By James Kwantes

Resource Opportunities

Serendipity – the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way.

The German pilot who survived a remote plane crash and stayed alive during an Arctic winter by eating a dead passenger. A Yukon pioneer who joined the gold rush with her dad and still lived in the log cabin she and her husband had built in 1910. And a young baritone named Tom Woodward, aka Tom Jones, just before he became an international singing sensation.

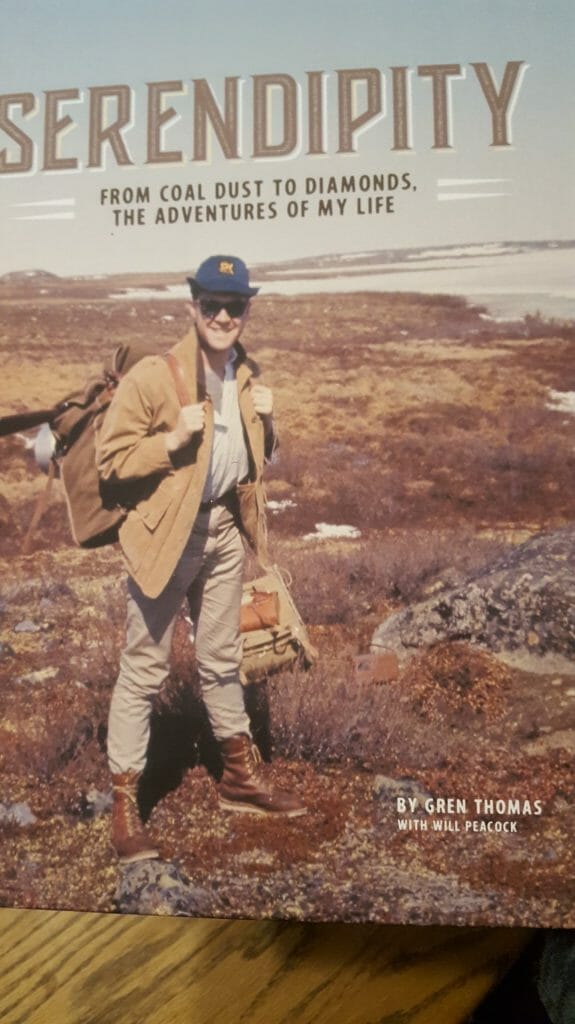

We meet each of these colourful characters and more in the pages of Gren Thomas’s memoir, Serendipity: From Coal Dust to Diamonds, the Adventures of My Life. Thomas left his native Wales for Canada in 1964 and quickly got bitten by the exploration bug. He spent much of the next 30 years bouncing around Canada’s North in helicopters and small planes, and living in remote exploration camps. In 1994, Thomas’s Aber Resources made the Diavik discovery, which became Canada’s second diamond mine.

BOOK GIVEAWAY: Sign up for Diamond Hands, the live North Arrow Minerals webinar on Tuesday, November 2, at 1 p.m. PST for a chance to win one of three signed copies of Gren Thomas’s book, Serendipity: From Coal Dust to Diamonds, the Adventures of My Life. Names will be drawn randomly from those who attend the webinar. North Arrow is processing a 2,000-tonne bulk sample from its Naujaat project, which has a population of rare orangey yellow diamonds.

A sense of wide-eyed wonder pervades Thomas’s book and it’s no surprise. As a young boy, he enjoyed reading books about faraway adventures, before his life became one. From playing cowboys and Indians with pals on the streets of small-town Wales to working closely with First Nations explorers in remote northern Canadian work camps.

The mining entrepreneur grew up in a working-class Welsh mining town. Men followed their fathers and grandfathers into the coal mines and steel mills and tinplate factories. Thomas’s rugby-playing father started working full-time at age 13. His grandfather had signed his dad’s birth certificate with an X.

Thomas’s fate diverted him to university in Cardiff (mining engineering), then to Canada. His first job was surveying underground at Falconbridge’s nickel mine in Sudbury, Ontario, followed by a gig at the Giant gold mine in Yellowknife. Then opportunity knocked.

The wife of a company exploration geologist had run off with the pizza boy, with the geologist in hot pursuit. The vacancy was filled by Thomas, who flew off to his first posting just south of Lac de Gras in the Northwest Territories. It’s now a storied diamond district but Thomas was prospecting for copper.

As he puts it on Page 5, “Things just happened to me. Luck, chance, serendipity — call it what you will — has always played a powerful role in my life. Not that I’m particularly lucky. But just as the three princes of Serendip would chance upon some fortunate happenstance, I would look for one thing and something else quite unexpected would arise.”

Serendipity is a very personal memoir, and the early years were pretty interesting, too. His was a “free range” childhood where getting home before dark was the primary consideration. He and his pals explored quarries, got into mischief and swam in the river. One of his neighbours, the Halls, had a daughter named Jeannie who used to play barefoot in the street as a young child. She later moved to England and married pro soccer player John Nash; their son is Canadian basketball superstar Steve Nash, the Vancouver Whitecaps co-owner and Brooklyn Nets coach.

In 1967, after the two mine gigs, Thomas and three friends went into the exploration business. Two of his partners were Irish and one was an Englishman, so they called the company Anglo Celtic Exploration. Yellowknife was their home base.

Thomas almost didn’t survive that first job. Anglo Celtic was hired by two Vancouver prospectors to stake claims in the remote Nahanni Valley, near the NWT-Yukon border. It was known as the Headless Valley because several prospectors had gone missing and their headless bodies found over the years.

Thomas and his crew flew in on a float plane and landed on the river; they were using two small helicopters to stake. One day, the pilot was preparing to land on the rocky ridge of a razorback high above the valley bottom when the helicopter stalled; the crash landing ripped off both pontoons. The helicopter teetered, then plunged over the edge and began descending to the valley floor. The pilot finally got the engine started and landed on a sandbar in the river.

The plane that was supposed to pick them up after the staking operation couldn’t land because the river was so full of ice. The crew crammed into the two small helicopters, with their gear, and set off through the canyon until it became too dark to fly. They landed on a sand spit and set up for the night. “We huddled that night under an old tarp pitched on the sand, lying there listening to the big ice floes crashing down the river on either side of us.”

The brush with death was a bit of foreshadowing. “Death, it seemed, was never very far away,” he writes. Thomas lost several friends and acquaintances in the North: to drowning, in plane crashes, to murder.

Geologically speaking, there were also plenty of close calls, as well as successes beyond diamonds. Thomas’s Highwood Resources discovered the Thor Lake rare earths deposit, now a feasibility-stage project (Nechalacho) being advanced by Avalon Advanced Materials. Thomas crossed paths with a fascinating cast of characters in the North. Some of the encounters were more consequential than others, of course.

“I met (Chuck) Fipke once in Yellowknife in 1991. I was in the bar of the Explorer Hotel with an English geologist friend, Nigel Hawthorn, and Nigel introduced us. At that time, I didn’t have a clue who he was. The bar was noisy, and Fipke seemed more interested in the stripper, who was gyrating halfheartedly around a pole, than in talking to me.

“That meeting was September 11, 1991. I didn’t know it then, but Fipke had hit the kimberlite motherlode two days earlier at Point Lake, and was on his way back to his Kelowna lab to analyze his samples. When he did, he found microdiamonds.

“The world for me — and the mining industry in Canada — was about to change.”

Fipke’s Dia Met discovery at Lac de Gras, announced in November 1991, set Thomas off on another adventure of a lifetime — one described in the book’s final chapter. Thomas’s group, already very familiar with the area, contacted South African diamond veteran Chris Jennings, who convinced them of the find’s significance. Jennings was in London and jumped on the next plane to Canada.

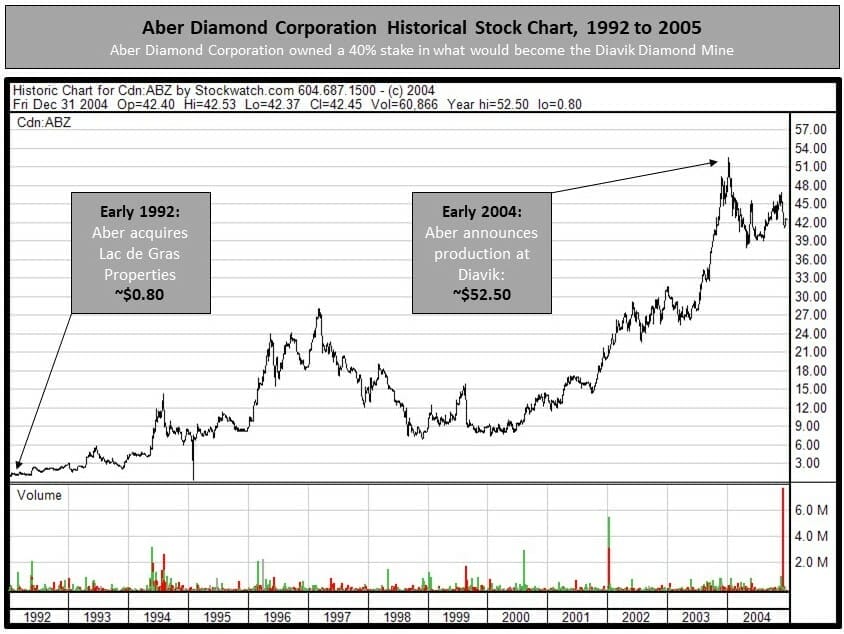

Speed and secrecy were critical. Thomas and Jennings flew to Yellowknife, separated at the airport and checked in at different motels. They staked well over a million acres of ground that winter, first movers in the world’s largest staking rush. Aber’s Diavik discovery came in the spring of 1994. Some of that ground remains in North Arrow Minerals’ property portfolio.

The Aber Diamond score made Thomas and Aber shareholders a pile of money. Some of his winnings went towards opening the Red Lion Bar & Grill, an old-style U.K. pub, in West Vancouver. It’s named for the pub where one of his grandmothers was born in his hometown of Morriston, Wales.

As for that first company Thomas incorporated, it still exists. Anglo Celtic is the holding company through which Thomas owns large stakes in North Arrow Minerals, B.C. gold play Westhaven Gold and U.K.-focused tin/copper play Cornish Metals.

North Arrow is now processing a partner-funded 2,000-tonne bulk kimberlite sample from its Naujaat project at the Saskatchewan Research Council lab in Saskatoon. The large diamond deposit, located on tidewater in Nunavut, hosts a distinct population of fancy, potentially high-value orangey yellow diamonds. The purpose of the bulk sample is to determine the size profile and quality of the coloured diamond population.

Thomas owns more than 12.9 million North Arrow shares, about 10.7% of the company. Other major shareholders are Lukas Lundin, Ross Beaty and Thomas Kaplan (through Electrum Strategic Opportunities Fund), each of whom own more than 9% of North Arrow’s outstanding shares.

Disclosure: James Kwantes was compensated for writing this article and owns shares of North Arrow Minerals and Westhaven Gold. This article is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as investment advice. All speculators need to do their own due diligence.