EDITOR’S NOTE: We always tell our readers to trust nobody. If we say a company is well put together, we expect to be second-guessed and for you to do your own digging, because that’s just the smart way to play. Your money is too important to just toss it in after anyone’s opinion.

But we also like to go the extra step, and actually bring you some of that extended due diligence, and so we pay Braden Maccke to kick the tar out of the companies we like, to see if they stand up to a second set of eyes.

His mandate? Be truthful. Be tough. Be fair.

Today he takes on LiCo Energy Metals.

—-

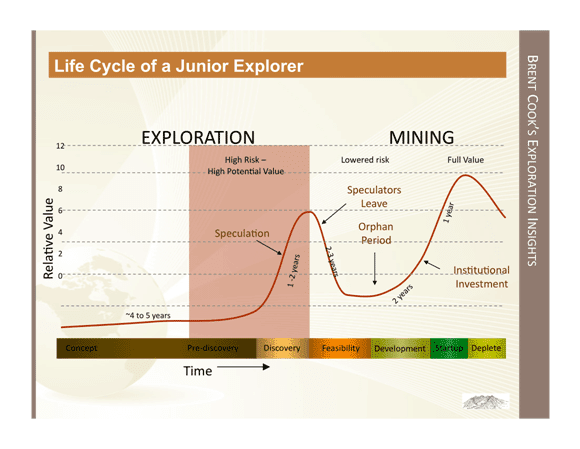

The other day on the Equity.Guru livestream channel on Twitch, I did an impromptu whiteboard version of a graph I stole from Brent Cook.

Simply put, the value curve of an exploration asset inversely tracks the risk of that asset. The de-risking effected by its operators brings the asset closer to a real live mine, producing real live metal. That relative value changes when the work of constructing a mine and operating it is at hand. By then, the project is in the hands of more risk adverse investors who deal in known quantities. They know what they have, they have a reasonable idea about how it will move forward and are happy to march it along through the process of making it into some version of a hole that spits out money. These investors are the type to bet deep favorites and satisfy themselves with modest growth as they try not to lose money.

Simply put, the value curve of an exploration asset inversely tracks the risk of that asset. The de-risking effected by its operators brings the asset closer to a real live mine, producing real live metal. That relative value changes when the work of constructing a mine and operating it is at hand. By then, the project is in the hands of more risk adverse investors who deal in known quantities. They know what they have, they have a reasonable idea about how it will move forward and are happy to march it along through the process of making it into some version of a hole that spits out money. These investors are the type to bet deep favorites and satisfy themselves with modest growth as they try not to lose money.

Those of us involved in the front end of this graphic are more interested in potential. We’re interested in companies that can take a piece of otherwise worthless ground, show that it could hold a valuable deposit, then that it probably holds a valuable mineral deposit, then that it certainly holds a valuable mineral deposit, and sell that deposit to the guy from the last paragraph who loves a sure thing for a 100x multiple.

Of course, if that were something that could be done reliably, it might not be worth doing.

The Battery Charge

In 2017, the educated world and popular zeitgeist is consumed by the prospect of humanity ceasing to cook itself without having to give up the cheap, available power that we know and love. To that end, we’ve bought in to Elon Musk’s grand dream of cars that run on batteries and solar panels that feed those batteries. The massive ‘gigafactory’ that is part of that dream is still under development in Nevada. Should it one day achieve its dream of production, that production will need to be supplied by various natural resource products.

LiCo Energy Metals (LIC.V) has assembled a portfolio of exploration assets designed to give the exploration investors on the front end of that graph exposure to the potential that a brave, new, battery-powered world may create. The anode side of the lithium ion battery cells that make up a Tesla battery pack are made of some mixture of lithium, nickel, cobalt and aluminum, for now. Nickel and aluminum being well produced and widely available, LiCo has optioned two very early stage lithium and Cobalt properties. We’ll focus today on the Cobalt asset.

A Quick Note on Cobalt

There aren’t very many stand-alone cobalt mines. It’s produced as a byproduct (usually of massive-sulphide hosted copper-nickel mines) and sourced as scrap. The largest cobalt reserves are in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which is a terrible place that doesn’t think much of labor standards or human rights.

Recently, the Cobalt price has spiked to $25/lb from $11.50/lb, as metals traders speculate that there won’t be enough supply for the growing market for lithium batteries. Since there are very few stand-alone cobalt mines, it’s a safe bet for someone who believes in a parabolic rise in lithium battery production. Byproduct and scrap are fairly consistent inputs.

The Teledyne Cobalt Project, in Cobalt, Ontario

The LiCo cobalt assets are in the re-burgeoning camp of Cobalt, ON. Ever the bridesmaid, the cobalt mined in the town named after it was mined as a byproduct of silver mines.

LiCo commissioned an NI 43-101 technical report on their newly optioned cobalt property and verified that it is the host of the hydrothermal Co-Ag mineralization that the region is known for. The property hosts the down-strike extension of a previously operated mine on an adjacent property, and previous drilling had identified mineralization on the claims that LiCo has optioned.

There is an established playbook for this type of thing:

- Conduct a prospecting program

- Identify the zone

- Drill it.

LiCo did just that, and quickly; commissioning a geophysical survey (news release Feb 8th), and announcing plans to drill (news release Feb 22nd). Companies who do what they say they’re going to do go a long way with me, so they’ve got my attention.

The recommendations section of the Teledyne 43-101 report had the surface program and follow up drilling as items 2 and 4 after the completion of a GIS database and associated 3D model, and the completion of an environmental survey to assess any legacy environmental liabilities that may exist on the property. Both of the exploration news releases mention the GIS database, so we can assume it’s underway, but there is no mention of an environmental survey. Legacy environmental liabilities can kill a project, but the degree to which a liability is the responsibility of a property’s current owner is always fuzzy. In some respects, you can’t blame LiCo for not wanting to know. In the context that there was no actual operation on the property, only exploration, I’m not going to lose any sleep over there being no survey. But let’s keep an eye on that.

The GIS database is more interesting. This is an old project full of old workings and old drill holes. There are undoubtedly maps, records and archives hanging around in the local library, at the Geological Survey of Canada, the Geological Survey of Ontario, and in dusty filing cabinets once owned by the operator of the mine next door. Compiling old historic data into a computer model is often useful for both exploration purposes and for the purposes of illustration. Zones and faces and structures become less abstract when they’re knit together in context with each other, and that’s useful for both geologists and investors.

LiCo blew off a call that they arranged with me for this write-up, and failed to set up another one, so we were unable to ascertain how far along that GIS model has come and what has gone into it.

Hydrothermal mineralization is the same kind of mineralization that one sees in gold and silver projects. It has a reputation of being erratic and tough to follow. Fortunately for LiCo, the indication is that this particular mineralization likes to hang out in the contacts between the sediments and the mafic rock. That means that the hot water carrying the silver and cobalt boiled and bubbled through the fractures that were caused as the sediments met the mafic rocks. The veins in the camp tend to occur within 200m of the contact zones. If that holds true, and the contact zones are easy to follow, explorers might have an easier time at it than, say, hydrothermal mineralization that bubbled through an already established geology in a subsequent event…. This is the type of thing that would be well addressed by a GIS model.

Dreamer Tangent

Cobalt, Ontario’s resurgence got me thinking. Hydrothermal silver-cobalt mineralization is a funny and rare thing. One hopes that the source of the mineralization that the hydrothermal fluids deposited in those veins that formed in the contact zones is still present in the local geology, and that one of these companies eventually finds it. But I got my geology degree on Howe St., so I’m liable to dream stuff like that up.

Brass Tacks and The Upshot:

LiCo Energy Metals is designed to give discovery-oriented investors an exposure to early stage properties with potential in the battery metals sector. When it comes to Cobalt, they’re in the right place to effect that kind of discovery, and they’re doing all of the right things. New discoveries are hard to come by, so I like to see companies making it easy on themselves and that’s what’s going on here. They’re in an established camp, they’re using geophysics and prospecting to establish drill targets instead of just poking away willy nilly. With a bit of luck, they might be able to build a mineralized zone that adds considerable value for those inclined to make a bet on LiCo finding the front end of Brent Cook’s value graph. The company’s investor material is generally clean and available. They appear to care about their web presence and that’s important.

The stock has a $14 million market cap, and there’s a big enough float that it’s reasonably liquid. When they generate news, they trade, and it’s prone to big swings. As I write this, LIC is 98,000 bid at $0.135, and 25,000 offered at $0.14, and has traded 118,000 shares on the day. Google makes its average volume at 256,220 shares / day.

LiCo had nearly $1.5M in their treasury last October, and had budgeted $780,000 for the full exploration program being conducted at Teledyne. The company also has exploration commitments on a lithium property in Chile, and we’ll get to that next time.

Overall, this is good value for those inclined to make a specialty metals oriented discovery bet.