One of the biggest roadblocks for potential investors, the curious outsiders who toy with the notion of financial commitment to the market, is fear.

And, it is worth mentioning, this fear is not entirely unwarranted. The market is a complex and unpredictable machine comprised of innumerable moving parts, as subject to ‘auction arena’ behaviors and psychology as geopolitics and natural disasters.

But the same rationale could be applied to buying a used car. Purchasing a vehicle based on its appearance, without any knowledge of combustion engines, would be inadvisable, so why would you buy a stock you know nothing about?

Warren Buffet, a longstanding member of the financial pantheon, once said he never invested in industries he didn’t understand. The reason? A lack of knowledge creates uncertainty, and fearful people make mistakes.

Here’s what nobody ever told me about the markets: On the whole, they’ve gone up far more than they’ve gone down (but when they go down – when they correct – there is often great velocity and drama).

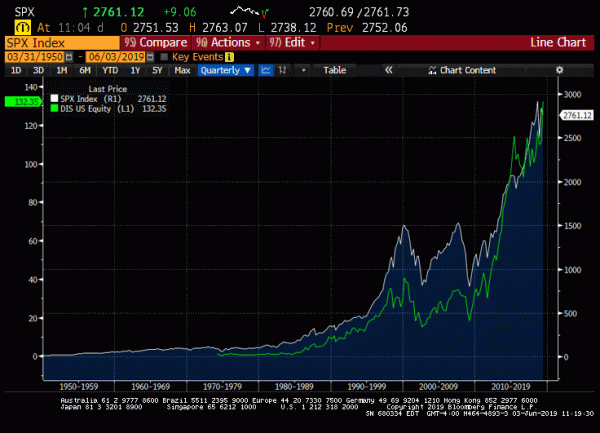

The S&P 500, which is a basket of the top 500 American companies on the stock market, is up 12,170% since 1950.

And that’s just if you follow the average market trends, commonly known as benchmarks. Picking the right stocks at the right time would deliver even greater returns.

A $1,000 investment in Disney (DIS.NYSE) at the time of its initial public offering (IPO) would have been worth over $3 million in 2018, and that’s without reinvesting dividends (a word for profits distributed to shareholders by the companies they invest in).

But success stories like these are often viewed as one-offs, flukes, whereas losses might be interpreted as the norm. Most everyone has an uncle who lost money in the stock market, and to an outside observer, its deliberate complexity and oftentimes arcane assembly can give the impression of a slot machine, with success hinging on odds stacked in the house’s favour.

This belief, that the market is unpredictable and to be avoided, is in my opinion buttressed by events like the subprime mortgage crisis, better known as the 2008 housing crisis.

The 2008 crisis was a defining moment for millennials for the negative associations it produced. From homebuyers who were offered predatory mortgages to the pensioners whose pension fund managers bought these mortgages as investments, the effects were devastating.

Leverage, a term in finance used for borrowed funds, was a root cause. Mortgages were offered to people who couldn’t afford them, and banks didn’t have the capital on-hand to bail all of these homeowners out if they defaulted (and many did).

Nobody could afford a downturn because they were overleveraged and exposed. And although millennials might not have been able to explain how, they knew Wall Street, synonymous with the market and global finance, was involved. And they were right.

The market is unpredictable, and those at the helm are either complacent or negligent, but the charts don’t lie. The S&P 500 chart included above shows a serious correction around 2008, only to rise to unprecedented heights in the late teens.

But what about the slot machine? To some, investing may be nothing more than high-stakes gambling. After all, how could so many people, investors with their livelihoods tied up in the market, not have sensed the downturn coming?

That unpredictability is known on the street as volatility, and it’s how money is made on the stock market.

Imagine a perfectly horizontal one-year stock chart, one where there is no movement in price where you buy a share at $1 and sell for $1. It’s a perfectly safe investment and a total waste of electricity.

The point is, without volatility there would be no way to double, or halve, an investment. For there to be reward, there must be risk. But the prevailing notions about the market is that it is a place where the rich become richer and the poor lose everything.

The truth is more inline with a meritocracy. Those who do their research, learn to read financial statements from companies, keep an eye on global events and have the fortitude to take a calculated risk based on due diligence, are rewarded.

Make no mistake, retail investors (a term for people like you) are up against better educated and better equipped traders at enormous firms on Wall Street. Their computers will process trades faster and their information is more up-to-date.

Trying to make a living off buying a stock at 9 a.m. for $1 and selling it for $2 an hour later is impossible for first time traders, but making educated decisions isn’t.

As Einstein said, “compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it … he who doesn’t … pays it.”

–Ethan Reyes