Equity Guru has a good track record of identifying trends just before they get hot (weed, blockchain, cobalt) – and also alerting our readers when to “take profits off the table.”

Day-to-day we’re on the ground collecting evidence (drilling down into individual companies); but at the same time we’re flying drones – taking wide-angle photographs of the landscape.

Every investor needs to understand macro money-flow. Today we’re going to explain why the Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) in Canada and the U.S. are moving in different directions – and what that means for you as an investor.

In Canada, we’ve been tracking the IPO of The Green Organic Dutchman (TGOD.V) – a weed growing monster. We got some Equity Guru readers in on an early round at $1.65. It starts trading today. At 6:50 a.m. May 2, 2018 – it’s up 3.6% to $3.73 on 3.4 million shares.

TGOD is part of a bullish Canadian trend. According to Pricewaterhouse, in 2017 $5.1 billion was generated on the Canadian markets from 38 issues. That’s up about 800% from 2016. Of that, $55.5 million was raised from 10 listings on the Venture Exchange; 95% of all Canadian IPOs were small cap companies.

In contrast, small cap IPOs in the U.S. are waning.

According to Ernst and Young’s (EY) Global IPO Report, 1,624 companies worldwide went public in 2017 – raising about $190 billion. Most of these were companies valued at over $1 billion.

Numerous financial articles have made dire pronouncements about small cap Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) in the U.S.

The Wall Street Journal claimed that “Small IPOs Are Dying – That’s Good”.

“The average listed U.S. company is far bigger than it was, and there are far fewer very small companies,” the article claimed, “The shrinking number of stocks has prompted a lot of hand-wringing among economists.”

Scott Kupor, managing partner of Andreesen Horwitz (A16Z) venture capital (VC) fund asked, “Where Has The IPO Gone?”

Kupor claims that small cap companies have been discouraged by compliance costs created by the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act. “Companies therefore wait to go public, the argument goes, until they are much larger so that they can amortize these costs over a much higher base of earnings.”

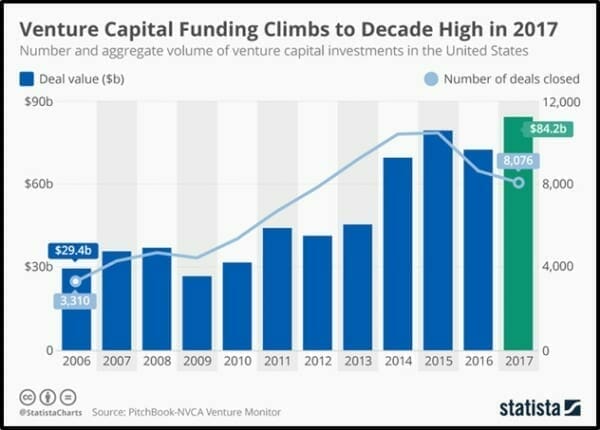

According to Pitchbook data, start-up VC financing reached a 10 year high in 2017, with $84 billion in funding – the bulk flowing into the tech sector.

“While the figures are comparable to the dot-com era,” stated PitchBook CEO John Gabber, “The VC ecosystem appears healthy…later-stage companies with strong consumer traction are commanding large rounds of financing.”

As we see from the above chart, VC investors put money into 19,000 deals, a deal number which has dropped steadily since 2015. More money pumping into fewer U.S. deals signifies a trend towards large funding rounds for more mature companies.

Underlying the trend, private companies are delaying the decision to go public. The median time for a private company to IPO in the U.S. has risen over the last 12 years, from 4.9 years to 8.3 years. When capital-hungry companies stay private longer, they often go knocking on the door of VC companies for cash infusions.

A recent New York Times article, reiterates the notion that “private capital has been so accessible that U.S. start-ups have been able to get ample funding without the headaches of an IPO.”

The “headaches” the article refers can be onerous for a young company with limited corporate resources.

According to a leading IPO law firm, “Many small companies contemplating an IPO still have start-up infrastructures, and major upgrades are necessary in order to operate like a public company.”

A 2016 Forbes article stated that, “the window for large and mid-cap company IPOs opens and closes like a heart valve, depending upon the volatility of the stock markets. But in sobering fact, in the U.S. it’s been largely sealed shut for small-cap offerings for the last 15 years.”

Regulation A+ Offerings are one way for a U.S. small cap company (maximum $50 million raise) to conduct an IPO while sidestepping some of the regulatory burdens.

In Regulation A+ IPO’s, there is no “quiet period” – the company can continue to market itself, and the volume of required paperwork is radically diminished – while the size of the raise is also constrained.

To date Regulations A+ Offerings have not attracted a lot of high quality companies. Barrons magazine research revealed that investors lost money in 50% of the Regulation A+ companies.

It’s a truism that when a company goes public, the CEO now has two jobs: 1. Manage the company 2. Manage the stock.

Given the availability of VC capital in the U.S., it’s not surprising that a lot of CEOs are choosing to delay that second job.

In Canada, we don’t have big pools of private money flowing into start-ups.

Canadian IPOs are hot, because for most companies, it’s the only practical way to raise significant amounts of capital.

The TSX.V is not for everyone. The stocks are “volatile” – which is a fancy way of saying, “They can go up – or down – very fast”.

At Equity Guru – for risk-tolerant investors – we believe that an aggressively managed portfolio of TSX.V stocks is a powerful strategy to create wealth.

We got some of our readers in on the TGOD $1.65 fund. Select Canadian IPOs should be part of that strategy.

Full Disclosure: TGOD is an Equity Guru client, and we own stock.