On May 28, 2017 a Chinese state-controlled but publicly-traded gold company, Shandong Gold Group (600547.SS) announced that it had discovered “China’s Biggest Gold Mine” with 382 tons of gold reserves.

The next morning, the phrase “Gold Mine” was repeated in headlines by Bloomberg News, Yahoo Finance, Kitco, Sputnik International, China Daily, etc. I’ve met commodity brokers who can’t read a drill log, but most retail investors know the difference between a “mine” and a “deposit.”

The distinction is important. Turning a deposit into a mine involves drilling, permitting, engineering reports, feasibility studies – and most importantly – proving that the metal can be extracted profitably.

Exploration companies are like armies of baby turtles scuttling across the beach toward the ocean. 99% of them end up masticated by seagulls.

Commodity companies traded on Canadian stock exchanges must adhere to the National Instrument 43-101 for the Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects, which requires them to communicate to investors in standardised geological language.

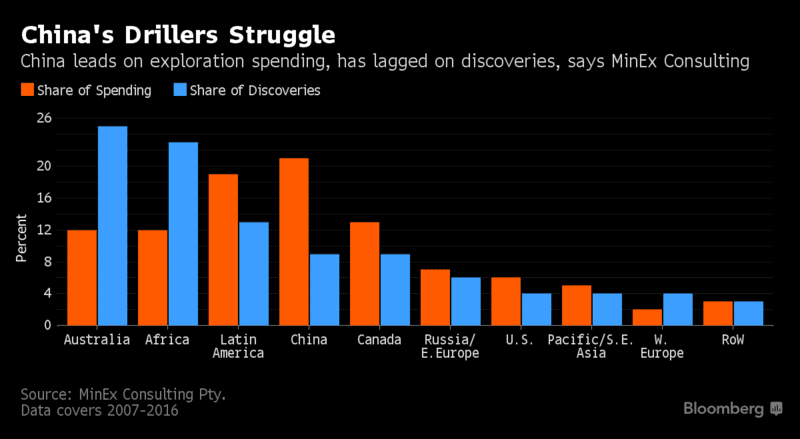

China does not follow 43-101 protocols, nor does it have an equivalent set of standards. China’s current mineral reporting system is designed for government oversight, not capital markets.

This lack of scientific rigor has muted foreign investment in Chinese metal projects and made their own drill programs less successful.

Shandong Gold is traded on the Shanghai stock exchange. It has a market cap of about $1 billion, a forward P/E of 33 and a 2016 net profit of $187 million.

Following the news of the “Gold Mine Discovery” shares rose a modest 2.8% in Shanghai – an indication that Chinese investors took the news of the monster “gold mine” with a grain of salt.

But can a hyperbolic press release from a Chinese gold company affect North American investors?

Yes.

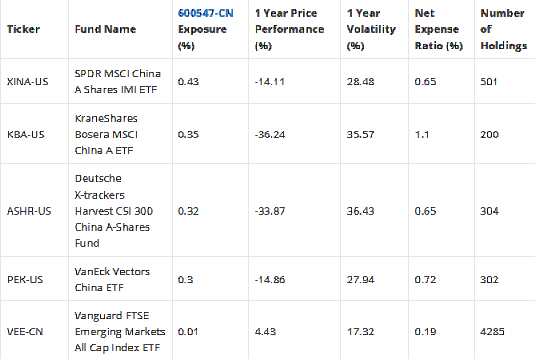

According to Capital Cube, the following internationally traded ETFs own part of Shandong Gold:

The normalisation of disinformation also affects companies like like Silvercorp Metals (SVM.T), China Gold (CGC.T) and Minco Silver (MSV.T) that have active projects in China.

With a population of 1.4 billion and a young, swelling consumer class, it’s no wonder Canadian juniors scramble to include China as part of their growth story.

Developing a new insulin pump? There’s a 110 million people in China with diabetes. Designing yoga pants? China’s active clothing market is expanding 20% a year. Cell phones? Yes – they’re popular devices in the Middle Kingdom.

But the bigger lesson to be extracted from the hyperbolic Shandong Gold press release, is the importance of critically analysing all news coming out of China.

The $6 billion TSX forestry company Sino-Forest collapsed in 2011 after it was discovered they didn’t own any trees. If it sounds like I’m China-bashing, you’ve got me wrong.

I live part-time in China, speak Mandarin (badly), and have developed a deep affection for the country and its people. Human rights issues? Of course. But the Central Government lifted 500 million people out of extreme poverty in a single generation. That’s not nothing.

The fact is, you will never meet a native Chinese citizen – from any walk of life – who thinks democracy is a workable plan in China in 2017.

Diligent investors do rigorous research. If you are a shareholder in a company with a footprint in China, that research may not provide clarity.

That’s not because the Chinese are any more dishonest than we are. It’s just that the culture is so radically different it creates a fun-house mirror of illusions.

The first time I went to China in 2011, I spun my wheels in Beijing for 17 days waiting for a deal to close – while the contract ping-ponged back and forth between lawyers in Shanghai and Vancouver.

Since the Chinese were spending tens of thousands in legal fees, I assumed the deal was progressing. Eventually I realised the Chinese had no intention of signing the contract. It was their complicated, expensive way of saying “no”.

Well, I thought, lesson learned.

Possibly. But the “learning” never ends.

In fact I’m convinced I haven’t reached base-camp on the mountain of incomprehension.

Here’s an example of China’s on-going ability to baffle me: a month ago I was in a Beijing bar called “Slow Boat”, eating burgers and drinking Russian Stout.

A 28-year-old woman at my table told a story about her childhood friend. The story involved four people. As I listened to the story, the psychological dynamics seemed reasonably straight forward.

Her friend, Zhong, was an only child from a wealthy family. Educated in Perth, he spoke perfect English and drove a Porsche. His bright pretty girlfriend came from a village in the south. She spoke with a rural accent, had a high-school education and worked as a waitress.

Zhong’s parents disapproved of the union. They refused to talk to his girlfriend and banished her from all family functions. This romantic relationship was a great source of tension between Zhong and his parents.

In May of 2016, Zhong crashed his Porsche into a telephone pole and died. The girlfriend was not invited to the funeral. However the parents did an about-face when they discovered she was pregnant. Since Zhong had no siblings, this fetus was their only chance to continue the family name.

Zhong’s parents ordered a DNA test on the fetus. When it was confirmed the unborn child was indeed their biological kin, they invited the young woman to a fancy restaurant, to formally welcome her into the bosom of the family.

After a cordial hot pot, the young pregnant woman handed the parents a slip of paper with her banking information. She instructed them to deposit 1 million RMB ($150,000 USD) in her account by next Friday, or she would abort the baby.

Three days later, the parents contacted her with a counter-offer of 600,000 RMB. The next day she aborted the baby and never spoke to them again.

The story’s 3rd Act baffled me. Why didn’t the impoverished pregnant woman continue with the negotiation? Was the parents’ initial rejection of her justified? If she’d truly loved their son – surely she wouldn’t have used his unborn child to extort a ransom?

My female friend scoffed at my soggy-brained western interpretation. The waitress did love Zhong. That’s why the family’s rejection of her was so wounding. The lowball offer for a grandchild was another dagger of disrespect. For that reason she decided to condemn them to eternal suffering.

Further, it was explained to me, the 1 million RBM was a not a “ransom”. Single mothers (divorced or widowed) in China are virtually unmarryable. So it is only fair that the wealthy family compensate her for the financial sacrifice of giving birth to their grandchild.

So despite all my experience living and doing business in China, I failed to grasp the motivations behind the main “actors” in this Shakespearian tragedy.

The moral of this story, for foreign investors, is to be keenly aware that all stories coming out of China may contain invisible subplots.

Shandong Gold announced that the deposit is 2 kilometres long and “part of it” [editor’s emphasis] has a thickness of 67 meters. The press release did not divulge what part of it, or how big the part was.

Why did Bloomberg News not call “bullshit” on Shandong Gold’s press release?

Probably because there is a general assumption that, “things are different in China.”

Well yes, things are. So different that a gold deposit can tuck itself into bed and wake up as a gold mine.

— Lukas Kane

FULL DISCLOSURE: Shangdong Gold is in no way, shape or form, an Equity.Guru marketing client, because we don’t deal in fantasy.

Mr. Parry, you are sexy when you are angry. Thoroughly enjoyed your hot beatdown of Media Central (FLYY.C). That said, the notion of owning hundreds of papers and syndicating SOME of the content is not entirely crazy. If Kitsilano Karen wants to read a review of the Mission Impossible V111 – does she really care if the reviewer lives in Yaletown or Toronto? Probz not. Paying one reviewer and publishing the review in 80 markets is a good business model. Corporate product syndicates well. Hand-made, local product – not so much. 25 years ago, I used to devour the The Georgia Straight every week cover-to-cover. They had a disciplined journalistic formula – hire experts: ballet, dance, wine, TV, Film, theatre, city hall, Tech…they had an expert for everything. And for the most part, the writers wrote well. Slowly, they fouled up their own formula. As an example, firing the best theater critic in Canada. Admittedly, that critic wasn’t well-liked, but if you put on a play in Vancouver, his opinion mattered. The Georgia Straight has been dying for at least 10 years. I suspect you are right: Media Central will kill it completely.

Agree to a point, but I think in a time where we can choose to read a review from anywhere online, we increasingly look for a unique and educated voice we trust, not just whatever knucklehead happens to have landed on the wire.

If I’m looking to figure out if it’s worth going to that new indie film at the Park Theatre, do I want to hear from a local critic who may share my sensibility on the world, or the guy who reviewed it from the Texarcana Bulletin and sometimes reviews the ammo selection at WalMart? What plays in New York doesn’t always play so hot in Tuscaloosa..