(PDF format, 1.95 MB, 112 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Published: 2016-12-13

The Honourable Jody Wilson-Raybould

Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada

The Honourable Jane Philpott

Minister of HealthThe Honourable Ralph Goodale

Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness

Dear Ministers,

Please find attached the final report of the Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation.

This report is the product of our consultations with Canadians, provincial, territorial and municipal governments, Indigenous governments and representative organizations, youth, patients and experts in relevant fields.

It has been a privilege to consult with so many people over the last five months, and we are deeply thankful to all those who provided their input, time and energy to us.

We hope that this report will be useful to you and your Cabinet colleagues as you move forward with the legalization and regulation of cannabis.

A. Anne McLellan (Chair)

Mark A. Ware (Vice Chair)

Susan Boyd (Member)

George Chow (Member)

Marlene Jesso (Member)

Perry Kendall (Member)

Raf Souccar (Member)

Barbara von Tigerstrom (Member)

Catherine Zahn (Member)

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Executive Summary

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Minimizing Harms of Use

- Chapter 3: Establishing a Safe and Responsible Supply Chain

- Chapter 4: Enforcing Public Safety and Protection

- Chapter 5: Medical Access

- Chapter 6: Implementation

- Annex 1: Biographies of Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation Members

- Annex 2: Terms of Reference

- Annex 3: Acknowledgements

- Annex 4: Discussion Paper ‘Toward the Legalization, Regulation and Restriction of Access to Marijuana’

- Annex 5: Executive Summary: Analysis of consultation input submitted to the Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation

Foreword

When the Task Force first assembled in June 2016, we each brought a range of individual perspectives on cannabis. Over the months that followed, we came to appreciate the collective importance of our varied viewpoints and to recognize the potential impact of our work. This report is the result of a truly national collaboration, and we are proud to have been involved in it.

We have discovered that the regulation of cannabis will touch every aspect of our society. One of the predominant features of our deliberations has been the diversity of opinions, emotions and expertise expressed by those who came forward. People and organizations gave generously of their time and reflections. We explored the issue in remote corners of Canada as well as outside our borders. We heard from parents, patients, practitioners, politicians, police and the media. Our focus ranged from global treaty obligations to the homes and municipalities in which we live. We heard anxiety about such things as driving, youth access and “sending the wrong message,” but we also heard a desire to move away from a culture of fear around cannabis and to acknowledge the existence of more positive medical and social attributes. Meanwhile, as we went about our mandate, dispensaries continued to challenge communities and law enforcement, new research findings emerged, new regulations appeared, and the media shone their light on issues of quality and regulatory gaps.

Because of this complexity and diversity of input, and the challenges associated with designing a new regulatory framework, we recognize that there will be much discussion around the implications of our recommendations. However, like scraping ice from the car windows on a cold winter morning, we believe that we can now see enough to move forward.

The current paradigm of cannabis prohibition has been with us for almost 100 years. We cannot, and should not, expect to turn this around overnight. While moving away from cannabis prohibition is long overdue, we may not anticipate every nuance of future policy; after all, our society is still working out issues related to the regulation of alcohol and tobacco. We are aware of the shortcomings in our current knowledge base around cannabis and the effects of cannabis on human health and development. As a result, the recommendations laid out in this report include appeals for ongoing research and surveillance, and a flexibility to adapt to and respond to ongoing and emerging policy needs.

This report is a synthesis of Canadian values, situated in the times in which we live, combined with our shared experiences and concerns around a plant and its products that have touched many lives in many ways. For millennia, people have found ways to interact with cannabis for a range of medical, industrial, spiritual and social reasons, and modern science is only just beginning to unpack the intricacies of cannabinoid pharmacology. We are now shaping a new phase in this relationship and, as we do so, we recognize our stewardship not just of this unique plant but also of our fragile environment, our social and corporate responsibilities, and our health and humanity. This report is a beginning; we all have a role to play in the implementation of this new, transformative public policy.

In closing, we recognize and thank all those who contributed to our work, in particular our colleagues on the Task Force, the Secretariat and Eric Costen, who provided outstanding leadership. We formally acknowledge Prime Minister Justin Trudeau for his vision in initiating this process and for seeing it through. Finally, we thank the Ministers of Health, Justice and Public Safety for trusting us to prepare and deliver this report. On behalf of all Canadians, we now place our trust in our Government to enable and enact the processes required to make the legalization and regulation of cannabis a reality.

Anne McLellan

Chair

Mark A. Ware

Vice Chair

Ottawa, November 2016

Executive Summary

Introduction: Mandate, Context and Consultation Process

On June 30, 2016, the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, and the Minister of Health announced the creation of a nine-member Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation (“the Task Force”). Our mandate was to consult and provide advice on the design of a new legislative and regulatory framework for legal access to cannabis, consistent with the Government’s commitment to “legalize, regulate, and restrict access.”

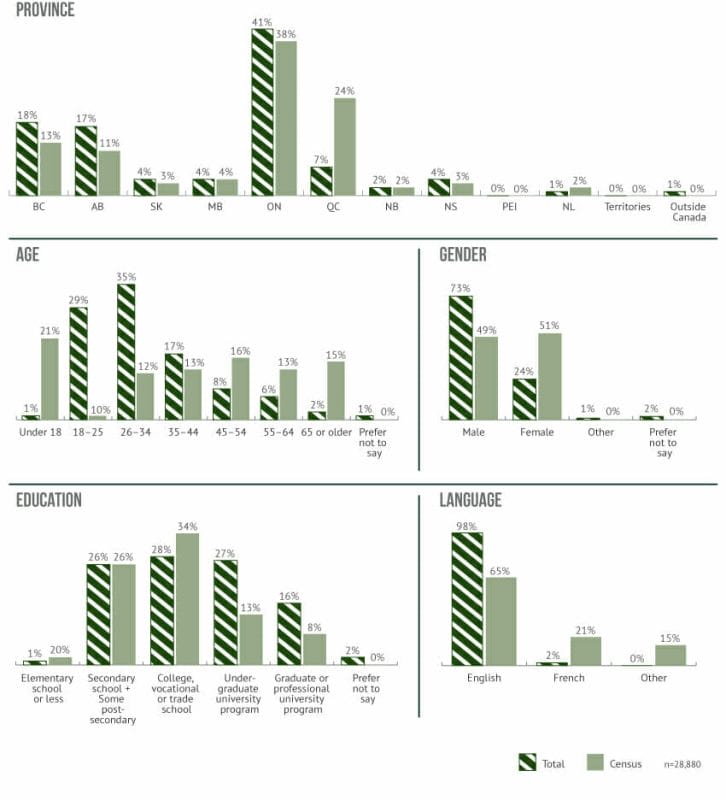

To fulfill our mandate, we engaged with provincial, territorial and municipal governments, experts, patients, advocates, Indigenous governments and representative organizations, employers and industry. We heard from many other Canadians as well, including many young people, who participated in an online public consultation that generated nearly 30,000 submissions from individuals and organizations. The Task Force looked internationally (e.g., Colorado, Washington State, Uruguay) to learn from jurisdictions that have legalized cannabis for non-medical purposes, and we drew lessons from the way governments in Canada have regulated tobacco and alcohol, and cannabis for medical purposes.

A Discussion Paper prepared by the Government, entitled “Toward the Legalization, Regulation and Restriction of Access to Marijuana,” informed the Task Force’s work and helped to focus the input of many of the people from whom we heard. The Discussion Paper identified nine public policy objectives. Chief among these are keeping cannabis out of the hands of children and youth and keeping profits out of the hands of organized crime. The Task Force set out guiding principles as the foundation of our advice to Ministers: protection of public health and safety, compassion, fairness, collaboration, a commitment to evidence-informed policy and flexibility.

In considering the experience of other jurisdictions and the views of experts, stakeholders and the public, we sought to strike a balance between implementing appropriate restrictions, in order to minimize the harms associated with cannabis use, and providing adult access to a regulated supply of cannabis while reducing the scope and scale of the illicit market and its social harms. Our recommendations reflect a public health approach to reduce harm and promote health. We also took a precautionary approach to minimize unintended consequences, given that the relevant evidence is often incomplete or inconclusive.

Minimizing Harms of Use

In taking a public health approach to the regulation of cannabis, the Task Force proposes measures that will maintain and improve the health of Canadians by minimizing the harms associated with cannabis use.

This approach considers the risks associated with cannabis use, including the risks of developmental harms to youth; the risks associated with patterns of consumption, including frequent use and co-use of cannabis with alcohol and tobacco; the risks to vulnerable populations; and the risks related to interactions with the illicit market. In addition to considering scientific evidence and input from stakeholders, the Task Force examined how other jurisdictions have attempted to minimize harms of use. We examined a range of protective measures, including a minimum age of use, promotion and advertising restrictions, and packaging and labelling requirements for cannabis products.

In order to minimize harms, the Task Force recommends that the federal government:

- Set a national minimum age of purchase of 18, acknowledging the right of provinces and territories to harmonize it with their minimum age of purchase of alcohol

- Apply comprehensive restrictions to the advertising and promotion of cannabis and related merchandise by any means, including sponsorship, endorsements and branding, similar to the restrictions on promotion of tobacco products

- Allow limited promotion in areas accessible by adults, similar to those restrictions under the Tobacco Act

- Require plain packaging for cannabis products that allows the following information on packages: company name, strain name, price, amounts of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) and warnings and other labelling requirements

- Impose strict sanctions on false or misleading promotion as well as promotion that encourages excessive consumption, where promotion is allowed

- Require that any therapeutic claims made in advertising conform to applicable legislation

- Resource and enable the detection and enforcement of advertising and marketing violations, including via traditional and social media

- Prohibit any product deemed to be “appealing to children,” including products that resemble or mimic familiar food items, are packaged to look like candy, or packaged in bright colours or with cartoon characters or other pictures or images that would appeal to children

- Require opaque, re-sealable packaging that is childproof or child-resistant to limit children’s access to any cannabis product

- Additionally, for edibles:

- Implement packaging with standardized, single servings, with a universal THC symbol

- Set a maximum amount of THC per serving and per product

- Prohibit mixed products, for example cannabis-infused alcoholic beverages or cannabis products with tobacco, nicotine or caffeine

- Require appropriate labelling on cannabis products, including:

- Text warning labels (e.g., “KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN”)

- Levels of THC and CBD

- For edibles, labelling requirements that apply to food and beverage products

- Create a flexible legislative framework that could adapt to new evidence on specific product types, on the use of additives or sweeteners, or on specifying limits of THC or other components

- Provide regulatory oversight for cannabis concentrates to minimize the risks associated with illicit production

- Develop strategies to encourage consumption of less potent cannabis, including a price and tax scheme based on potency to discourage purchase of high-potency products

- Require all cannabis products to include labels identifying levels of THC and CBD

- Enable a flexible legislative framework that could adapt to new evidence to set rules for limits on THC or other components

- Develop and implement factual public education strategies to inform Canadians as to risks of problematic use and lower-risk use guidance

- Conduct the necessary economic analysis to establish an approach to tax and price that balances health protection with the goal of reducing the illicit market

- Work with provincial and territorial governments to determine a tax regime that includes equitable distribution of revenues

- Create a flexible system that can adapt tax and price approaches to changes within the marketplace

- Commit to using revenue from cannabis as a source of funding for https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistration, education, research and enforcement

- Design a tax scheme based on THC potency to discourage purchase of high-potency products

- Implement as soon as possible an evidence-informed public education campaign, targeted at the general population but with an emphasis on youth, parents and vulnerable populations

- Co-ordinate messaging with provincial and territorial partners

- Adapt educational messages as evidence and understanding of health risks evolve, working with provincial and territorial partners

- Facilitate and monitor ongoing research on cannabis and impairment, considering implications for occupational health and safety policies

- Work with existing federal, provincial and territorial bodies to better understand potential occupational health and safety issues related to cannabis impairment

- Work with provinces, territories, employers and labour representatives to facilitate the development of workplace impairment policies

The Task Force further recommends that:

- In the period leading up to legalization, and thereafter on an ongoing basis, governments invest effort and resources in developing, implementing and evaluating broad, holistic prevention strategies to address the underlying risk factors and determinants of problematic cannabis use, such as mental illness and social marginalization

- Governments commit to using revenue from cannabis regulation as a source of funding for prevention, education and treatment

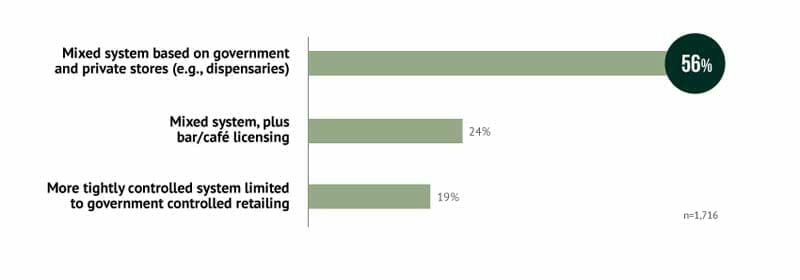

Establishing a Safe and Responsible Supply Chain

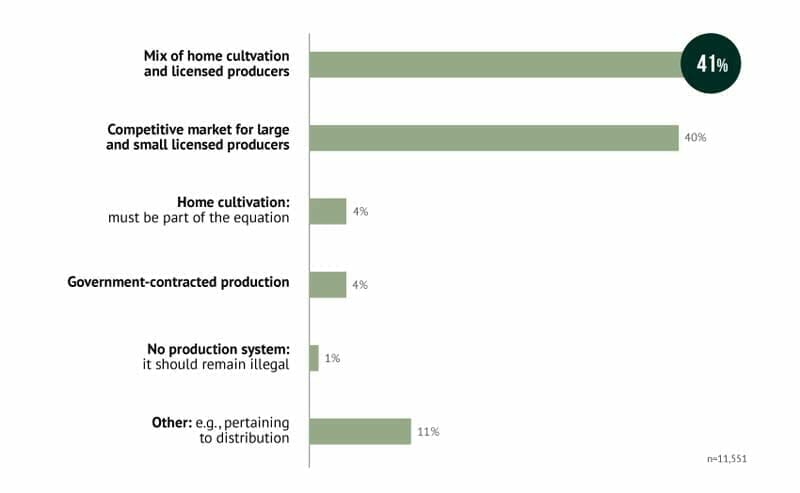

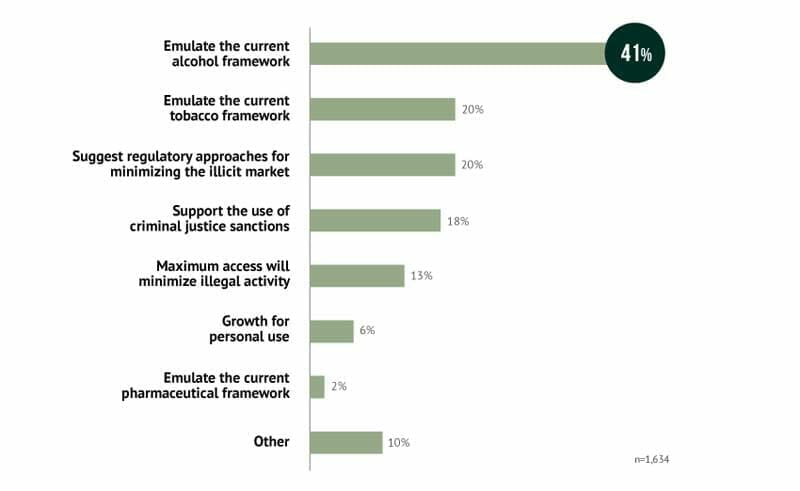

The cannabis supply chain includes production (including cultivation and manufacturing), distribution and retail. As part of our deliberations, we considered the most appropriate roles for the federal, provincial, territorial and local governments, given their areas of responsibility, capacity and experience. We were asked to give consideration to the participation of smaller producers, to the environmental impact of production, and to the regulation of industrial hemp under a new system. We heard about the pros and cons of different models for the retail market and about concerns regarding the sale of cannabis in the same location as alcohol or tobacco. We examined the question of personal cultivation in light of the experience of other jurisdictions, as well as the opinions of experts and the Canadian public.

To this end, the Task Force recommends that the federal government:

- Regulate the production of cannabis and its derivatives (e.g., edibles, concentrates) at the federal level, drawing on the good production practices of the current cannabis for medical purposes system

- Use licensing and production controls to encourage a diverse, competitive market that also includes small producers

- Implement a seed-to-sale tracking system to prevent diversion and enable product recalls

- Promote environmental stewardship by implementing measures such as permitting outdoor production, with appropriate security measures

- Implement a fee structure to recover https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistrative costs (e.g., licensing)

- Regulate CBD and other compounds derived from hemp or from other sources

The Task Force recommends that the wholesale distribution of cannabis be regulated by provinces and territories and that retail sales be regulated by the provinces and territories in close collaboration with municipalities. The Task Force further recommends that the retail environment include:

- No co-location of alcohol or tobacco and cannabis sales, wherever possible. When co-location cannot be avoided, appropriate safeguards must be put in place

- Limits on the density and location of storefronts, including appropriate distance from schools, community centres, public parks, etc.

- Dedicated storefronts with well-trained, knowledgeable staff

- Access via a direct-to-consumer mail-order system

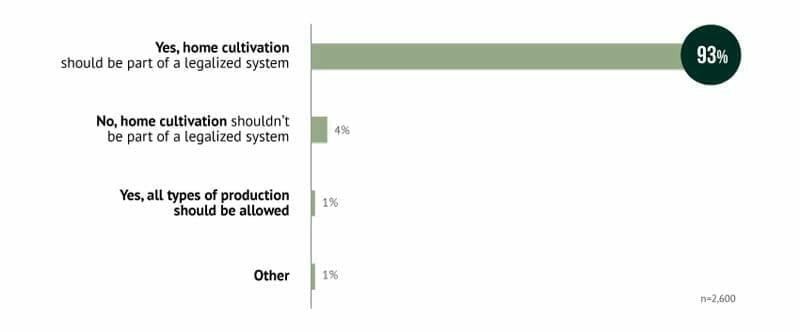

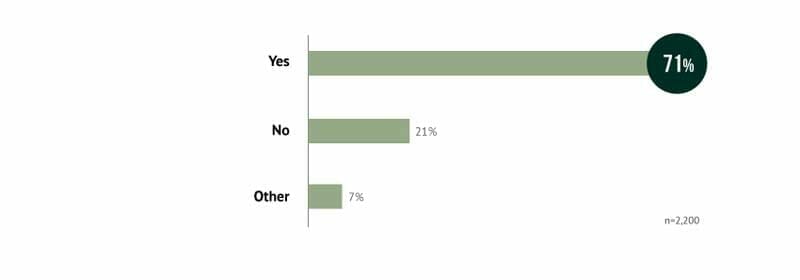

The Task Force recommends allowing personal cultivation of cannabis for non-medical purposes with the following conditions:

- A limit of four plants per residence

- A maximum height limit of 100 cm on the plants

- A prohibition on dangerous manufacturing processes

- Reasonable security measures to prevent theft and youth access

- Oversight and approval by local authorities

Enforcing Public Safety and Protection

We believe that the new legal regime must be clear to the public and to law enforcement agencies, with enforceable rules and corresponding penalties that are proportional to the contravention.

In formulating our recommendations, we considered various ways of dealing with those who break the law and contravene rules, ranging from https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistrative to criminal sanctions. We were urged to avoid criminalizing youth. We looked at questions of personal possession limits and the public consumption of cannabis, and considered whether existing laws or a new law would provide the most appropriate legal framework for the new system.

We carefully considered the scientific and legal complexities surrounding cannabis-impaired driving, recognizing the concerns of Canadians about this issue. We learned of the various approaches used to address cannabis-impaired driving both in Canada and abroad, including the possibility of establishing a per se limit for THC – that is, a level deemed to be consistent with significant psychomotor impairment and increased risk of crash involvement. Our recommendations reflect the fact that the current scientific understanding of cannabis impairment has gaps and that more research and evidence, investments in law enforcement capacity, technology and tools, and comprehensive public education are needed urgently.

To this end, the Task Force recommends that the federal government:

- Implement a set of clear, proportional and enforceable penalties that seek to limit criminal prosecution for less serious offences. Criminal offences should be maintained for:

- Illicit production, trafficking, possession for the purposes of trafficking, possession for the purposes of export, and import/export

- Trafficking to youth

- Create exclusions for “social sharing”

- Implement https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistrative penalties (with flexibility to enforce more serious penalties) for contraventions of licensing rules on production, distribution, and sale

- Consider creating distinct legislation – a “Cannabis Control Act” – to house all the provisions, regulations, sanctions and offences relating to cannabis

- Implement a limit of 30 grams for the personal possession of non-medical dried cannabis in public with a corresponding sales limit for dried cannabis

- Develop equivalent possession and sales limits for non-dried forms of cannabis

The Task Force recommends that jurisdictions:

- Extend the current restrictions on public smoking of tobacco products to the smoking of cannabis products and to cannabis vaping products

- Be able to permit dedicated places to consume cannabis such as cannabis lounges and tasting rooms, if they wish to do so, with no federal prohibition. Safeguards to prevent the co-consumption with alcohol, prevent underage use, and protect health and safety should be implemented

With respect to impaired driving, the Task Force recommends that the federal government:

- Invest immediately and work with the provinces and territories to develop a national, comprehensive public education strategy to send a clear message to Canadians that cannabis causes impairment and that the best way to avoid driving impaired is to not consume. The strategy should also inform Canadians of:

- the dangers of cannabis-impaired driving, with special emphasis on youth; and

- the applicable laws and the ability of law enforcement to detect cannabis use

- Invest in research to better link THC levels with impairment and crash risk to support the development of a per se limit

- Determine whether to establish a per se limit as part of a comprehensive approach to cannabis-impaired driving, acting on findings of the Drugs and Driving Committee, a committee of the Canadian Society of Forensic Science, a professional organization of scientists in the various forensic disciplines

- Re-examine per se limits should a reliable correlation between THC levels and impairment be established

- Support the development of an appropriate roadside drug screening device for detecting THC levels, and invest in these tools

- Invest in law enforcement capacity, including Drug Recognition Experts and Standardized Field Sobriety Test training and staffing

- Invest in baseline data collection and ongoing surveillance and evaluation in collaboration with provinces and territories

The Task Force further recommends that all governments across Canada consider the use of graduated sanctions ranging from https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistrative sanctions to criminal prosecution depending on the severity of the infraction. While it may take time for the necessary research and technology to develop, the Task Force encourages all governments to implement elements of a comprehensive approach as soon as feasible, including the possible use of https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistrative sanctions or graduated licensing with zero tolerance for new and young drivers.

Medical Access

Canada’s medical cannabis regime was created and then shaped over time by the federal government’s response to successive court rulings regarding reasonable access. Today, medical cannabis falls within the purview of the Access to Cannabis for Medical Purposes Regulations (ACMPR).

In formulating our recommendations, we considered various aspects of access, including affordability, strains, potency, quality and adequacy of supply. We deliberated on the fundamental question of whether Canada should have a single system or two parallel systems, including separate access for medical cannabis. We also considered the strengths and weaknesses of the country’s current medical cannabis system and regulations.

We considered the views and experiences of patients and their advocacy organizations, the medical community, other jurisdictions and the public. While opinions of stakeholders may differ on some key questions, there is consensus on the need for more research aimed at understanding, validating and approving cannabis-based medicines.

In our view, the outcomes of such research will be necessary to determine the need for and features of a separate system for cannabis for medical purposes. However, as the new regulatory regime is established, it is important that the federal government continue to provide patients with reasonable access to cannabis for medical purposes, while contributing to the integrity of the overall cannabis regime and minimizing the potential for abuse and diversion.

To this end, the Task Force recommends that the federal government:

- Maintain a separate medical access framework to support patients

- Monitor and evaluate patients’ reasonable access to cannabis for medical purposes through the implementation of the new system, with action as required to ensure that the market provides reasonable affordability and availability and that regulations provide authority for measures that may be needed to address access issues

- Review the role of designated persons under the ACMPR with the objective of eliminating this category of producer

- Apply the same tax system for medical and non-medical cannabis products

- Promote and support pre-clinical and clinical research on the use of cannabis and cannabinoids for medical purposes, with the aim of facilitating submissions of cannabis-based products for market authorization as drugs

- Support the development and dissemination of information and tools for the medical community and patients on the appropriate use of cannabis for medical purposes

- Evaluate the medical access framework in five years

Implementation

The successful implementation of a regulatory framework for cannabis will take time and require that governments meet a number of challenges with respect to capacity and infrastructure, oversight, co-ordination and communications.

Capacity: Canada’s governments will need to move swiftly to increase or create capacity in many areas relating to the production and sale of cannabis. Success requires federal leadership, co-ordination and investment in research and surveillance, laboratory testing, licensing and regulatory inspection, training for law enforcement and others, and the development of tools to increase capacity ahead of regulation.

Oversight: To be satisfied that the system is minimizing harms as intended, it will need close monitoring and rapid reporting of results in a number of areas, including regulatory compliance and population health.

Co-ordination: The federal, provincial, territorial, municipal and Indigenous governments will need to work together on information and data sharing and co-ordination of efforts to set up and monitor all of the components of the new system. The Task Force believes that Canada should prioritize engagement of Indigenous governments and representative organizations, as we heard from Indigenous leaders about their interest in their communities’ participation in the cannabis market.

Communications: We heard from other jurisdictions about the importance of communicating early, consistently and often with the general public. Youth and parents will need the facts about cannabis and its effects. Actors in the new system – including employers, educators, law enforcement, industry, health-care practitioners and others – will require information tailored to their specific roles.

To this end, the Task Force recommends that the federal government:

- Take a leadership role to ensure that capacity is developed among all levels of government prior to the start of the regulatory regime

- Build capacity in key areas, including laboratory testing, licensing and inspection, and training

- Build upon existing and new organizations to develop and co-ordinate national research and surveillance activities

- Provide funding for research, surveillance and monitoring activities

- Establish a surveillance and monitoring system, including baseline data, for the new system

- Ensure timely evaluation and reporting of results

- Mandate a program evaluation every five years to determine whether the system is meeting its objectives

- Report on the progress of the system to Canadians

- Take a leadership role in the co-ordination of governments and other stakeholders to ensure the successful implementation of the new system

- Engage with Indigenous governments and representative organizations to explore opportunities for their participation in the cannabis market

- Provide Canadians with the information they need to understand the regulated system

- Provide Canadians with facts about cannabis and its effects

- Provide specific information and guidance to the different groups involved in the regulated cannabis market

- Engage with Indigenous communities and Elders to develop targeted and culturally appropriate communications

- Ensure that Canada shares its lessons and experience with the international community

These recommendations, taken together, present a new system of regulatory safeguards for legal access to cannabis that aim to better protect health and to enhance public safety. Their successful implementation requires the engagement and collaboration of a wide range of stakeholders. We believe that Canada is well-positioned to undertake the complex task of legalizing and regulating cannabis carefully and safely.

Chapter 1: Introduction

We begin our report by thanking those Canadians, experts, youth, Indigenous leaders, Elders, stakeholder organizations, government representatives, researchers, advocates, and patients, who took the time to participate in this consultation. Your views, advice and experiences have been insightful and invaluable.

We are thankful for the counsel provided by Mr. Bill Blair, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Justice, who served as Government liaison to the Task Force.

We are also grateful for the assistance and support provided by the federal Cannabis Legalization and Regulation Secretariat in helping us fulfill our mandate. Their continuous help with logistics, research, and communications gave us the freedom to focus on the content and meaning of the input received. We note our gratitude for the briefings provided by federal, provincial and territorial government officials to help guide our work. We would also like to note our appreciation for the support provided by the Canadian Consulates General in the states of Colorado and Washington during our study tours. Finally, we would like to thank Hill+Knowlton Strategies for their assistance in analyzing and synthesizing the nearly 30,000 submissions to the online questionnaire.

Our mandate

On June 30, 2016, the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, and the Minister of Health announced the creation of a Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation (“the Task Force”). Comprised of nine Canadians of varied experience and backgrounds, the Task Force was given a mandate to consult and provide advice to the Government of Canada on the design of a new legislative and regulatory framework for legal access to cannabis, consistent with the Government’s commitment to “legalize, regulate, and restrict access” as set out in its December 2015 Speech from the Throne.

In carrying out this mandate, we were asked to engage with provincial, territorial and municipal governments, Indigenous governments and representative organizations, youth, patients and experts in relevant fields, including but not limited to: public health, substance use, criminal justice, law enforcement, economics and industry and those groups with expertise in production, distribution and sales of cannabis. The initial questions that formed the core of our consultations were elaborated for us in a Discussion Paper prepared by the Government, entitled “Toward the Legalization, Regulation and Restriction of Access to Marijuana” (Annex 4). This document proved to be a valuable resource in framing our early thinking, questions, and deliberations, as well as a stimulus for the thoughtful input we sought and received.

This report summarizes the views shared with the Task Force throughout our engagement activities and presents advice on a new system for regulated access to cannabis, responding to our mandate, the questions set out in the Discussion Paper and the issues that arose during our consultations.

The Canadian context

This Task Force report follows in the footsteps of earlier parliamentary exercises over the last 35 years that have considered questions regarding cannabis law reform in Canada: notably, in the early 1970s, the Commission of Inquiry into the Non-medical Use of Drugs (the Le Dain Commission); in 1996, the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs; and, in 2002, the Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs. The reports published by these committees provided detailed analyses and recommendations that remain relevant today.

Canada has significant experience with cannabis use and cultivation. Despite the existence of serious criminal penalties for possessing, producing, and selling cannabis (cannabis possession offences account for half of all police-reported drug charges – 49,577 of 96,423 total in 2015), the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey from 2015 found that 10% of adult Canadians (25 years and older) report having used cannabis at least once in the past year and over one-third reported using cannabis at least once in their lifetime. Additionally, Canadian youth are more likely to consume cannabis (in the past year, 21% of those aged 15-19, and 30% of those aged 20-24) than adult Canadians or their peers worldwide. In view of these statistics, it is unsurprising that cannabis is widely available throughout Canada and that a well-established cannabis market exists in Canada. Parallel to this illicit commercial market is a “cannabis culture,” which is a widespread and deep rooted network that emphasizes the social and cultural aspects of cannabis use and the sharing of information on its cultivation.

Canada’s experience with legal cannabis regulation can be attributed, at least in part, to successive court decisions over recent years which resulted in the evolution of a framework of legal access to cannabis for medical purposes. This model has evolved over the past two decades, from one that initially provided individual exemptions to enable medical patients to possess cannabis for their personal consumption, to a system of federal licensure that allows patients, with the support of their physicians, to obtain cannabis from a licensed producer, to cultivate their own cannabis, or to designate someone to cultivate it on their behalf. Taken together, our experiences with these approaches have enabled the establishment of a system of cannabis production and sale that informs our thinking around the regulation of cannabis for non-medical purposes.

A sophisticated commercial industry that cultivates and distributes cannabis by mail and courier to individuals who require it for medical purposes, and who are under the care of a physician or nurse practitioner, exists in Canada today, with 36 licensed producers in operation at the time of writing this report. This new industry operates under the authority of federal regulations (Access to Cannabis for Medical Purposes Regulations) which set out product quality control measures and strict security standards to protect public health and safety. Task Force members had the opportunity to visit some of these producers and were impressed by the sophistication and quality of their work.

Operating in parallel to this federally regulated system of commercial producers is a complex and varied illicit market.

There are those who operate complex organized criminal enterprises who engage in violence and pose a threat to the public safety and well-being of Canadians. Globally, organized criminal groups reap large profits from the proceeds of cannabis production and trafficking. Canada is an exporter of cannabis for global illicit markets.

There are also those who seek to exploit a period of transition wherein the Government has made clear its intent to change the laws but during which existing laws prohibiting illicit production and sale continue to apply. A lack of understanding among members of the public about what is and is not permitted during this period of transition has led to confusion that has contributed to the establishment and proliferation of illegal activities.

A network of cannabis growers, consumers and advocates who engage in an underground economy of cannabis cultivation and sale for compassionate reasons also exists. While these activities are in violation of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) Footnote1, some cannabis stores (“dispensaries”) and wellness clinics (“compassion clubs”) have nevertheless been in operation for many years in parts of the country. The Task Force heard from several members of, and advocates for, this community who report developing and adhering to a strict internal code of standards, closely resembling self-regulation, and who wish to differentiate themselves from solely profit-driven, illicit enterprises.

A global perspective

Canada is one of more than 185 Parties to three United Nations drug control conventions: the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (as amended by the 1972 protocol), the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances and the 1988 Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances.

Despite enforcement efforts under these treaties, cannabis remains the most widely used illicit drug in the world. Although the ultimate aim of the drug treaties is to ensure the “health and welfare of humankind,” there is growing recognition that cannabis prohibition has proven to be an ineffective strategy for reducing individual or social harms, including decreasing burdens on criminal justice systems, limiting negative social and public health impacts, and minimizing the entrenchment of illicit markets, which in some cases support organized crime and violence. Thus, a growing number of governments are interested in alternative approaches to cannabis control that promote and protect the health, safety and human rights of their populations. Several European and Latin American countries have decriminalized the personal possession of cannabis.

This global shift in approaches to controlling and minimizing the harms associated with cannabis use has, for some, gone further. In 2013, Uruguay became the first country to enact legislation to legalize and regulate cannabis for non-medical purposes. At the sub-national level, following the United States [U.S.] federal election on November 8, 2016, a total of eight U.S. states – Alaska, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, Oregon and Washington – and the District of Columbia – have now voted to legalize and regulate cannabis for non-medical purposes. These states represent more than 20% of the total U.S. population (approximately 75 million people).

While it is not part of the Task Force’s mandate to make recommendations to the Government on how to address its international commitments, it is our view that Canada’s proposal to legalize cannabis shares the objectives agreed to by member states in multilateral declarations, namely: to protect vulnerable citizens, particularly youth; to implement evidence-based policy; and to put public health, safety and welfare at the heart of a balanced approach to treaty implementation.

Important lessons will undoubtedly arise from Canada’s experience in the coming years, ones that will be valuable for advancing the global dialogue on innovative strategies for drug control. We believe that Canada will remain a committed international partner by monitoring and evaluating our evolving cannabis policy and sharing these important lessons with national and international stakeholders.

Setting the frame

The mandate entrusted to us was to design a framework with new rules that would define and set the parameters for how Canadians access cannabis in the future.

Defining the terms

Legalization and regulation must be distinguished from “decriminalization,” as the terms are easily confused. Generally, decriminalization is referred to as removing criminal sanctions for some offences, usually simple possession, and replacing them with https://e4njohordzs.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tnw8sVO3j-2.pngistrative sanctions, such as fines. This maintains the illegality of cannabis but prevents individuals from acquiring a criminal record for simple possession. With decriminalization the production Footnote2, distribution and sale of cannabis remain criminal activities. Thus, individuals remain subject to the potential dangers of untested cannabis. Criminal organizations continue to play the role of producer, distributor and seller, thereby increasing risk, particularly to vulnerable populations.

Cannabis versus marijuana

The word “marijuana” is a common term used most often in reference to the dried flowers and leaves of the cannabis plant. It is a slang term that is not scientifically precise. We believe it is more appropriate to use the term cannabis when engaging in a serious discussion of the goals and features of a new regulatory system for legal access.

Indeed, Cannabis sativa is the botanical name for this ubiquitous herbaceous plant, which includes the drug type (“marijuana”) as well as industrial hemp.

Public policy objectives

The Honourable Jane Philpott, Minister of Health, during her plenary statement for the Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly on the World Drug Problem, outlined that “our approach to drugs must be comprehensive, collaborative and compassionate. It must respect human rights while promoting shared responsibility.” Footnote3

In moving ahead with its commitment to legalize, regulate and restrict access to cannabis, the Government set out its principal objectives in its Discussion Paper. These objectives were established to:

- Protect young Canadians by keeping cannabis out of the hands of children and youth;

- Keep profits out of the hands of criminals, particularly organized crime;

- Reduce the burdens on police and the justice system associated with simple possession of cannabis offences;

- Prevent Canadians from entering the criminal justice system and receiving criminal records for simple cannabis possession offences;

- Protect public health and safety by strengthening, where appropriate, laws and enforcement measures that deter and punish more serious cannabis offences, particularly selling and distributing to children and youth, selling outside of the regulatory framework, and operating a motor vehicle while under the influence of cannabis;

- Ensure Canadians are well-informed through sustained and appropriate public health campaigns and, for youth in particular, ensure that risks are understood;

- Establish and enforce a strict system of production, distribution and sales, taking a public health approach, with regulation of quality and safety (e.g., child-proof packaging, warning labels), restriction of access, and application of taxes, with programmatic support for addiction treatment, mental health support and education programs;

- Provide access to quality-controlled cannabis for medical purposes consistent with federal policy and court decisions;

- Enable ongoing data collection, including gathering baseline data, to monitor the impact of the new framework.

Paramount among these objectives are those intended to keep cannabis out of the hands of children and youth and to keep profits out of the hands of organized crime. Many have remarked that there is an inherent tension between these objectives. On the one hand, establishing a system with adequate protections that would seek to curb access to cannabis by youth suggests adopting a more restrictive model with numerous controls and safeguards, such as establishing higher age limits, adapting pricing strategies to discourage consumption, and imposing limitations to minimize promotion and commercialization. On the other hand, seeking to displace the illicit cannabis market requires the establishment of a legal market that is competitive with the existing illicit market, including safe and reasonable access, price, variety of product choice and adequate consumer education. Therefore, excessive restrictions could lead to the re-entrenchment of the illicit market. Conversely, inadequate restrictions could lead to an unfettered and potentially harmful legal market. Both extremes jeopardize the viability of the new system for cannabis.

The different approaches to regulating popular, yet potentially harmful and addictive, substances are well illustrated by how Canadian society has, over several decades, approached tobacco and alcohol. In this time, tobacco has moved from being heavily marketed to being highly restricted, whereas alcohol has moved from being strictly controlled to being widely available and promoted.

We were told on many occasions that we need to find a balance for cannabis. The diagram in Figure 1 below helps to illustrate the spectrum of options shown against a curve of potential harms, where at one end prohibition leads to thriving criminal markets and at the other unregulated, legal free markets lead to unrestrained commercialization. At both extremes, there exist social and health harms that most Canadians would find unacceptable.

At the bottom of the curve lies the balance we are seeking with regard to cannabis: the point on the continuum where the public policy goals set out by the Government are most likely to be achieved.

Figure 1 Footnote4 A spectrum of options

Figure 1 description

In seeking this balance, we believe that it is necessary to adopt a public health approach. As such, our recommendations are shaped by our view that the decisions taken in determining the precise features of this new regulatory system should uphold and promote the health of Canadians while reducing harms. In our discussions with experts, governments and others, strong support emerged for this public health approach, which includes:

- A focus on reducing harm and promoting health at the population level;

- Targeted interventions for high-risk individuals and practices;

- A concern with fairness;

- An evidence-based approach.

While it is well within the authority of governments to choose to apply taxes, to collect appropriate licensing fees and to establish cost-recovery systems, it is also our view that revenue generation should be a secondary consideration for all governments, with the protection and promotion of public health and safety as the primary goals.

Our advice is informed by the available evidence

Ideally, all of our recommendations would be based on clear, well-documented evidence. However, we recognize that cannabis policy, in its many dimensions, lacks comprehensive, high-quality research in many areas. On many issues throughout our discussions and deliberations, we have found that evidence is often non-existent, incomplete or inconclusive.

Being mindful of these limitations is imperative. It is more appropriate to refer to our recommendations as “evidence-informed” rather than “evidence-based”, given that the relationship between evidence and policy is complex and that our recommendations were influenced by the concerns, priorities and values expressed by stakeholders and members of the public, as well as by the available scientific evidence.

Moreover, a clear reality underpins our discussions and deliberations: encouraging and enabling more research and ensuring systematic monitoring, evaluation and reporting on our experiences is essential to good public policy in this area.

Some of these concepts are explored in greater detail in the section below, which describes the guiding principles behind our advice.

Engagement process

Fulfilling our mandate required that we seek as many views as possible from a diverse and informed community of experts, professionals, advocates, front-line workers, policy makers, government officials, patients, citizens and employers in the time provided to us. With this in mind, early in our work we identified a strategy for engagement that would rely upon various methods and means to reach out to Canadians and hear their views:

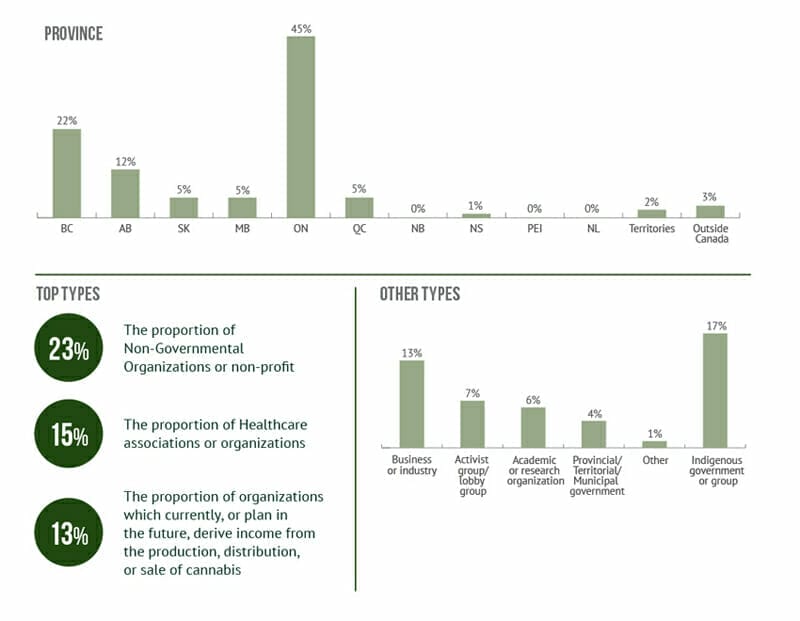

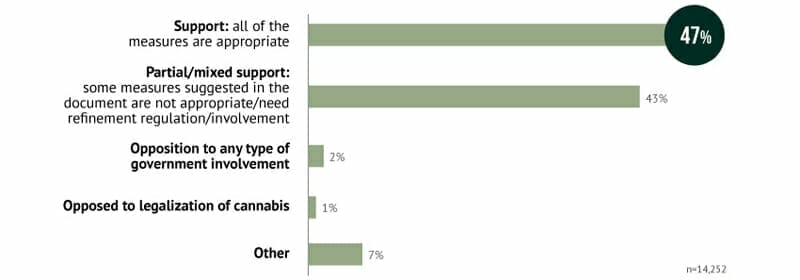

- Canadians: An online portal was open to the public for 60 days throughout July and August of 2016 and received nearly 30,000 submissions to the questions posed. Demographic information on the respondents is set out in Annex 5. The number of responses we received is clear evidence that many Canadians hold strong views on this subject, and we benefitted greatly from their collective views and advice. Hill+Knowlton Strategies assisted the Task Force in its analysis and synthesis of the responses. A summary of its report is included in Annex 5.Moreover, nearly 300 written submissions were submitted to the Task Force from various organizations. These submissions were often comprehensive presentations of the main issues of concern. A complete list of all the organizations and individuals who provided submissions is included in Annex 3.

- Governments: A key requirement in our mandate was to engage with provincial and territorial governments. We travelled to most provincial capital cities and to the North where we met with government officials representing multiple sectors and ministries. We participated in candid discussions and gained a clearer understanding of the diverse regional realities that will influence public policy in this area.

- Experts: We hosted a series of roundtable discussions in cities across the country, in order to engage with experts from a wide spectrum of disciplines, researchers and academics, patients and their advocates, cannabis consumers, chiefs of police and fire departments, and other municipal and local government officials, as well as numerous industry, professional, health and other associations.

- Indigenous peoples: Indigenous experts, representative organizations, governments and Elders were invited to participate in a variety of Task Force engagement activities, including in the expert roundtables, bilateral meetings and an Indigenous peoples roundtable. These opportunities provided the Task Force with valuable perspectives and a better understanding of the interests and concerns of First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities.

- Youth: Youth are at the centre of the Government’s objectives in pursuing a new system of regulated legal access to cannabis. Their voices were therefore essential. The Task Force sought to engage youth by including them and youth-serving organizations in expert roundtables and by hosting a youth-focused roundtable. The Task Force would also like to acknowledge Canadian Students for Sensible Drug Policy for their work in convening a youth roundtable event as a direct contribution to the Task Force’s youth engagement activities.

- Patients: Access to cannabis for medical purposes is a major preoccupation for many Canadian patients, their families, caregivers and health-care providers. The emergence of a regulatory framework for non-medical cannabis access was seen by many to be a challenge to medical cannabis access, products and research. We are grateful to Canadians for Fair Access to Medical Marijuana, the Arthritis Society, the Canadian AIDS Society, and the British Columbia Compassion Club Society for helping to facilitate a roundtable for patients.

- Study tours: In order to learn first-hand from those who have legalized cannabis, the Task Force conducted site visits to Colorado and Washington states. We were hosted by state officials and we participated in a range of briefings, meetings and site visits. Similarly, senior officials from the Government of Uruguay provided a detailed briefing to the Task Force regarding Uruguay’s unique experience as the only country to date to have enacted a regulatory system for legal access to cannabis.

The Task Force visited some of Canada’s licensed producers of cannabis, in order to understand the realities of regulated cannabis production in Canada. We also visited the B. C. Compassion Club Society, in order to learn from its experience of providing cannabis in a holistic, wellness-centered environment to patients in Vancouver for the last two decades.

The Task Force acknowledges that we were not able to hear from everyone who wished to offer their views. However, we are confident that we heard a diversity of views on the central issues in question. Our advice in this report is informed, and shaped, by the perspectives, knowledge and experiences shared with us by so many. A list of persons and organizations consulted can be found in Annex 3.

Guiding principles

Given the complexity of the issues, the Task Force set out a series of guiding principles and values that we see as important building blocks for our recommendations. The following principles and values have been validated throughout our consultations:

- Protection of public health and safety as the primary goal of the new regulatory framework, which includes minimizing harms and maximizing benefits;

- Compassion for vulnerable members of society and patients who rely on access to cannabis for medical purposes;

- Fairness in avoiding disproportionate or unjustified burdens to particular groups or members of society and in avoiding barriers to participation in the new framework;

- Collaboration in the design, implementation, and evaluation of the new framework, including communication and collaboration among all levels of government and with members of the international community;

- Commitment to evidence-informed policy and to research, innovation, and knowledge exchange;

- Flexibility in implementing the new framework, acknowledging that there is much we do not know and much that we will learn over time.

Chapter 2: Minimizing Harms of Use

Introduction: a public health approach

In taking a public health approach to the regulation of cannabis, the Task Force proposes measures that will maintain and improve the health of Canadians by minimizing the harms associated with cannabis use.

Most of the measures we propose seek to minimize harms in the population as a whole. We also consider more targeted means to minimize the harm to individuals, particularly children, youth and other vulnerable populations. A discussion of the harms associated with cannabis-impaired driving can be found in Chapter 4, Enforcing Public Safety and Protection.

Based on evidence that the risks of cannabis are higher with early age of initiation and/or high frequency of use, the Task Force proposes a public health approach that aims to:

- Delay the age of the initiation of cannabis use;

- Reduce the frequency of use;

- Reduce higher-risk use;

- Reduce problematic use and dependence;

- Expand access to treatment and prevention programs; and,

- Ensure early and sustained public education and awareness.

Cannabis: the essentials

Cannabis sativa is a plant that is used for its psychoactive and therapeutic effects and, like all psychoactive and therapeutic substances, carries certain risks to human health. Cannabis contains hundreds of chemical substances and more than 100 cannabinoids, which are compounds traditionally associated with the cannabis plant. Among these, two cannabinoids have received the most scientific interest: delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC has therapeutic effects and is the compound chiefly responsible for the psychoactive effects of cannabis, while CBD has potential therapeutic but no obvious psychoactive effects. The effects of cannabis are due to the actions of its cannabinoids on biological “targets,” a system of specific receptors and molecules found throughout the human body, together called the endocannabinoid system. The current science also suggests that other compounds in cannabis, such as aromatic terpenes and flavonoids, may also have pharmacological properties alone or in combination with the cannabinoids.

Assessing the risks

Risk is inherent in all discussions on the health effects of cannabis, yet our understanding of risk is constrained by more than 90 years of prohibition, which has limited our ability to fully study cannabis.

We know more about the short-term effects of cannabis use (e.g., psychoactive effects and effects on memory, attention and psychomotor function). We are less certain about some of the longer-term effects (e.g., risks of permanent harms to mental functioning and risks of depression and anxiety disorders) but more certain about others (e.g., dependence). The following is a snapshot of the risks of harms associated with cannabis use:

- Risks to children and youth: Generally speaking, studies have consistently found that the earlier cannabis use begins and the more frequently and longer it is used, the greater the risk of potential developmental harms, some of which may be long-lasting or permanent.

- Risks associated with consumption: Certain factors are associated with an increased risk of harms, including frequent use and use of higher potency products. Driving while impaired by cannabis is associated with an increased risk of accidents and fatalities. Co-use with alcohol may pose an incremental risk for impaired driving and co-use with tobacco may increase smoking-related lung disease.

- Risks to vulnerable populations: Studies have found associations between frequent cannabis use and certain mental illnesses (e.g., schizophrenia and psychosis) and between frequent cannabis use during pregnancy and certain adverse cognitive and behavioural outcomes in children.

- Risks related to interactions with the illicit market: These include violence and the risks associated with unsafe products, illicit production and exposure to other, more harmful illicit substances.

As noted in Chapter 1, in addressing these risks we are sometimes faced with trade-offs when choosing among different regulatory approaches, since reducing some risks could result in increasing others. We often turned to our guiding principles to help us make difficult choices.

In our roundtable discussions and throughout the submissions we received, stakeholders often noted that, alongside the risks of use, there are also benefits, including for relaxation purposes, as a sleep aid or for pleasure. Notably, there is emerging evidence with regard to the use of cannabis as an alternative to more harmful substances, suggesting a potential for harm reduction (see also Chapter 5, Medical Access). The Task Force agrees that further research should be a priority.

Learning from the regulation of tobacco and alcohol

In assessing the measures presented in this chapter, at times comparisons are made with the ways alcohol and tobacco are regulated. In some ways the substances are comparable, being associated with factors such as impairment, dependence, health harms and widespread use. However, there are important differences in risks, social and health impact, and prevalence of use.

The 2009 World Health Organization (WHO) ranking of leading global risk factors for disease includes alcohol (ranked 3rd) and tobacco (6th). Notably, it does not include cannabis. In comparing levels of risk, it is important to consider patterns of use and the high global prevalence of alcohol and tobacco use. As well, years of research data collection and evaluation have provided information on the individual and societal impacts of alcohol and tobacco use that is not yet available for cannabis. Nevertheless, the Task Force acknowledges that, based on current levels of use and available information on mortality and morbidity, the harms associated with the use of tobacco or alcohol are greater than those associated with the use of cannabis.

In this report we recommend a series of measures that are, in some cases, stricter than those that exist for tobacco or alcohol in Canada. Given the relative harms, we acknowledge this contradiction but believe that the regulation of these substances has been inconsistent with WHO disease risk ranking and remains inconsistent with known potential for harm. In designing a regulatory system for cannabis, we have an opportunity to avoid similar pitfalls.

The Task Force recognizes that the regulatory regimes for alcohol and tobacco continue to evolve. It is our hope that our experience with cannabis regulation will be used to inform the further evolution of alcohol and tobacco regulations.

Minimum age

Setting a minimum age for the purchase of cannabis is an important requirement for the new system. The age at which to set the limit was the subject of much discussion and analysis throughout our deliberations.

As with many of the other measures discussed in this chapter, a minimum age is intended to support the Government’s objective to protect children and youth from the potential adverse health effects of cannabis by putting in place safeguards that better control access. In Canada, minimum ages for alcohol and tobacco sales have been set by the federal government (for tobacco) and by the provinces and territories (for both substances). Some have set the legal age for purchase at 18, others at 19. However, we know that age restrictions on their own will not dissuade youth use; other complementary actions – including prevention, education, and treatment – are required to achieve this objective.

What we heard

The Task Force heard broad support for establishing a minimum age for the sale of cannabis. However, the youth with whom we spoke did not believe that setting a minimum age alone would prevent their peers from using cannabis.

Some health experts argued that there was no clear scientific evidence to identify a “safe” age of consumption, but agreed that having a minimum age would reduce harm. There was a general recognition that a minimum age for cannabis use would have value as a “societal marker,” establishing cannabis use as an activity for adults only, at an age at which responsible and individual decision-making is expected and respected.

We heard from many participants that setting the minimum age too high risked preserving the illicit market, particularly since the highest rates of use are in the 18 to 24 age range. A minimum age that was too high also raised concerns of further criminalization of youth, depending on the approach to enforcement.

Ages 18, 19 and 21 were most often suggested as potential minimum ages. Health-care professionals and public health experts tend to favour a minimum age of 21. A minimum age of 25, often cited as the age at which brain development has stabilized, was generally viewed as unrealistic because it would leave much of the illicit market intact. In U.S. states where cannabis is legal, governments have aligned the minimum age at 21 for alcohol and cannabis consumption.

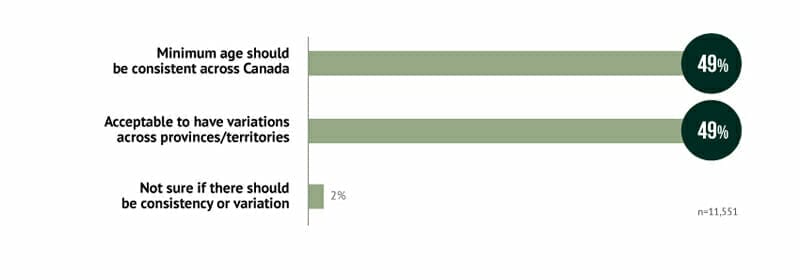

There was considerable discussion regarding the importance of national consistency. Having the same minimum age for purchase in all provinces and territories was thought to mitigate problems associated with “border shopping” by youth seeking to purchase cannabis in a neighbouring province or territory where the age is lower. In this regard, we heard suggestions that governments could learn from the challenges associated with alcohol age limits, which are inconsistent across the country. A range of public health and other experts recommended that the federal government set the minimum age, and that the provinces and territories be able to raise the age but not lower it.

Others argued that, for the sake of clarity and symmetry, the minimum age for purchasing cannabis should be aligned with the current provincial and territorial ages for sales of alcohol and tobacco. Many suggested that 18 was a well-established milestone in Canadian society marking adulthood.

Considerations

Research suggests that cannabis use during adolescence may be associated with effects on the development of the brain. Use before a certain age comes with increased risk. Yet current science is not definitive on a safe age for cannabis use, so science alone cannot be relied upon to determine the age of lawful purchase.

Recognizing that persons under the age of 25 represent the segment of the population most likely to consume cannabis and to be charged with a cannabis possession offence, and in view of the Government’s intention to move away from a system that criminalizes the use of cannabis, it is important in setting a minimum age that we do not disadvantage this population.

There was broad agreement among participants and the Task Force that setting the bar for legal access too high could result in a range of unintended consequences, such as leading those consumers to continue to purchase cannabis on the illicit market.

For these reasons, the Task Force is of the view that the federal government should set a minimum age of 18 for the legal sale of cannabis, leaving it to provinces and territories to set a higher minimum age should they wish to do so.

To mitigate harms between the ages of 18 and 25, a period of continued brain development, governments should do all that they can to discourage and delay cannabis use. Robust preventive measures, including advertising restrictions and public education, all of which are addressed later in this chapter, are seen as key to discouraging use by this age group.

For many in the legal and law enforcement fields, the key issue is not the minimum age itself but the implications for those who ignore it, including those who sell to children and youth, and those under the minimum age who possess and use cannabis. These are addressed in Chapter 4, Enforcing Public Safety and Protection.

Advice to Ministers

The Task Force recommends that the federal government set a national minimum age of purchase of 18, acknowledging the right of provinces and territories to harmonize it with their minimum age of purchase of alcohol.

Promotion, advertising and marketing restrictions

In designing a system for the regulation of cannabis, we are creating a new industry. As with other industries, this new cannabis industry will seek to increase its profits and expand its market, including through the use of advertising and promotion. Because of the risks discussed earlier in this chapter, regulation aims to discourage use among youth and ensure that only evidence-informed information is provided to adults. Restrictions on advertising, promotion and related activities are therefore necessary.

Our society’s experience with the promotion of tobacco and alcohol is instructive, since the promotion of these products is recognized as an important driver of consumption and of the associated harms. In response, many governments have restricted how tobacco and alcohol may be promoted. In Canada, there are different approaches to each.

The federal Tobacco Act restricts the promotion of tobacco products, except in limited circumstances. It also specifically prohibits promotion by means of a testimonial or endorsement, false or misleading advertising, sponsorship promotion, lifestyle advertising (which evokes images of glamour, excitement, and risk) and advertising appealing to young people.

Advertising that promotes a tobacco product by describing brand characteristics or providing information (factual information about a product and its characteristics, availability or price) are permitted in limited circumstances, such as in publications and in locations not accessible to young people. Provincial and territorial laws also set stringent limits on promotion of tobacco products.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s Code for Broadcast Advertising of Alcoholic Beverages includes federal restrictions on the promotion of alcohol in radio and television broadcasting. It includes prohibitions on advertisements that appeal to minors, that encourage the general consumption of alcohol and that associate alcohol with social or personal achievement. Each province and territory also has its own rules restricting the promotion of alcohol. Despite regulations such as the advertising code, alcohol is heavily marketed and promoted to adults in Canada.

What we heard

In the Task Force’s consultations, the majority of health-care professionals, as well as public health, municipal, law enforcement and youth experts, believed there should be strict controls on advertising and marketing of cannabis. We heard that such restrictions would be necessary to counter the efforts by industry to promote consumption, particularly among youth. There were also concerns expressed that companies would market products to heavy users or encourage heavy use, and exploit any exceptions that are left open.

We heard strong support from, among others, educators, parents, youth and the public health community for comprehensive marketing restrictions for cannabis similar to those for tobacco. Such restrictions were considered to be necessary because the evidence from our experience with tobacco and alcohol suggests that partial restrictions send mixed messages about use.

Several public health stakeholders also recommended plain packaging for cannabis products, similar to the approach taken by Australia for tobacco products and which are soon to be applied to tobacco products in Canada. Plain packaging refers to packages without any distinctive or attractive features and with limits on how brand names are displayed (e.g., font type, colour and size).

The industry representatives from whom we heard, while generally supportive of some promotion restrictions – particularly marketing to children and youth, and restrictions on false or misleading advertising – made the case for allowing branding of products. It was suggested that brand differentiation would help consumers distinguish between licit and illicit sources of cannabis, helping to drive them to the legal market. As well, to achieve “brand loyalty,” companies would have the impetus to produce high-quality products and would be more accountable to their customers.

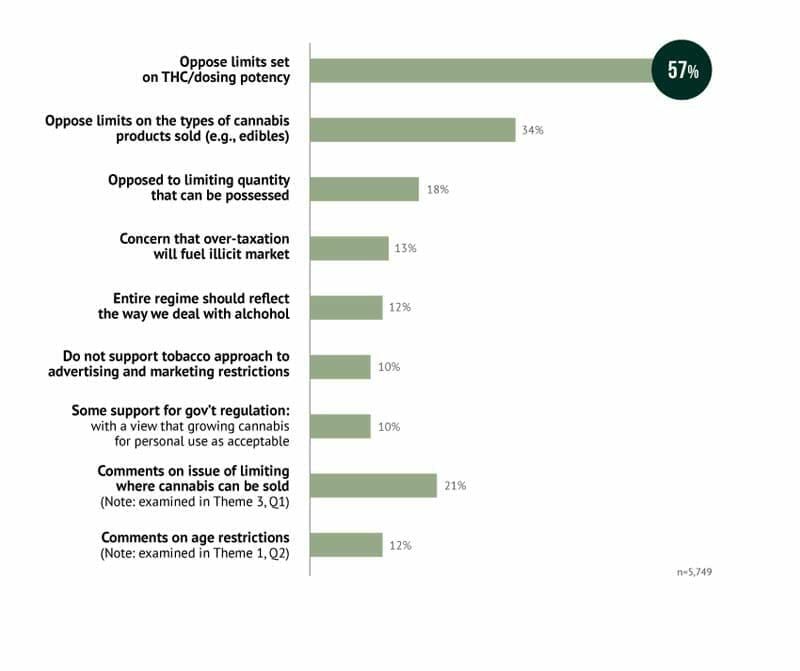

In our online consultation, some were opposed to tobacco-style advertising restrictions for cannabis because, in their opinion, cannabis is less harmful than either tobacco or alcohol.

For some online respondents, allowing in-store advertising for cannabis brands offered a potential compromise: youth would be protected from exposure to mass marketing and advertising, while producers and retailers could still engage and communicate with consumers of cannabis of legal age and in regulated environments.

Considerations

The Task Force agrees with the public health perspective that, in order to reduce youth access to cannabis, strict limits should be placed on its promotion. In our view, comprehensive restrictions similar to those created by tobacco regulation offer the best approach. There is also a concern that the presence of any cannabis promotion could work against youth education efforts.

The challenges with creating partial restrictions (i.e., only prohibiting advertising targeting youth) are well documented. In practice, it is difficult to separate marketing that is particularly appealing to youth from any other marketing. The Colorado officials with whom we met echoed this concern, noting that their partial restrictions for cannabis advertising made it challenging to avoid advertising that reaches, or is appealing to, youth.

A partial restriction focusing on marketing to youth becomes even more problematic if one considers the 19-to-25 age group; it will be legal for those in this age group to purchase, but the evidence of potential harm suggests that use within this group should be discouraged as a matter of health. Trying to prohibit marketing that is appealing to this age group compared to people in their late 20s or 30s would be impossible. The Task Force believes that, while there should be a federal minimum age of 18 for the reasons explained above, other policies, such as comprehensive marketing restrictions, will be needed to minimize harms to the 18-to-25 age group.

Comprehensive advertising restrictions should cover any medium, including print, broadcast, social media, branded merchandise, etc., and should apply to all cannabis products, including related accessories. Such restrictions could still leave room for promotion at the point of sale, which would answer industry concerns about allowing information to be provided to consumers and some branding to differentiate their products from the illicit market and other producers. This assumes that the point of sale is a retail outlet not accessible to minors (see Chapter 3, Establishing a Safe and Responsible Supply Chain); the Tobacco Act allows information and brand preference advertising in places where young persons are not permitted, and those provisions could be used as a model.

If branding were permitted, along with limited point-of-sale marketing and product information, we are concerned that this information would still make its way to environments where minors would be exposed and influenced, much as they are today by alcohol and tobacco brands. The Task Force feels there is sufficient justification at this time for plain packaging on cannabis products. Such packaging would include the company name, as well as important information for the consumer, including price and strain name, as well as any applicable labelling requirements (see the “Cannabis-based edibles and other products” and “THC potency” sections in this chapter).

Any promotion, marketing or branding that is allowed should still be subject to restrictions, such as lifestyle advertising (similar to the Tobacco Act restrictions), false or misleading promotion (as for food, drugs and any other consumer product), the encouragement of excessive consumption (similar to standards for alcohol) and therapeutic claims (similar to restrictions for drugs or natural health products in the Food and Drugs Act).

In setting restrictions, the federal government should consider options for oversight and enforcement. This should include effective oversight by government, possibly supplemented by industry self-regulation (as is the case with pharmaceuticals). Advice on the appropriate penalties for those companies that violate these requirements is outlined in Chapter 4.

Advice to Ministers

The Task Force recommends that the federal government:

- Apply comprehensive restrictions to the advertising and promotion of cannabis and related merchandise by any means, including sponsorship, endorsements and branding, similar to the restrictions on promotion of tobacco products

- Allow limited promotion in areas accessible by adults, similar to those restrictions under the Tobacco Act

- Require plain packaging for cannabis products that allows the following information on packages: company name, strain name, price, amounts of THC and CBD and warnings and other labelling requirements

- Impose strict sanctions on false or misleading promotion as well as promotion that encourages excessive consumption, where it is allowed

- Require that any therapeutic claims made in advertising conform to applicable legislation

- Resource and enable the detection and enforcement of advertising and marketing violations, including via traditional and social media

Cannabis-based edibles and other products

In observing the manner in which illicit and legal markets for cannabis have emerged and continue to evolve, it is clear that cannabis is a versatile raw material that can be used to make a wide variety of consumer, medicinal and industrial products. Extending far beyond the dried cannabis popularized in the 1960s and 1970s, today’s cannabis is available in a wide range of cannabis-infused foods, cooking oils and drinks (typically referred to as “edibles”), oils, ointments, tinctures, creams and concentrates (e.g., butane hash oil, resins, waxes, and “shatter”). These products can be made with different types of cannabis, with varying levels of THC and CBD, resulting in different intensities and effects. The net result is that any discussion about regulating a new cannabis industry quickly leads to an understanding of the complexity of regulating not one but potentially thousands of new cannabis-based products.

Under Canada’s current cannabis for medical purposes system, the Government permits only dried and fresh cannabis and cannabis oils. Although other cannabis products may not be sold, the regulations allow individuals to make edible products, such as baked goods, for their own consumption. Nevertheless, access to a broad range of cannabis products is possible via the illicit market, including through dispensaries and online retailers. Determining the extent to which the new regulatory system should enable or restrict the range of legally accessible cannabis products, both initially as well as over the longer term, and whether and how to limit the availability of cannabis and cannabis products with high levels of THC (see “THC potency,” later in this chapter) are critical issues.

Edible products have emerged as a focal point in our discussions, given their variety and increasing popularity, as well as their particular risks.

What we heard: Cannabis-based edibles

Since legalizing cannabis, the states of Colorado and Washington have seen sustained growth in their cannabis edibles markets. In Colorado, sales of cannabis-infused edibles in the first quarter of 2015 were up 134% from the same period in the previous year.

Colorado officials acknowledge that a lack of regulation around edibles in the early days of legalization led to some unintended public health consequences. Their experience provides the Task Force with a number of specific “lessons learned”:

- Expect edibles to have a broad appeal. Cannabis products such as brownies, cookies and high-end chocolates are attractive to novice users and those who do not want to smoke or inhale. Colorado’s prohibition on public smoking also gave a boost to the edibles market.