If bankers knew how to read drill logs – “streaming companies” wouldn’t exist. Lacking the geological expertise to accurately assess risk – big banks typically tremble at the knees when they get close to a proposed mine site.

“If we make a bad loan to a one mine company, we own the mine,” said David Scott, of CIBC Capital Markets in a recent Financial Post interview, “and we don’t want to own mines.”

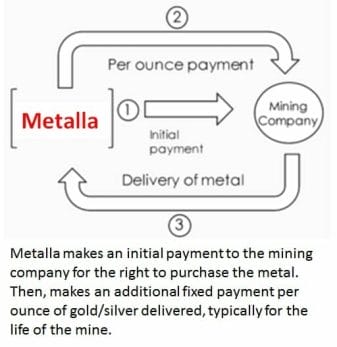

Streaming companies give cash to miners in exchange for a share of the mine’s future production.

It’s like lending someone $10,000 to build a bakery – with the baker agreeing to give you 1% of all the bread he bakes. If the bakery never opens, you lose. If the bakery produces bread for 30 years, you win. If the price of bread triples, you win. If the bakery increases production, you win.

Editor’s Note: a “royalty company” is similar but they take 1% of the cash from bakery sales – not delivery of bread.

But of course building a mine is harder than building a bakery. When I say “harder”, I mean more things can go wrong. That’s why streaming companies assemble hybrid management teams of geologists and financiers.

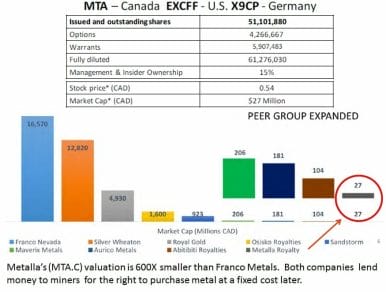

Franco-Nevada (FNV.TSX), Silver Wheaton Corp. (SLW.TSX) and Royal Gold (RGLD.NASDAQ) are three of the biggest commodity streaming companies. They have an average market cap of $8.5 billion, average revenue of $634 million and an average operating margin of 29%.

The operating margin is basically a diagnostic on the core financial engine of the company. It ignores freak expenses or windfalls.

That figure of 29% tells me that commodity streaming is a powerful way to make money. By way of comparison, General Electric (GE.NYSE), Sony (SNE.NYSE), Starbucks (SBUX.NASDAQ) and Amazon (AMZN>NASDAQ) have average operating margins of 4.9%.

Historically, big mining companies like BHP Billiton (BHP.NYSE) and Rio Tinto (RIO.NYSE) have scorned streaming and royalty deals, because they can raise money in the capital markets. Recently that has started to change.

For instance, Goldcorp (GG.NYSE) signed a royalty deal which is now owned by a microcap streaming company, Metalla Royalty & Streaming (MTA.C).

Metalla has acquired a 1% Net Smelter Royalty (NSR) on Goldcorp’s Hoyle Pond Extension properties in Timmins Ontario. The leased mining rights are east of the Hoyle Pond Gold Mine. The NSR royalty is due after the initial 500,000 ounces gold equivalent threshold is met.

Metalla has acquired a 1% Net Smelter Royalty (NSR) on Goldcorp’s Hoyle Pond Extension properties in Timmins Ontario. The leased mining rights are east of the Hoyle Pond Gold Mine. The NSR royalty is due after the initial 500,000 ounces gold equivalent threshold is met.

Goldcorp has already drilled 83,000 meters from surface and underground on the extension, spending $194 million developing the lower levels of the extension.

Metalla also owns a 1.5% NSR on the Desantis properties, owned by Osisko Mining (OSK.TSE). In fact they have a little galaxy of streaming deals.

On April 28, 2017, Metalla announced that it has signed an agreement to acquire 15% of a privately held company, Silverback for US$1.86 million. They now own a piece of Tanzanian underground mine.

The agreement states that by-product silver is purchased at 10% of the silver spot price (Example: US$1.80 per oz Ag payable in cash for US$18 silver spot price). It covers 100% of monthly silver production up to 11,250 ounces and 80% of the silver production thereafter.

A streaming company requires a high end brain trust. Metalla has recruited a team of very smart people to locate, vet and negotiate the deals. Lawrence Roulston and Mr. E.B Tucker, to name a couple, were recently added to its board.

“Mr. Roulston brings a strong technical background and streaming experience from a world class investment fund,” stated Brett Heath, President of Metalla, “Mr. Tucker brings an extensive network of mining, capital, and marketing relationships.”

Metalla is a “pure play” – they are only interested in precious metals. You won’t see Mexican copper mines in their portfolio.

You may be asking yourself: “Okay, this is a bet on the rising price of gold – why don’t I just invest in an African gold explorer?” Answer – you can and you should.

But Metalla offers investment protection and upside that explorers don’t have: it is diversified with multiple deals in different countries. Streams and royalties are paid out of top-line revenue, unaffected by rising operating costs. They also have extremely low tax rates, usually less than 8%.

If bankers could decipher an airborne survey, this investment opportunity wouldn’t exist. Admit it: it’s an attractive idea: a dozen different mines handing you gold bars right from the smelter.