into this thing in seventy years, more than it reflected its potential.

The Irgon Mine, which is the name of this old mine shaft complex, produces spodumene.

Let’s talk about spodumene. In fact, let’s let Geology.com talk about spodumene:

Spodumene often occurs in extremely large crystals. One of the earliest accounts of large spodumene crystals is from the Etta Mines, Black Hills, Pennington County, South Dakota. The United States Geological Survey, Bulletin 610 reports: “The crystals are often of enormous size. In the Etta Mine, where they are best exposed both in the open cut and tunnel, they frequently attain a diameter of 3 to 4 feet and a length of 30 feet. The largest “log” so far found was 42 feet long and 5 feet 4 inches in maximum diameter. This one log alone would yield 90 tons of spodumene.”

That’s a lot of spodumene. But where does the lithium come in?

Spodumene once served as the most important ore of lithium metal. Although it remains an important source of lithium, today most of the world’s lithium is produced from subsurface brines in Chile, Argentina, and China. These sources of lithium have lower production costs and are suitable for most uses. However, when lithium of highest purity is needed, spodumene is the source that is used.

This is important stuff. There’s loads of lithium out there. The planet Earth is lousy with lithium, frankly. It’s in Alberta oil wells, where it gets in the way of getting at the gas. It’s in salt brines. It’s in rock.

Getting lithium isn’t hard. Getting at it is, and getting it processed is tougher still.

If you’re pulling lithium out of the ground in South America presently, well done, you’re a top little earner. But if you’re planning to pull it out of the ground, out of salt brines and the like, you’re going to have a slow road to production because the leaching needed to get at the lithium is no easy feat.

In fact, technological issues and water rights problems are what has stymied the once hot Clayton Valley in Nevada, where lithium types staked like mad and ran up the stock price of everything just eighteen months ago.

When Nevada got too difficult (and dry), big players like Lithium X (LIX.V) took off for South America, where they’re fairly progressing things, but their work there has a fairly long timeline.

Contrast that to the work being done in the north, where the process for drawing lithium out of spodumene is as follows:

Admittedly, I couldn’t build that set up using my Home Depot gift card and some high school level chemistry knowledge, but others can – and will.

The simple fact of the matter is that Tesla wants North American lithium supply – it’s said so, and in fact I’m told that company has been actively talking to a handful of smaller energy metal plays (one being Iconic Minerals (ICM.V) recently about investing in extraction tech that would help get to and process US and Canada-based ore.

So South America will be great for folks needing lithium for smoke alarms and laptop batteries, but our old friends building the gigafactory want product from closer afield – and they don’t want to wait three years for it to properly leach.

Compare the video above, where you’re simply crushing rocks and working it through a small closed loop system over a series of days, to the video below, which shows the massive scale required in a salt brine operation, where leach ponds take months and years to evaporate using the sun. And also note the political problems involved, with all that water being needed, and the expansive impact on the environment.

So here we have, in spodumene, a higher grade product (which end users want), a cheaper and faster set up (which investors want), admittedly a higher cost product (which Tesla is okay with, as long as it’s local), which comes in chunks several feet across (which makes it easy to spot), and has a lower environmental impact and footprint than brines (which we all should want).

And here’s little Quantum Minerals with a property that, according to the historic estimates (admittedly, not NI 43-101 compliant, which is important to note) has “an estimated resource of more than 1.2M tonnes of spodumene-bearing pegmatite grading 1.5% Li2O.”

Historic metallurgical tests reported an 87% recovery from which a concentrate averaging 5.9% Li2o was obtained. A complete mining plant was installed on site designed to process 500 tons of ore per day and in addition, a three compartment shaft sunk to a depth of 74 meters. On the 61 metre level, lateral development was extended off the shaft for a total of 366 meters of drifting; from which six crosscuts transected the dike. The work was suspended in 1957, awaiting a more favourable market for lithium oxides and at this point the mine buildings were removed.

To get to it, assuming that historical data bears any semblance to reality, you’d need mine shafts – thankfully, the helpful now-great grandparents of Manitoba plonked some down for them seventy years ago.

And once you’ve used those shafts to get at the rock, you’ll need roads to transport the product. Thankfully, Manitoba’s founding fathers have put Provincial Highway 314 right past the thing, which leads to Winnipeg, just 150 miles away.

That’s close enough that you don’t even need to build a town to support your workers. They can lie and play in the ‘Peg, and commute to work down the highway.

20 kms to the north of the Irgon Mine is the Tanco Mine. Says the company:

“The Tanco Mine went into production in 1969 and produced tantalum, cesium and lithium concentrate. It was previously North America’s largest and sole producer of spodumene (Li), tantalite (Ta) and pollucite (Cs).

That’s spodumene. Pretty.

The only part of this entire process that spodumene doesn’t win on, against brines, is that the brines are cheaper to operate on a mass scale. Let’s tackle this once and for all.

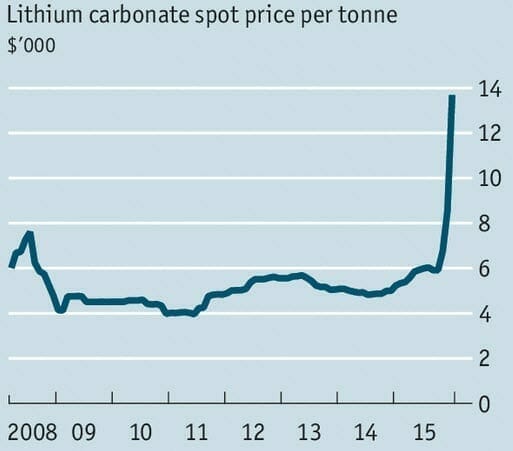

First, lithium prices have skyrocketed over the last few years. Have you noticed electronics getting more expensive as a result?

Neither have I, even with lithium prices having gone crazy nuts.

The simple fact of the matter is, there’s not that much lithium to be had in a lithium-ion battery. It’s lousy with copper and nickel and cobalt and manganese and graphite. But lithium? There’s about a teaspoon of it in your cellphone, so if you tripled the cost of that teaspoon, you wouldn’t notice a price rise at the end user level.

Even if we look at the bigger users of lithium, the numbers don’t prohibit higher cost production. There’s maybe 63 kilos of lithium in a 453 kilogram Tesla Model S battery pack. That’s a decent amount, but let’s do some math.

If there’s 63 kg of lithium in a single Tesla battery, that comes out to 15 batteries per tonne of lithium. If the lithium is selling at $25,000 per tonne, that comes out to $1600 of lithium in each battery.

Let’s be cynical and say spodumene lithium isn’t getting a better price for being higher grade (it is) and is competing directly against the South American leach product on an even level. If you charged a premium of 30% more because it’s SO expensive to crush rock instead of sit for three years waiting for the sun to evaporate stuff (estimates suggest a $2 per lb crushing cost as opposed to a $1 evaporation cost, or $4000 extra per tonne for crushed, roughly half what we’re calculating here), that’s an extra $500 to the cost of your Tesla.

Not exactly death by strangulation. And for that, you get local product of a high grade in quick turnaround time.

Spodumene makes sense. And if we agree on that, then we have to look to see who’s going the spodumene route.

Here’s the thing: Not too many are. Spodumene mining was big in North Carolina for a long time, and kept the lights on in the US lithium market until the call for it dropped off low enough to make South American plays better.

But that was before the lithium ion battery explosion, and Tesla, and gigafactories, and every single car company needing an electric model to compete, and Tesla building a higher market cap than Ford, and Ford’s CEO being sacked for failing to come up with a Tesla killer.

We are in a period of time where not only is lithium demand going to keep climbing, but that demand will outstrip the ability of producers currently in the space to produce quickly enough to meet that need.

Quantum Minerals is a $4 million bet in a space that nobody can truly guess the future size of, except to say that it will dwarf what we have now.

Is it likely that the Canadian government, and the Manitoba government, will want to move heaven and earth to not only become a global lithium supplier, but to kickstart mining in an area that has nothing else to produce? I’d say so.

Is it likely that technology will evolve that will make crushing rock found in large quantities in Manitoba more affordable? Yerp.

Now, let’s not get carried away and suggest Quantum is going to be pumping out lithium gravel inside the month. There’s some way to go. In fact, the company has outlined what the next steps are:

QMC’s immediate objectives will be to arrange financing, compile all historical data then subsequently initiate a plan for exploration of the property with the goal to ultimately determine the economics of possible near term lithium production from the Irgon pegmatite dike.

So we can expect, now that they’ve got their money raised, that we’ll be seeing exploration news imminently, which will rock that stock if it finds what the old timers found.

By all means, don’t buy any. Keep a cold cynical eye on them and expect nothing, demanding the highest levels of success before you go in. I get that.

But watchlist them. Lithium is a thing, and Quantum is the cheapest bet on the markets if you want to get in early.

— Chris Parry

FULL DISCLOSURE: Quantum Minerals is an Equity.Guru marketing client, and we bought stock in the recent financing.

What happened to QMCQF It has not traded since June 19th. I bought 10000 shares and it has not moved for some reason. I cannot find a trading halt online so just wondering if you can provide any information?

Sorry that is June 9th not the 19th.