My friend asked me what my article was about this week.

I said options.

She said, what are the options?

I said, I wish I had some.

And this, my friends, is where we begin. Or rather, continue.

I have unwittingly delved into the world of options trading and it seems there is no way out; only through. Sort of like running but with leg weights and in water. And you all know how I feel about running.

I introduced all you beautiful people to the world of options here.

No surprise, options contracts aren’t actual physical pieces of paper (imagine how charming that would be though). It is all done electronically – just like everything else in life that shouldn’t be (i.e. shopping, working, dating, etc.). You can buy or sell an option contract with your brokerage account within a few seconds with the click of your “mouse” in the same way we can buy or sell regular stocks.

Without further ado, meet the option chain. All I can equate this to is how I feel about blockchain – which is to say, overwhelmed and almost offended. Although it looks like the electronic equivalent of 1000 tangled necklaces, an option chain is simply just a list of all the options we can trade. You can find this on any trading platform or sites such as Yahoo Finance/Google Finance – basically anywhere you can find a stock trading, options will be lurking not far behind.

Most companies have options available to trade.

So, you’ve gotten to the screen of tangled necklaces (option chains) and you click on a particular expiration date. A whole list of both call and put options will come up that, you guessed it, expire on that date.

In keeping with the theme of hell, there are a variety of different strike prices to choose from that are listed, for no particular reason, in ascending order (herein lies the chain element).

There is also, similarly to stocks, an ask price and a bid price.

- ASK price: lowest price a seller will accept at that moment (you buy at the ask price)

- BID price: highest price a buyer is willing to pay at that moment (you sell to the bid price)

If you’re out here looking to buy a call option, for example, you will have to pay the ask price.

(Or you can put in a lower bid and see if someone will agree to sell you the contract for that price – we love a haggle).

And to absolutely drill home this hellscape motif, it is of note that 1 option contract controls 100 shares of stock (no-one’s playing to just sell you one share). Because of this, option prices inherently come with a multiplier of 100.

Don’t think too hard on it. Basically, if you want to buy a call option and the ask price is 2.78… it will cost you $278. Just remove the decimal point to see what prices you’re working with.

Options prices are based on 3 elements:

1. Time to Expiration

All option contracts have expiration dates.

You don’t get to make a one-time payment and have insurance until kingdom come. You have to pay month by month, like a true adult, to stay insured (i.e., the longer you have insurance, the more money you will have paid over time). Options are the same.

An option with 60 days until expiration may cost you $500 (5.00).

Whereas an option with 30 days until expiration may cost $250 (2.50).

More time until expiry = More $ you’re paying.

So naturally, as time passes, an option’s time value will decay. This process is aptly referred to as, yes, “time decay”. As your option gets closer to its expiration date, time decay will rapidly speed up. The important take-away here is that an option’s time value is always decaying.This, unlike most things in options, is logical. Time decay accelerates as an option’s time to expiration draws closer since there’s less time to realize a profit from the trade.

Say that you need Apple stock to jump up $100 (that’s nearly double) by tomorrow (the expiration date of the option). Unless the company rolls out a hologram feature where your friends appear life-sized in front of you…the option will most likely expire worthless. So, today, due to time decay, that option is worth a whole lot less than it was when you bought it 30 days ago. (30 days ago, they had more time to figure out this hologram situation, and therefore it was much more plausible/likely the stock could rise in that amount of time).

P.S. $100 is a deeply unrealistic price rise in 30 days (save for the hologram, of course). I’m just out here being dramatic.

2. Underlying Stock Price

For each stock there are multiple options listed at different price increments (oh good, the chain is back). As we’ve learned (here), this is called the options “strike price” (i.e., the price at which the option contract can be exercised). The strike price of the option you are trading has a huge effect on what the option contract price will be.

Do NOT run screaming, (although that was my initial reaction as well).

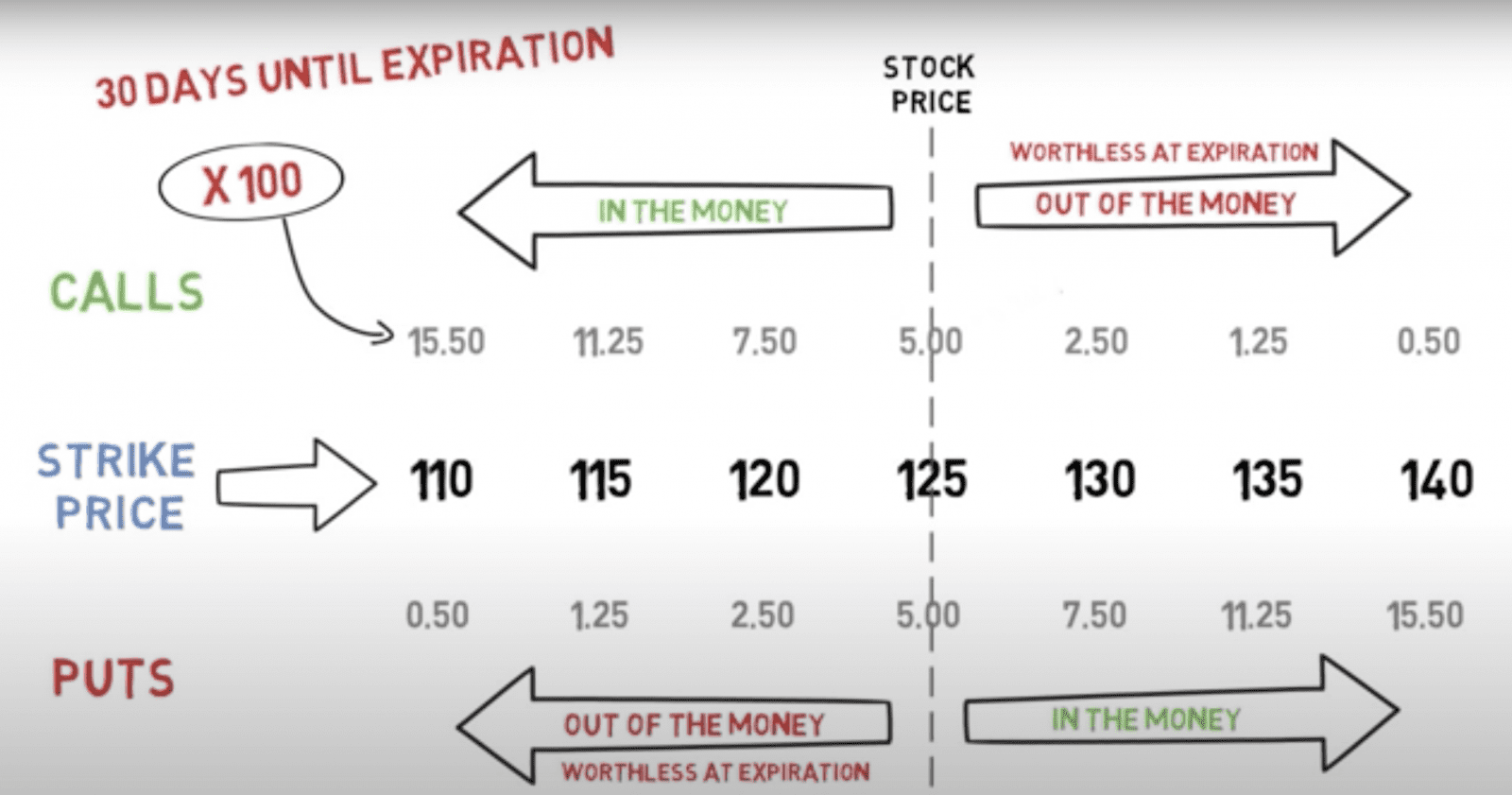

A visual with primary colors is necessary in times like these.

The stock right now is trading at 125. It is Apple. You are confident about the hologram thing. You say: Hey Apple girl, I love you, I believe in you, you are going to the moon (this is r/WallStreetBets lingo for thinking the stock price will climb very high – complete with the spaceship emoji).

So, you buy one call option for $50 at the strike price of 140. (Peep the little grey 0.50 above 140 and remember my remove the decimal rule – this is the ask price).

In human words, you think the stock is going to jump up (within the next 30 days) to be trading at $140 rather than its current $125. This is known as out of the money.

Others who don’t have your type of confidence in the hologram, may buy a call for 120 which will cost them a much heftier $750. This is known as in the money.

I love these terms. I think they are so finance chic. In options trading, the difference between “in the money” (ITM) and “out of the money” (OTM) is a matter of the strike price’s position relative to the market value of the underlying stock. An ITM option is one with a strike price that has already been surpassed by the current stock price. An OTM option is one that has a strike price that the underlying security has yet to reach.

(Don’t worry about the rest of this nonsense here with puts and what have you – I will be going through it in depth next week. All you need to know is that the underlying stock price and its movements affect the cost of an option).

3. Volatility

I have compared this concept to my sister in the past. It refers to the magnitude of a stock’s price swings. Higher volatility means bigger price swings and more risk for the investor who owns stock (the Behemoth rollercoaster as opposed to the Taxi Jam for any Canada’s Wonderland kids out there). In options, more risk = more $ (cost). Seems counterintuitive, no?

No. Let’s say you are providing life insurance to two different people. Person A is overweight, smokes a pack a day and has a heart condition. Person B is Ryan Reynolds (the image of health). Who do you think will have to pay more for life insurance? Obviously, not Ryan Reynolds.

So, think of “A” as a stock with high volatility and Ryan as a stock with low volatility.

You pay more for the thing that may cash in for you more – so, the cost of the option contract and premium is going to be higher. It has more potential to skyrocket or plummet just as Person A has more potential to die (and their spouse to then make use of that life insurance – I didn’t mean for this to come off as bleak as it has).

Let’s just keep swimming, or, at the very least, try not to drown.

Until next week…