Like anyone on Howe Street circa 2007, 2008, this correspondent got caught up in the Great Potash Boom.

That period would make a perfect case-study on specialty resources as story stocks, and the effects of market economies on non-renewable resources. The potash cycle has turned over once since then, and is now subject to different factors of different financial and natural environments.

In other words, it got a bit confusing for the market, so the market moved on.

So we’re going to have a look at how potash got where it is, and where it might be going from here. and what opportunities might lie going forward.

“What’s Potash? Valuable.”

For maximum effect, we’re going to start out some time in late 2007. Market types started calling each other and getting all deep about the mechanics of food and agriculture. The tune went something like:

“Most of the world’s potash is controlled by two cartels; one in North America (Potash Corp TSX:POT) and another one in Russia (Urkali + Belaruskali). They aren’t exactly in a position to compete with each other, and who says they would want to? It’s functionally a super-cartel. Potash is an agricultural necessity – a crucial fertilizer component – and it sells and ships in tonnage. There are 7 billion people in the world, and they all have to eat. Nothing grows without potash – not commercially, anyhow – and the cartels aren’t charities. This 2007 global economy is on FIRE. The developing world is industrializing, and factory jobs mean less farmland and more people to feed. Those people want better food, and they can pay for it. Nobody knows where the potash ceiling is, but the floor is a lot higher than the $450/t that it just jumped to from $200/t. Everyone’s gotta eat!”

That yarn was spun and fed to the industrial commodity traders who got in the middle of mining companies and farming companies. They owned shiploads of the stuff for seconds at a time and sold it at margins, further contributing to the runaway potash price, and getting the attention of the ‘Gucci and suspenders’ crowd on Wall Street.

Wall Street sold the yield junkies on Potash Corp and Agrium with their rock solid dividends, while they sold big-cap growth investors on Intrepid Potash and the other mid-majors being able to grow by accretion or become takeout targets themselves in a white hot commodities market. Potash seemed like a locomotive that wouldn’t stop unless people decided they would rather starve.

On the Vancouver end of the chain, companies who were in the copper business three months previous suddenly came into possession of long-forgotten potash properties. Deposits and prospects whose viability fell with the potash glut of the 70s, 80s and 90s suddenly became the cornerstone of budding mid-major potash players that the cartels would have to take out to to maintain their monopolies. The stocks traded big volumes and hedge funds elbowed each-other out of the way for private placements.

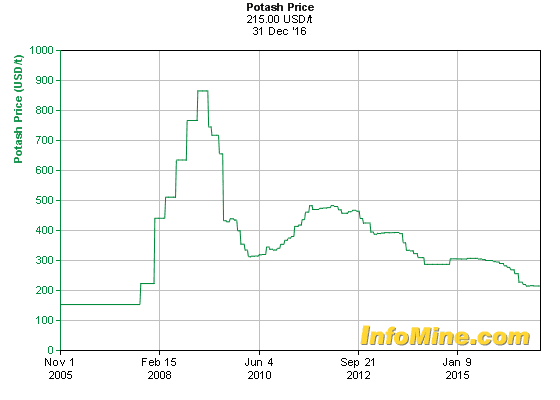

The price-per-ton of potash shot up, peaked around $850/t and leveled out around $700/t for a hot minute before sinking back to $650/t.

“Time for the plateau,” went the line, “Potash blew its top there, and it figures to go sideways for a while before it decides which way to break.”

$650/t was still plenty of room to make a potash project work on paper. The punchy potash small caps continued to trade. The broker-promoter grapevine buzz kept going with “This correction looks like a good entry point…”

Just our luck.

Then, some time around March or April of 2008, editors at cable finance networks quit having to look for bits of the market to turn into news. Steady-as-they-come Wall Street banking operation Bear Stearns had closed shop behind a collapse in the sub-prime mortgage market, and everyone was sounding pretty dumbfounded and worried. Train-wreck-level collapses led every news cycle as the great financial collapse of ’08 spread through the world like airborne herpes. Nobody wanted anything to do with any equities or corporate debt. T-bills shot to negative yields. The Dow and the S&P sunk until the major markets shut down to stop the bleeding and Wall St. cried in its scotch.

All of the exploration companies turned into wallpaper overnight, the potash ones along with them. Nobody who was still in a position to pick up a phone would pick it up a second time if you started yacking to them about a potash market.

“Potash is down to $300/t? Nobody cares. The US Government is trying to figure out how to take on more than $700B worth of bad debt without sinking, and you’re calling me about… What’s potash again? Some kind of fertilizer or something?”

But What is Potash, Actually?

To make sure we get that right, let’s go to the USGS:

Potash denotes a variety of mined and manufactured salts, all containing the element potassium in water-soluble form. Potash and phosphorus are mined products, and fixed nitrogen is produced from the atmosphere by using industrial processes. Modern agricultural practice uses these primary nutrients in large amounts plus additional nutrients, such as boron, calcium, chlorine, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, molybdenum, sulfur, and zinc, to assure plant health and proper maturation. The three major plant nutrients have no substitutes.

The world’s largest potash deposits are in Belarus, Russia and Saskatchewan. They’re leftovers from vast inland seas that formed millions of years ago and got buried for millions of years after that which is geologically cool, if you’re into that sort of thing. Those seas were the beginnings of potash cartels millicenturies in the making.

The runaway potash price that bought Lamborghinis for quick sellers in 2008 at $700 & $800/ton or so leveled out around $300/t and kept sinking. But not all Potash is created equally.

In 2015, we saw a clear break between the price of the more common Muriate of Potash (MOP) – the stuff tracked and quoted as “the” potash price – and Sulfate of Potash (SOP), an upgraded derivative of MOP.

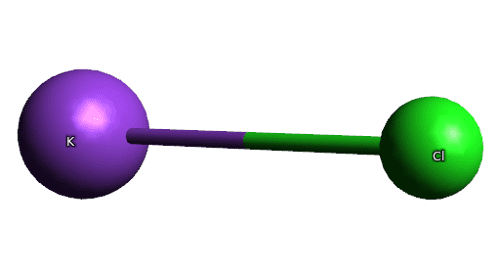

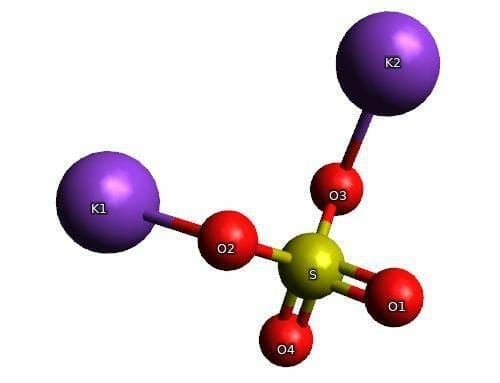

Chemically speaking, the difference is that MOP sticks the potassium that the plants need to a chloride molecule, and SOP sticks it to a sulfur and four oxygens.

Industrial agriculture is new, in geological terms. It’s even new in human terms. We only started dedicating time and energy to understanding how to get the very most out of every acre a few decades ago, but we figured it out quickly. Food is important. In the basic coarse terms that drive bull commodity markets, the nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium that plants need to grow and thrive are removed from the soil by the plants as they grow. Farms replace those elements through fertilization.

Industrial agriculture is new, in geological terms. It’s even new in human terms. We only started dedicating time and energy to understanding how to get the very most out of every acre a few decades ago, but we figured it out quickly. Food is important. In the basic coarse terms that drive bull commodity markets, the nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium that plants need to grow and thrive are removed from the soil by the plants as they grow. Farms replace those elements through fertilization.

The balance of those elements matter. The N-P-K numbers that appear on the side of fertilizer bags at the garden store are the basic shorthand for types of fertilizer. Certain plants need certain mixes of those macro-nutrients for the best results.

In actual terms, plants are biological miracles that turn sunlight and water into cells by way of photosynthesis and extraction of elements from the air and soil. They always need a mix of N P and K – especially K – but the micro-nutrients are also important components. They aren’t sold in volumes that make them industrially relevant (that’s why there’s no spot price for boron), but they matter and they add up.

Further complicating matters, variations in soil compositions and environmental conditions make the perfect growing conditions vary from place to place.

In 2015, that difference went from being worth $200/t to being worth $400/t as the prices of the two products, which previously tracked each other, diverged and kept going. Today SOP is worth more than $600/t, while MOP is still scraping the bottom at $300/t.

Commercial fertilizer doesn’t have a spot market like copper or gold. It’s price usually reflects an ongoing agreement between an operator and a consumer and figures in shipping and other costs, so prices are sourced from company disclosures and aren’t published as frequently. That’s why the potash charts always look chunky.

There is currently only one SOP producer of consequence in North America: Compass Minerals. They’re a large NYSE listed stock who produce around 350,000 tpy of SOP from an evaporation pond up in Utah, and a little more from a facility in Saskatchewan. There are a few companies looking to get in on this SOP boom, and we’ll have more on that coming up. For now, let’s look at the shape of the story, and what’s driving this market.

Ten Years Later: The Potash Story Remake of 2017

The yarn being spun today is variation of the one being spun in 2007 and 2008. This expanding economy has the developing world (and the developed world too) in a spendy mood. They want to eat well. Nuts, fruit, rich, tasty vegetables. Those are nutrient dense foods, and they need to be fertilized correctly if they’re going to yield.

The theory behind continued strength in the SOP price is that the divergence between the SOP and MOP prices had to do with the micro-nutrients that the market usually ignores. The in-demand crops are potassium thirsty, and sensitive to chlorine. The chlorine ion that comes with the potassium in Muriate of Potash causes problems in certain crops, especially the fruit and nut crops that pay right now.

Furthermore, chlorine is a salt. Its ongoing application as part of MOP fertilizer is contributing to a soil salinity problem that is threatening rapidly disappearing agricultural land.

Those things seem plausible enough, so let’s have a look and see how the claims stack up.

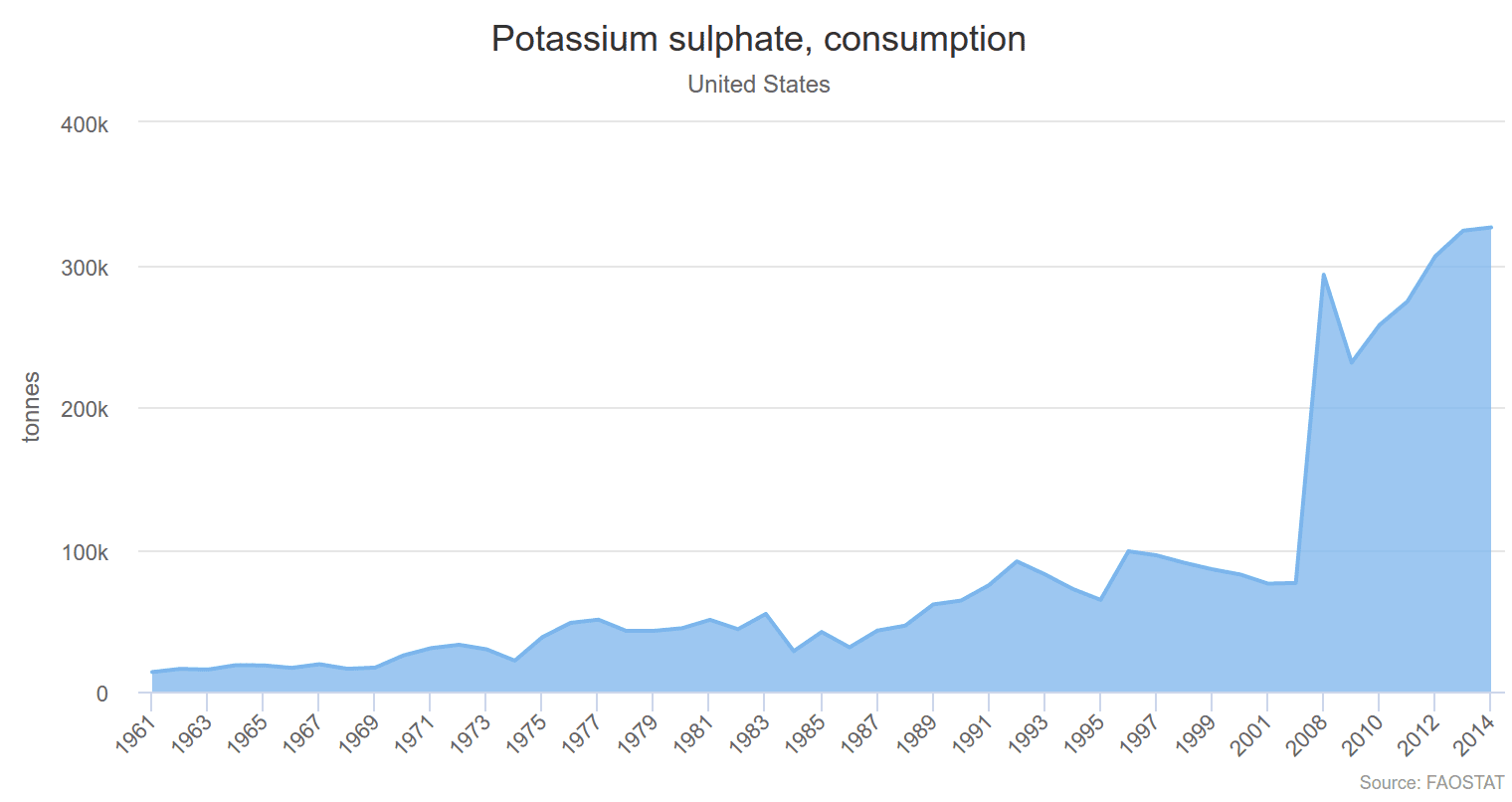

The increase in SOP price matches nicely with an increase in SOP consumption in the US (Thanks to factfish for that SOP consumption chart.) It’s charted through 2014.

The increase in SOP price matches nicely with an increase in SOP consumption in the US (Thanks to factfish for that SOP consumption chart.) It’s charted through 2014.

Compass Minerals, the only domestic producer, produced at capacity from their Utah plant: around 320,000 tons in 2016. Compass is expanding their evaporation plant and hopes to get 500,000 tpy out of it soon. Compass reports a price stabilization in 2016, but the supply trend remains intact and that’s the important part.

The consumption appears to be real, and it appears to be tracking price.

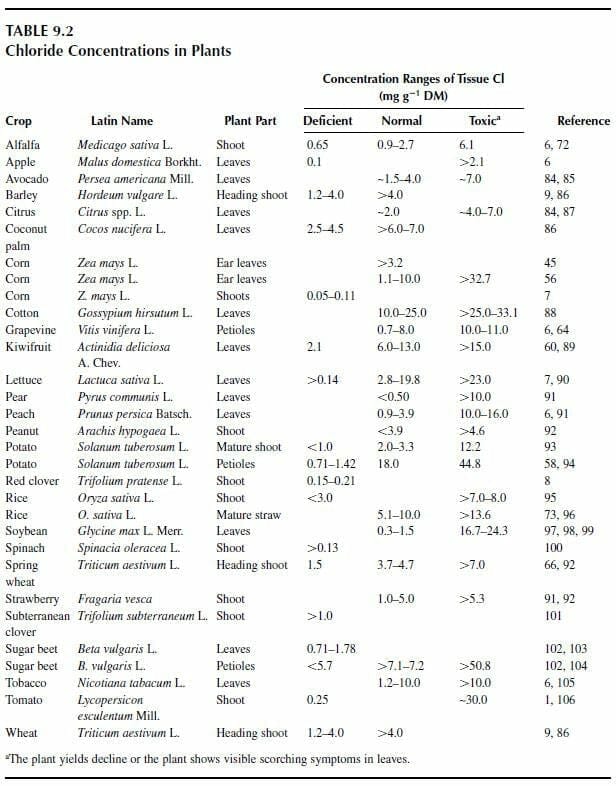

Is that trend caused by chloride having adverse effects on fruit and nut crops? The degree to which chloride effects plants varies, and so does the dispersion of these crops in commercial agriculture. Like anything, the real story follows dollars and volume. How many acres of how many crops need this stuff, and how bad to they need it? It’s a complicated problem, so let’s start by looking at the base claim: Chlorine sensitivity.

The Chlorine Angle

Chloride problems are especially notable in tobacco, where over- chlorinated plants become unsmokeable. When SOP dries up, the tobacco states treat it like a natural disaster.

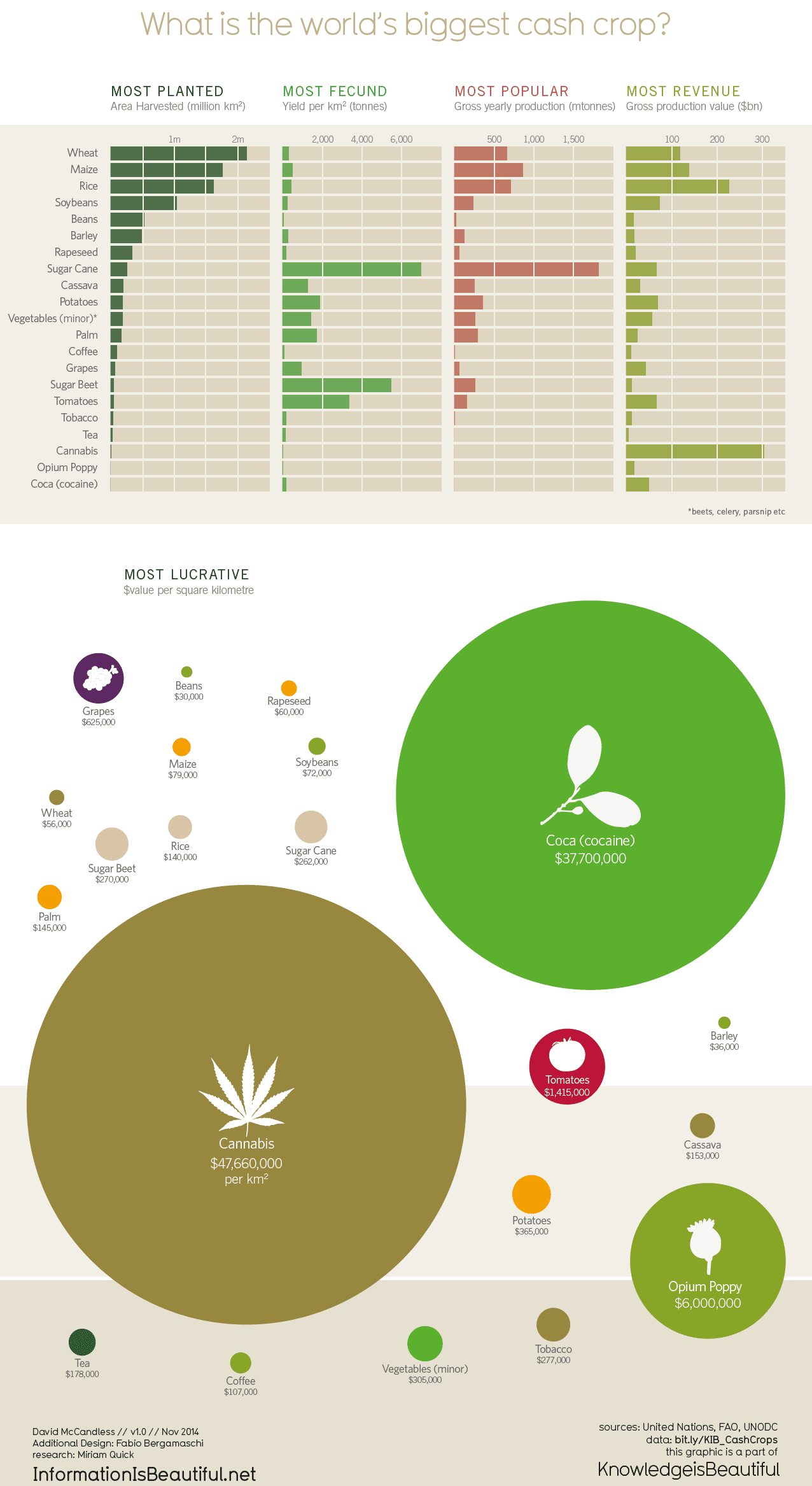

The people over at Information Is Beautiful put together this excellent graphic of the most valuable crops by square kilometer back in 2014.

Once we take away the illegal and controlled, the top three in terms of value per acre: tobacco, tomatoes and grapes, all appear on this list of crops sensitive to chlorine.

Furthermore, all three of those crops tend to be potassium-thirsty, tobacco requiring 190 lbs per acre of K, grapes requiring 125 lbs per acre of K, and tomatoes requiring a whopping 480 lbs per acre of K (Using Commercial Fertilizers, McVickar 1978).

Adding that K with chloride attached in the form of (MOP) to it, runs the risk of pushing the plant into chlorine toxicity.

Hard and Salty – Chlorine Toxicity Might Not Even Be The Point

The second, and possibly larger problem with chlorine-based potash fertilizer is the prospect of soil salinity.

Salts are formed when acids meet bases. There are all sorts of salts, and when they accumulate in soils, the soil gets hard. In places with enough drainage and water throughput, salts are flushed out of soils. In drier areas, they tend to hang around. Irrigation increases salt content, because water diverted from rivers or wells for irrigation brings salt along with it. Without proper drainage, the salt accumulates.

Irrigated farmland almost never has enough rainfall for proper drainage – that’s why it’s irrigated in the first place. Potash, by definition is potassium-containing salt.

But the potassium doesn’t tend to accumulate in soil – it gets used by the plants. Once the plants are done with the K in the Potassium Chloride that we call MOP, the chloride is left hanging around in the soil.

Eventually, whether the particular crop being grown can tolerate that chloride or not becomes beside the point. The chloride salts harden the soil, and make it difficult for water to accumulate where it needs to and nourish the crops.

It’s unclear how much soil salinity effects the land that is being used for the crops that really eat up acreage – wheat, rice, soybeans, corn.

How Does That Look In Numbers?

Today, the story that stock brokers were telling their clients in 2007 is looking more and more relevant. The US is having to use less land to feed more people, and that is putting the land under more pressure, taking more and more fertilizer.

The number to have to correctly project this trend is the total US acreage that needs to be fertilized with SOP. That’s a harder thing to figure out, so we looked at the production totals and acreage totals from the three high-dollar, chlorine-sensitive crops from the IIB graphic.

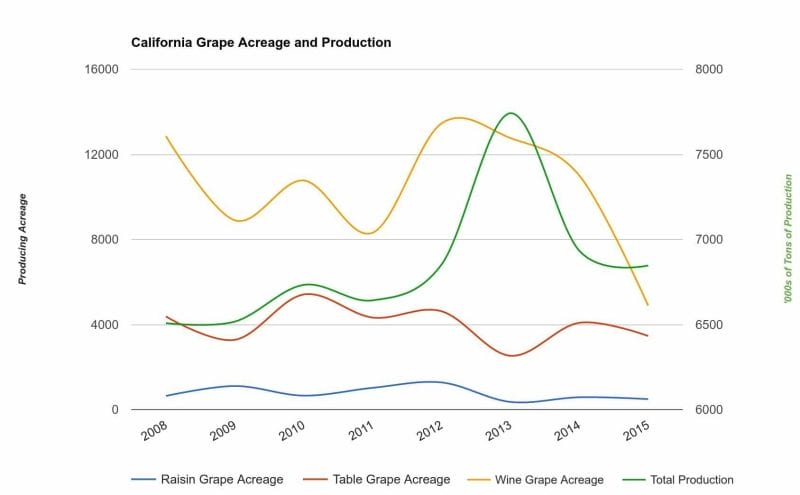

The state of California – producer of more than 90% of the US’s grapes and the victim of a terrible, extended drought, is seeing a pronounced decrease in acreage used to grow grapes, especially wine grapes. Despite declining acreage, production remains fairly steady.

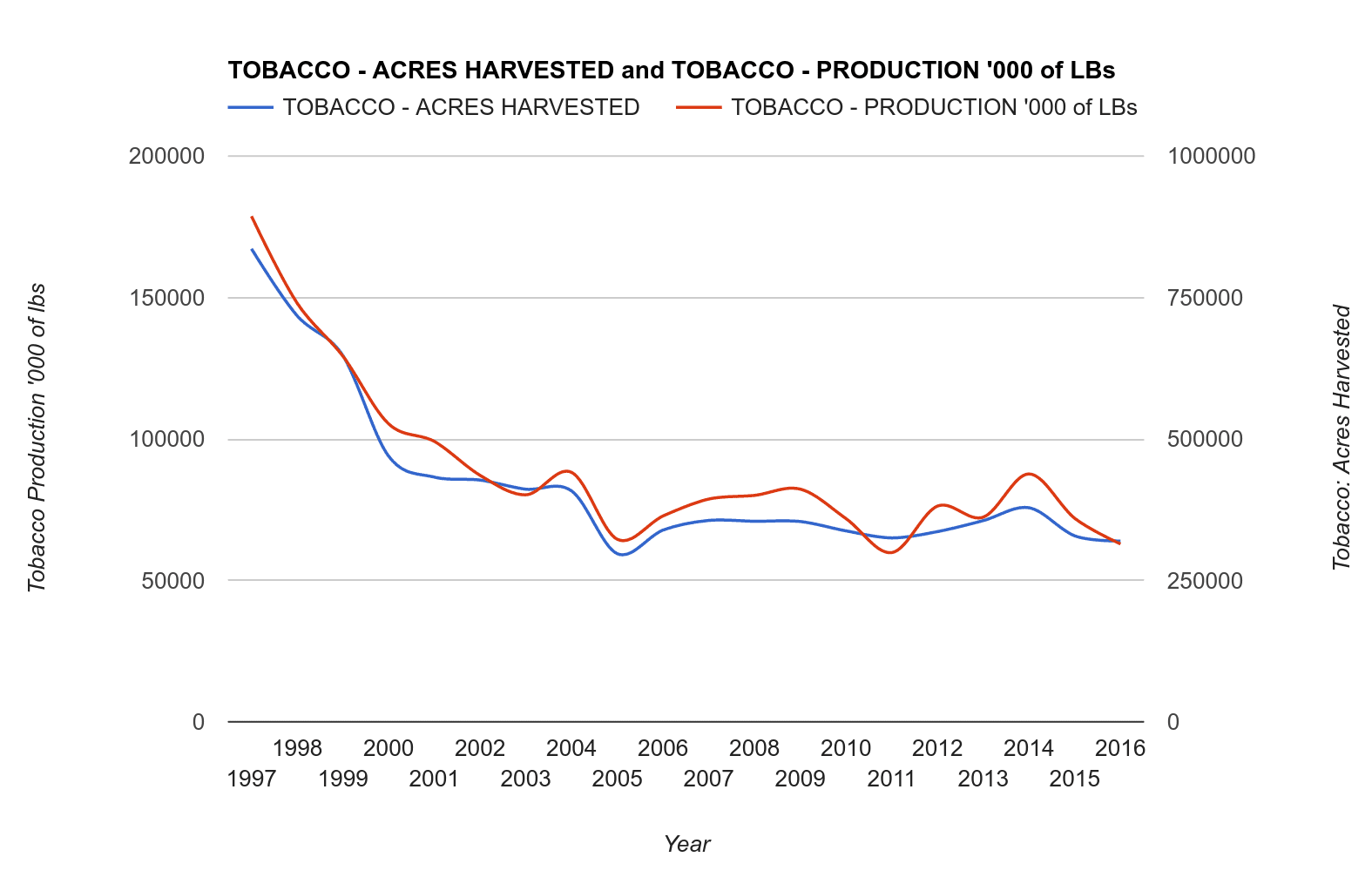

Tobacco is the steady-eddy of the high-dollar crops. A more health conscious America might have contributed to a decline in acreage and production over the years, but the trend has remained flat since 2005.

Tobacco is the steady-eddy of the high-dollar crops. A more health conscious America might have contributed to a decline in acreage and production over the years, but the trend has remained flat since 2005.

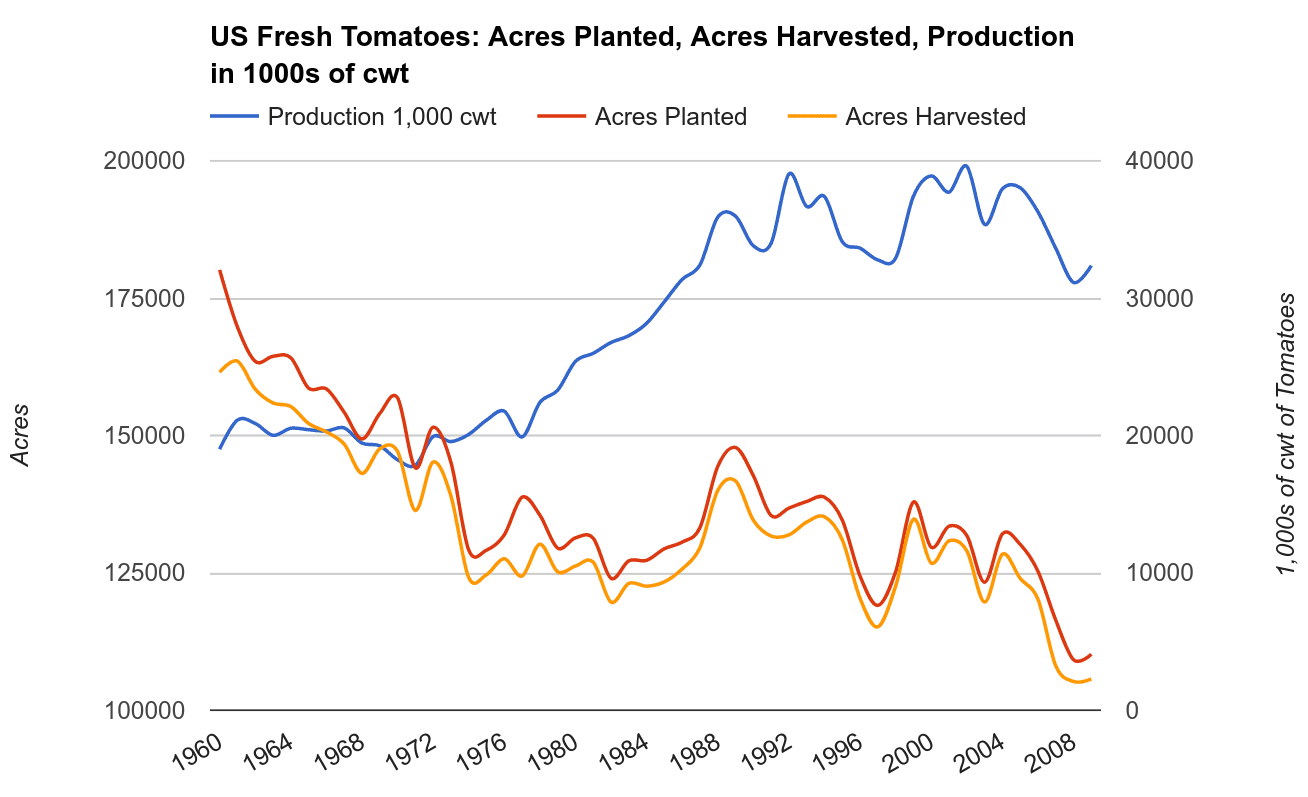

Tomatoes are the only legal crop that cracks the $1m/acre mark. Like marijuana, tomatoes have an upgrade stage. They can be sold as processed goods (canned or dried, turned into sauce), but unlike marijuana, they can be and are frequently sold to the consumer fresh. This chart tracks US Fresh Tomatoes. (note – the USDA doesn’t track tomato production as closely as they do tobacco and grapes, so there is more distance between intervals in this set, and latest data available is from 2009).

That clear divergence between the harvest and the acreage is pretty stark. While it’s dangerous to try and pin declining acreage on any one factor, the idea that it could have to do with poor soil condition matches well with the slow decline. Clearly, America’s tomato farmers have become more efficient.

The Upshot

The prospect of a warming planet has caused concern among everyone who eats – or at least it should. There is more and more rumination about the environment and crops coming out of the content-factories, which means that it’s getting attention.

When it comes to food supply, whether or not climate trends can be changed or reversed is almost beside the point: the crops that make the most financial sense are going to be grown from season to season and the farmers who grow them are going to do their best to increase yield.

While the per-ton value difference between MOP and SOP is significant in a mining and bulk-commodities context, it’s different in a farming context. The difference between delivering the 480 lbs per acre of potassium that a tomato crop needs in SOP based fertilizer instead of MOP based fertilizer is around $100/acre – a small fraction of the $1.4M in gross value that comes from its yield.

If chlorine-free fertilizer can indeed save a farmer’s acreage from hardening up and becoming useless, a few hundred bucks per acre in fertilizer costs sounds cheap.

From an investors’ perspective, the ultimate question is in that first chart: SOP consumption in the US. It shows a steep and recent upward trend. If the use of chlorine-free fertilizer continues to grow as irrigation farmers become more and more concerned with preserving their land, one can expect substantial growth in SOP demand. In an environment where there is only one US producer, running at capacity and confidently working to double that capacity, a supply side glut seems unlikely.

Which gets us to the important point. Who’s likely to emerge as a new SOP supplier?

Next on Equity Guru: am undervalued Canadian ‘big board’ potash company looking to contribute to the growing SOP market, and how they plan on doing it.

Stay tuned.