90%

There are a lot of newer investors interested in psychedelics, which is great. But, there are some pretty big pitfalls to watch out for out there. It’s important to know that around 90% of investors lose money in the stock market over a 10 year period. It’s been that way since Benjamin Graham was writing stock market books in the 1940s. It’s really not that surprising either, 90% of businesses also fail.

There are a million reasons why someone would lose money in the stock market, the system is pitted against the retail investor in a lot of ways. No access to private placements (aside from exemptions) due to not being worth millions, no connections to insiders, and investment language that is purposely confusing. It’s an outdated system that originally was supposed to ‘protect’ retail investors from too much risk exposure.

In reality, it just allows the rich to get richer.

But all of that is external, arming yourself with knowledge is not, and it’s the best tool to try and be one of the 10% or so that do make money. Most of this article will pertain to longer-term value investing and not day trading or quick flips. And it is the burgeoning value investors I often see screwing this one up.

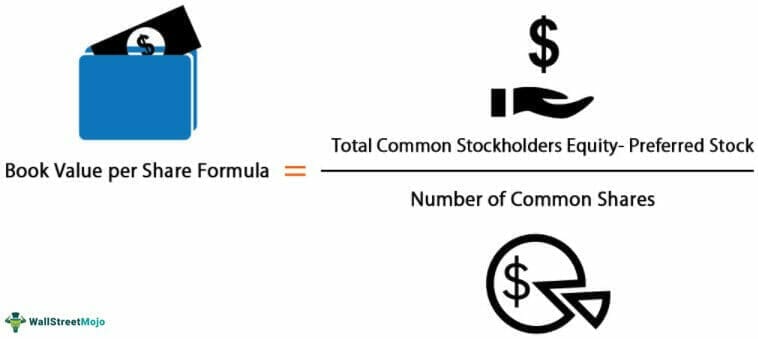

Book value per share & equity (aka based investing)

In theory, the book value of equity per share (BVPS) is the sum that shareholders would receive in the event that the firm was liquidated, all of the tangible assets were sold and all of the liabilities were paid. So the company goes under, and all that’s left is the intrinsic value. No hype, no future promises, no sizzle, no spice, just the barebones. Therefore BVPS allows us to be less influenced by future potential and more about what a company is worth today.

BVPS might not be the sexiest metric CEOs go on and boast about when they do interviews, but in terms of evaluating investment opportunities, it’s critical to understand.

To better highlight what I mean by this misunderstanding of equity, here’s an example:

Company A is priced at $0.10 per share with 300 million shares outstanding

Company B is priced at $0.50 per share with 30 million shares outstanding

(pretend this is all common shares for ease of explanation)

Without understanding equity it looks like Company A is the better value play.

I see this all the time.

‘With a share price of only $0.10 I can really load up, I could buy 5X the shares of Company B for the same price…if I had 100,000 shares of Company A that would give me more control, and more tickets to ride, and with a cheaper share price I like the upside here.’

This is a deadly mistake. I think there’s also an ego element of this well. It looks cooler to have 500,000 shares of something vs. 100,000 shares of something. So they load up on the 500,000 without even entertaining the 100,000.

It’s psychology, and even companies know this. One way in which companies control the number of available shares and how investors feel about their share price is through stock splits and reverse stock splits. Stock prices can have a psychological impact, and companies will sometimes cater to investor psychology through stock splits.

Sure, the upside on a $0.10 stock is higher than $0.70, but by that logic you may as well buy $0.00001 stocks. So why is Company B actually the far better play in terms of equity?

First, we need to understand market cap.

Marketcap or market capitalization is simply share price x shares outstanding, in other words, the market value of the company.

Company A has a market cap of $30 million (0.1 x 300,000,000)

Company B has a market cap of $15 million (0.5 x 30,000,000)

Company B, therefore, has less value than Company A as its market cap is only half that of Company A. So yes, you will ‘have more tickets’, but so does everyone else. This is what’s called dilution and it absolutely kills retail investors. And even worse, when a company does an equity raise dilution increases, and those individual shares become even less valuable.

Getting into a company who for example is young, has 300 million shares outstanding, doing considerable amounts of M&A using share-based considerations….that piece of the pie is going to shrink fast.

So for the same price, one could have either

500,000 shares of company A, which would give you a 0.00167% equity ownership stake in the company or,

100,000 shares of company B which would give you a 0.0033% equity ownership stake in the company.

Company B gives you 99.4% more equity ownership than Company A for the same cash investment.

This is how you find value.

Cost per use

This isn’t a plug for Lululemon, but I am on the path to having about 75% of my clothing wardrobe Lululemon. I used to think it was a silly company with ridiculously overpriced clothing. Why go to Lululemon and buy two things when I could redo my entire wardrobe at H&M? My Lululemon clothes that I got from doing a DJ gig at one of their marathons lasted insane amounts of travel, humidity, hikes, workouts, outdoor wear and they held up well after 5 years of taking an absolute beating. Everything I have bought from H&M has holes in it and feels like wearing a carpet compared to Lululemon’s comfort.

If you are trying to extract value from going to H&M you may actually be shooting yourself in the foot. Sure, the prices seem cheaper, but if those Lululemon yoga pants last you 10 years, is H&M really cheaper when you need to re-purchase fresh items every 1-2 years?

Lululemon also has a lifetime guarantee on all of its products without needing a receipt, meaning you can take in a pair of Lululemon shorts that are 7 years old and they will re-do the stitching or fix any damage, they will even hem your clothes in-store at any location.

So that $140 spent on yoga pants seems ridiculous on the front end, but that’s also $140 so you don’t have to buy yoga pants again. The cost per use is going to be way lower on the Lululemon pants than the H&M pants that break down every year or two.

So to bring it full circle – are you actually getting that stock for a steal at 10 cents? Or is it really just a shirt from H&M that you’re going to want to throw out after the season is over?