Con artists make money through deception. They lie and cheat people into thinking they’re being let in on some great deal, or some easy money, when they’re the ones who’ll be making the money. If that doesn’t work, then they’ll poke at our insecurities, our loneliness, our need for validation. America’s favourite con is you can be successful if you just work harder.

But in America, a country that indoctrinates its citizens to believe that poverty is the province of the lazy and unmotivated, it’s remarkably easy to complete the con. That’s where Silicon Valley excels.

Their insidious ideological whisper campaigns reach you through trusted news sources promising potential futures full of freedom, choice and agency. Silicon Valley encompasses insights like these in terms like ‘gig economy,’ and invites you to quit your boring (but stable) traditional job in favour of the potential lucre you could be making working for one of their companies. After all, you can make your own schedule. You can set your own rate. You can be the master of your own destiny. And if you’re not one of those lucky enough to find one of those traditional jobs then the gig economy is there for you.

All you need to do to take advantage of this great opportunity, they say, is give up the traditional protections offered to employees—like like unemployment insurance, health care subsidies, paid parental leave, overtime pay, workers’ compensation, paid rest breaks, and a guaranteed $12 minimum hourly wage. And, perhaps more importantly, the ability to unionize.

Beyond Silicon Valley’s glossy promises and packaging, you’ll find the same labour exploitation war our grandparents and their unions fought, and the State of California is tired of it. That’s why they introduced Assembly Bill 5 (AB 5).

Last year, the California Supreme Court ruled that companies must apply a test to determine if a worker is an independent contractor. Using the ABC test, a company wouldn’t need to give a worker the protections of an employee if the worker:

(A) is free from the control and direction of the hirer in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of such work and in fact;

(B) performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business; and

(C) is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as the work performed for the hiring entity.

If AB 5 were to pass the Senate, it would force companies like Uber (UBER.NYSE) and Lyft (LYFT.Q) to reclassify their workers as full employees rather than expendable contractors.

Uber said that reclassifying its drivers as employees “would require us to fundamentally change our business model, and consequently have an adverse effect on our business and financial condition.”

Uber and Lyft’s counter-proposal includes offering benefits like paid time off, retirement planning and education reimbursement. Drivers could choose which perks they prefer, and coverage would be prorated based on how often drivers work.

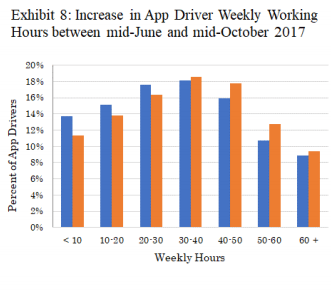

That would be a great if the majority of Uber and Lyft workers were, as the company states, part-timers trying to make a little extra cash. But a recent report published by the University of California Berkeley indicated that driving for ride-hailing apps in New York City was not a part-time gig for people. Instead, it was viewed as a full-time job by a heavy percentage of users.

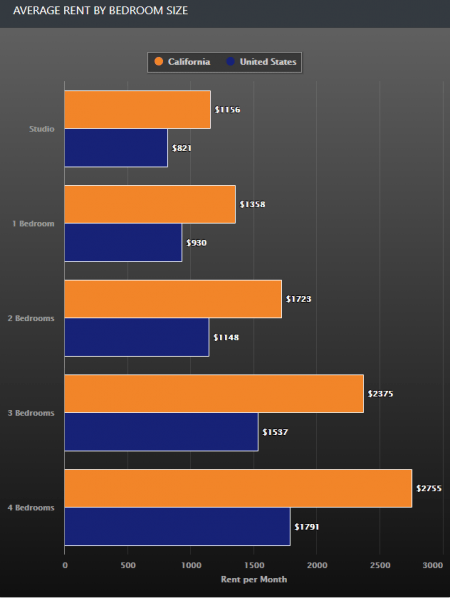

Let’s also consider the standard of living in California. The below chart only gives rental prices in California and doesn’t factor in all of the other criteria (ie, food, utilities, transportation) that go into a living standard.

Maybe under the bill, Uber workers will be able to make enough money to stop sleeping in their cars.

But let’s give Silicon Valley the benefit of the doubt. It’s highly probable that they’re simply out of touch with their worker’s needs. After all, one should never attribute to malice when simple stupidity is likely to blame.

Take, for example, the following comment from Max Rettig, the head of public policy for DoorDash, after his company joined Uber and Lyft in spending millions of dollars to lobby against the bill.

“We’re confident that California voters support a solution that pairs worker flexibility with economic security.”

California labour unions shot back:

“We will meet the gig companies’ absurd political spending with a vigorous worker-led campaign to defeat this measure to ensure working people have the basic job protections and the right to organize a union they deserve under the law,” said Art Pulaski, treasury secretary of the California Labor Federation.

A quick google search for Max Rettig and DoorDash tells us that he’s a lawyer, who went to Stanford law and works as an adjunct professor at Georgetown U. with a net worth in the six-figure range. All of this suggests that Rettig himself probably doesn’t have to worry about the standard of living in California. Therefore, it’s not unreasonable to assume that he, like many of his colleagues, is disconnected from the average gig economy worker, and probably doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

But back to Rettig’s comment for a moment—what flexibility might this be?

Uber drivers have been fighting the company in court for six years over being intentionally misclassified. Their argument is that they should be considered employees before the company has so much control over their workday, including strict rules on their vehicle conditions, what rides they can take, and which routes to use.

That doesn’t sound flexible at all. Or independent.

It almost sounds like they’re employees. But without any of the benefits or protections of employees.

But that’s the nature of the Silicon Valley con. They’ll bait you down the garden path with promises of flexibility, innovation and prosperity, and when you’re sold, they’ll switch those out with more of the same shit you’ve always dealt with, but minus all of the perks.

If there’s any takeaway from this experience it’s that we should never suspend our cynicism, and if someone’s offering you a deal that sounds too good to be true, it’s because it is.

—Joseph Morton