Last Mile Holdings (MILE.V) may have began its life as a public company on the worst possible day; literally right as North America began shutting down over COVID-19 concerns. The day Last Mile showed up, everything went to hell in a bike basket.

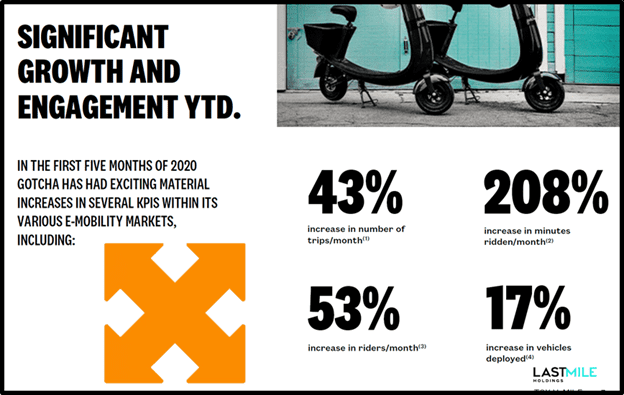

MILE owns Gotcha and Ojo, two growing micro-mobility companies providing ride-share functionality in 80 municipalities and 35 colleges across North America.

These systems are in real demand; as our cities become more and more difficult and expensive to park a car in, and as transit systems are revealed as pandemic sweatboxes, putting one’s legs to work when needing to get around is increasingly viable, and electric micro-vehicles, like scooters, trikes, mopeds, and bicycles, have the added benefit of being cheap enough to scale quickly.

That’s the good news.

The bad? Having raised money at $0.40 shortly before it went public, MILE opened on ‘let’s shut down North America day’ at $0.20, and quickly drifted to $0.10, where it’s been since.

That’s gotta hurt, especially in an industry that will require money raised every time there’s a growth opportunity.

But Last Mile hasn’t skipped a step. Management quickly understood there was little they could do about their shareprice but take it in the neck for a while, and instead of fighting the tides of investor sentiment, instead dedicated themselves to operations – and growth – of their business during the pandemic. The stock wasn’t something they could control, but their business model was.

And their business model is intriguing.

Micro-mobility ride-sharing, which is the terminology that’s been coined for e-scooters, bike-shares, mopeds and the like, is clearly an idea that has a future. Small enough to park anywhere (we’ll get to the dark side of that in a second), cheap enough to mass produce, able to be electrified and charged easily, and tied to a payment app that tracks a load of data, this business concept has everything going for it – and is being fucked up by just about everyone involved.

The bigger players, like Bird and Lime, have already spent a stadium filled with cash making sure it’s hard to compete against them by virtue of the sheer number of places and scooters they’ve slapped onto every street corner they can find. If the goal was to scale quickly and in a way that made it hard for smaller players to compete, they did that. Chances are, if you live in a North American city and venture outside once in a while, you’ve already had the indignity of tripping over a Lime or Bird scooter.

At the least you’ve seen them, you may have even rode them, hell, you might even have driven your 4×4 over one of them in anger and frustrattion after they’ve been left in your driveway once or twice too many times.

Hey @limebike – next time one of these ends up in my driveway, you’re gonna find it in a tree or at the bottom of a pool. #twithaca pic.twitter.com/8aw8dI5jHA

— Natalie Jenereski (@Natjenski) February 5, 2020

That’s by design. Lime’s business model has been simple: Drop as many scooters as you can finance all over major cities, in numbers so large that they can’t be missed.

- Asking permission first? That’s so 1990’s.

- Ensuring your vehicles are safe before putting them on the street? Nerd.

- Figuring out how to get them back to where they’re supposed to be, so the streetscape doesn’t become an obstacle course for seniors, or a scrap metal source for the homeless? OK boomer.

@limebike here’s photos of a bum destroying one of your scoots at tower 42 in Playa Del Rey California thought that you may be interested @LAPDPacific has been looking for a good reason to hook this charmer … please help the neighbors by calling @LAPDPacific pic.twitter.com/6GJtLaO7xx

— Buzz von Klüver (@EL_BVK) November 27, 2019

For the most part, the sudden rise in scooter populations in North American cities has not been invited, permitted, planned for, or welcomed by the cities in question.

Ride-hail company Uber wrote the growth-oriented playbook that scooter companies like Bird and Lime used in their early days: Launch first and ask permission later. Sometimes neither the city nor the company were ready. Lime in 2018 was forced to repeatedly pull scooters from service, first after discovering batteries in some were liable to catch fire, and then again after identifying a manufacturing defect that could cause scooter baseboards to suddenly break apart while in use.

Which is why some cities are trying to get rid of them.

Today, I notified Nashville’s seven scooter companies of my decision to end the pilot period and ban e-scooters from our streets. We have seen the public safety and accessibility costs that these devices inflict, and it is not fair to our residents for this to continue. pic.twitter.com/1IBmZRsRgF

— David Briley (@DavidBriley) June 21, 2019

e-Scooter networks suck. They may be fun to ride, but it’s also fun to dive backwards off the top rocks at Lynn Canyon, precisely because it’s incredibly dangerous. If people are stupid enough to go do that, it’s on them. But if someone installed a diving platform up there and sold tickets for access, they’d be sued to oblivion the first time Brenda from West Van took a crack to the back of her head on the way down and now needed a helper monkey to pee.

e-Scooters, at least as they come from Lime, are fun, crazy death traps.

@limebike This is what happens when stupid lime scooters are not well maintained, the handle bars of my lime scooter snapped off resulting in a broken tibia, broken fibula and 3 torn ligaments in my ankle. Thanks lime, don’t worry ill survive 14 weeks without walking pic.twitter.com/XcRsPlAiNK

— Wfskevin94 (@wfskevin94) January 15, 2020

Ouch. He’s not the only one.

Dozens of Calgarians have been injured riding shared electric scooters since they became available two weeks ago in the city. Calgary emergency rooms have seen 60 patients with e-scooter-related injuries so far. About a third of them were fractures and roughly 10 per cent were injuries to the face and head.

That’s an insane injury toll in just two weeks.

Some of that comes from design faults.

At work yesterday, I saw 5 people with @limebike e-scooter injuries in #yyc. All with the same mechanism of injury: catching their right ankle on this nut…. pic.twitter.com/2ILRZMcFwM

— Raj Bhardwaj (@RajBhardwajMD) July 26, 2019

Some of it comes from excessive levels of idiot mixed with a healthy dosage of “no F’s to give.”

Broken bones are one thing. Deaths are another.

Eric Amis, Jr. hopped on a Lime electric scooter for the last leg of his commute around midnight on May 16. The 20-year-old was headed home from his hotel job in Atlanta, Georgia. He had just pulled out of the local metro station parking lot when he was struck and killed by a Cadillac SUV. The driver later told investigators she wasn’t able to avoid him.

So, we’re all agreed micro-mobility networks are a terrible thing and should be removed immediately, right?

Well… not so much.

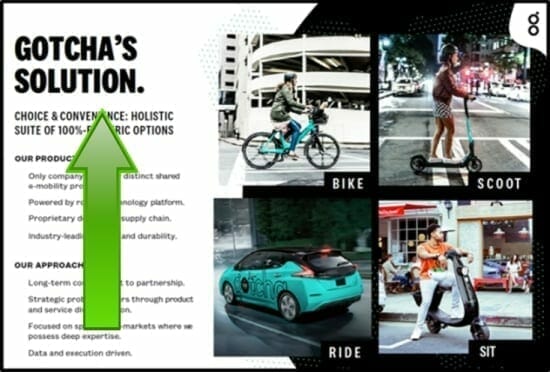

Last Mile’s companies are taking an alternate route to growth: Instead of the Uber-ispired path of least municipal resistance – basically, “HERE’S 1200 SCOOTERS, CITY X! TWEET AT US IF YOU FIND ONE IN THE LAKE. IF YOU HURT YOURSELF, RUB SOME DIRT ON IT. DON’T TELL UR PARENTS!” – Ojo and Gotcha chose the path of increased resistance – and responsibility – namely, “Here’s 30 sit down mopeds and a spot the city is comfortable with them being in, that are speed-limited to 20mph or less, and that we’ll wipe down every few days. If they break, we’ll fix them. Please be careful.”

If that sounds a little like Gotcha is the ‘Karen’ of e-scooters, they’re okay with that, because that’s what cities are looking for.

Only one electric scooter company will be allowed to operate in Raleigh, replacing Bird and Lime. City leaders approved an agreement with South Carolina-based Gotcha to deploy 500 scooters later this summer. If it meets safety, usage and “certain conduct” measures, it may be allowed to deploy 1,000 scooters.

Electric scooter companies Bird and Lime arrived last year but decided to leave Raleigh this summer after butting heads with city leaders.

Five companies — Spin, Gotcha, Bolt, Lyft and VeoRide — applied to operate in Raleigh, but city staff members only recommended Gotcha.

Holy shit.

How did Gotcha get the exclusive?

Council member Dickie Thompson thanked the staff for finding a company that knows what it means to be a “reasonable corporate citizen in Raleigh.”

“We sure didn’t hit that on the last couple of folks,” he said.

Gotcha was picked because other cities gave it a positive recommendations and it will have local staff for greater “accountability,” said Transportation Director Michael Moore.

While other e-scooter companies are fighting off vandalism to their equipment and complaints of street litter on Twitter, Gotcha’s Twitter feed seems almost… quaint by comparison.

Like this report of someone tagging graffiti on one of their maps.

Hey, Neil. The Erie Canal-themed bike racks on the corner of East Water and Montgomery streets are scratched and have a lot of graffiti on them. Who should we contact to get them spiffed up? Thanks!

— Erie Canal Museum (@ErieCanalMuseum) January 30, 2020

Restored and removed graffiti! Thank you for letting us know! pic.twitter.com/l349bGcwIb

— Gotcha (@gotchamobility) January 31, 2020

Are you kidding me?

Gotcha’s got people looking out for it, while Lime has people threatening to turn their gear into parts and playing scooter dominos.

E-Scooter Domino #escooter #lime @limebike pic.twitter.com/uzVu2dzdB2

— Julene (@JuleneMZ) January 23, 2020

How can this be?

Easy, really. Gotcha scooters, bikes, trikes, and sit-downs are more expensive than Lime’s, and it shows, because they’ve been modified for regular, ongoing, and harsh use, designed to be serviced and not thrown away, and adapted for safety. Users understand they’re not riding a broomstick nailed onto a skateboard, they’re riding a sophisticated electric vehicle.

Short, tall, our e-bike’s for all! Easily adjust the height of your seat before you ride for maximum comfort. #RideGotcha pic.twitter.com/oaj8WZgxpQ

— Gotcha (@gotchamobility) December 13, 2019

This gives the added benefit that users don’t treat them like a shopping trolley being ridden down Devil’s Canyon after polishing off half a bottle of tequila.

Think of Last Mile’s business model as the bike version of the Broken Windows Theory, where if you leave a window broken for an extended period, or a wall covered in graffiti, or trash uncollected, people in a given neighbourhood will take less care of the property nearby.

A heavier, speed-capped, safer, and more comfortable scooter, that has been well maintained and properly placed after bring permited by the city, get mor respect from users.

They’re less likely to end up in a situation like this:

Tried to jump the ramp with the lime scooter pic.twitter.com/NBQxP2suBI

— Tanner (@tbrumm_) May 12, 2020

The proof of that comes from a simple news story search involving cities that Last Mile companies moved into.

Lime offered dockless rental bicycles in Mobile [Alabama] from summer 2018 into early 2019. In a single afternoon and evening of messing around on Gotcha scooters, I saw more people riding them than I saw on Lime bikes the whole time they were here.

Let’s shift to East Lansing, Michigan, where Michigan State University told Lime to get lost, signed an exclusive deal with Gotcha, and set conditions in place that Gotcha has happily followed, such as multiple mobility options.

Gotcha scooters will remain the only e-scooters allowed on Michigan State’s campus, as the University entered a partnership with Gotcha in 2019. Gotcha scooters ridden on MSU campus must be parked in designated hubs or valid moped parking spots. Gotcha scooters must also be ridden in bike lanes or the right-hand side of the road, said the MSU Police Department.

[..] Obtaining the partnership was difficult because MSU was not just looking for a scooter provider, but rather a mobility provider said Flood. Gotcha also supplies rentable bicycles and electric tricycles.

This has been happening at an increasing rate. Last Mile subsidiaries are coming to small to mid-sized cities and saying, ‘our system won’t leave vehicles all over the place, the users won’t ride like hooligans, we’ll spend the money and take the time necessary to properly maintain the fleet, our riders won’t end up biting the curb, and you tell us what rules to follow.’

THIS IS HOW YOU GROW.

And, even in a pandemic, Gotcha in particular is growing at a clip, because the people who make decisions on mobility issues for a city will talk to their equivalent in a city that’s already gone through it, and what they usually don’t want is anything to do with a company that just decides one day to drop in and dump trucks full of scooters about.

Which might be why the big boys are starting to feel the pain.

[Lime comms guy Russell] Murphy also addressed potential rumors that claim the Lime company is in financial trouble.

“We are on a drive to profitability as a company,” Murphy said. “But we have no plans to leave East Lansing. We love East Lansing. We think it’s a great place to operate scooters.”

Bird scooters first appeared in East Lansing in 2018, but according to their website they are no longer operating in the Lansing area.

The push back against the large e-scooter companies isn’t just about city fathers wanting bureaucratic norms followed. The populations of cities where Lime and Bird drop in are not just pissed at what it does to their cityscape- they sometimes swing back.

An April 2019 report on micromobility from the National League of Cities (NLC) found that 48% of San Francisco residents already have a negative view of e-scooters.

“Many criticisms from residents included the right-of-way crowding, dangerous drivers and blocked sidewalks from operating or discarded scooters. There were also anti-scooter vigilantes who broke scooters in half, placed them in trash cans, painted them and even tossed them into bodies of water,” the NLC report said.

Venture capitalists are dummies. For every big win on an AirBnB or a Twitter, there’s a thousand swings and misses, a hundred impatient early exits, and a few inches thick of dried blood on the lobby carpet. An investing strategy of just taking $25k of every startup going and hoping one of them wins while you tell them what font their website should use is not an actual strategy, it’s firing an arrow and painting a target around it

VC’s do a lot of dumb things and claim it to be wizardry. They never want to see a down round, even though a down rounds means a cheaper buy-in. They seemingly haven’t heard of female executives or people of colour. And they insist on getting to scale immediately and losing money on every transaction to put a moat around an idea, rather than making excellence of execution, high quality end product, and responsible growth and profits their differentiators.

There are certainly places where mass execution at speed makes sense – a software technology, for instance, scales really cheaply on the back of nothing more than word of mouth, good marketing, and servers that don’t quit under the strain.

But if you wanted to corner the market on, for example, commecial real estate, and your plan is to just own all of it before a competitor can come in, and you’re a financier literally telling the CEO you’re giving billions to ‘You’re not crazy enough…”, (what’s up Softbank and WeWork) then you’re a tool, not a genius.

That thinking admittedly brought us ride-share startups like Uber and Lyft, which made early investors super wealthy and will eventually drive the taxi and limo industries out of business while also cutting their own throats. It brought us car share systems like Car2Go, which all but ceased operations in February because, when it comes down to it, if Uber is going to make it cheaper to be driven by someone than to drive yourself, why drive at all?

And it has now brought us micro-mobility ride systems, which usually involve banks of clunky one-size-fits-all bicycles with baskets on the front that make you look like the Wicked Witch of the West minus the hurricane, or the constant littering of broken, dangerous, and discarded scooters.

The Uber model of asking forgiveness rather than permission, and hoping municaplities don’t notice you’re breaking by-laws (and sometimes actual laws) before they can shut you down, doesn’t always work. If I set up a chain of unlicensed bars selling half priced beer, the hammer would fall on me hard and fast. If I set up a fleet of buses and just started collecting passengers at bus stops without being permited to do so, those buses would be at auction in a month.

Along the same thinking, Lime and Bird may just manage to get enough people using their system to not get kicked out of a good number of places they’ve set up… but at a lot of others they’ll be run out of town on a rail.

What happens when they spend a ton of money to get into a city, only to get kicked out and replaced by a company that agrees to follow the rules? In essence, just as happened with Raleigh, Lime and Bird end up losing money for a year as folks try out their system, and then get booted so Gotcha can benefit from the money those two spent on regional startup and marketing costs.

And that’s before we even get into the massive amounts Lime and Bird are spending on their hardware, which often has to be heavily maintained – or replaced – just a month after its rolled out. As Lime runs low on financing and is years from profitability, its vehicle churn means it has to either exit low performing cities entirely, leave some of its fleet unoperational and dumped by the side of the road…

.@limebike #scooter dead scooter at corner of E6th and Euclid Ave in Cleveland Ohio has been here since Monday. pic.twitter.com/gF1yp8xPmq

— Apple 2 Games (@Apple2Games) December 13, 2019

… or start taking on bad financing deals.

Such as it’s recent ‘investment by Uber’, which was in actuality a way for Uber to ditch one of its money bleeding enterprises. After cutting 13% of its workforce last month, Lime was so keen to get $85 million to keep itself afloat, that it agreed to take on a company losing $60 million per quarter.

Lime, which announced it was permanently withdrawing from Santa Monica last month, will take over Jump, a bike and scooter company previously owned by Uber that is still operating in the city.

Uber lost $2.9 billion in the first quarter as rider demand plummets amid the coronavirus pandemic and is offloading Jump to Lime to cut costs. Jump was already losing about $60 million a quarter before the pandemic.

[..] Uber will invest $85 million in Lime as part of the acquisition.

Lime’s previous valuation was $2.4 billion. This Uber ‘investment’ brought them back to just under $500 million.

Hey, what do you know? A down round!

Bird, faring no better, sliced 30% of its staff recently.

Nearly two-thirds of the @LimeBike junk clogging up Seattle’s sidewalks (a constant barriers to people with disabilities) have been found by the @CityOfSeattle to be “unrentable”. They should have never been here in the first place. #DisabilityJustice

— Joe Stormer (@PopulusEyedJoe) December 5, 2019

I had a long chat with Last Mile CEO Max Smith this week about his company, and to say it was eye opening was an understatement – precisely because everything Smith says about his company is an understatement. This cat is a no hype, all the numbers known by heart, bury the lede kind of guy. As he works through the pitch, you’re continually finding yourself saying, “Wait a second, what? How was this not on your first presentation slide?” as he casually tells you something amazing.

Like this:

Me: Do you feel like you’re well equipped to grow this company to a big exit?

Him: Well, it would be my ninth exit, so..

Me: Wut?

Or maybe this:

Me: Lime’s in 23 universities. How are you going to catch up to that?

Him: Well, we’re in 35.

Me: Wut?

Or maybe this:

Me: You’ve got 5k vehicles out there, right?

Him: Yes.

Me: Working through government permits is a slow process, how long until you can double that?

Him: We have 11k more permited and waiting for deployment right now, with 80%of that in exclusive contracts, but we’re going to make sure the rollout is responsible and the technology has a chance to be upgraded to another level before we put them out.

Me: Wut?

You know – yeah, you, reading this article -that if you were Max Smith you’d have 16k el cheapo vehicles out on the streets right now and you’d be bragging about it and raising money and driving stock jumps and NOT GIVING TWO SHITS about whether Chad in Santa Monica skins his chin because the handlebars are a bit shaky, and that’s why you’re where you are, and not running the next Max Smith exit.

I mean, just go look at the investor deck. It’s crammed with more info I can’t fit into this already stacked article, because I’m tired and it’s late and I don’t want to seem like a Gotcha homer.

IN SHORT:

Lime’s most recent Uber-led valuation was a bit under $500m, and it’s short of cash, being chased out of cities, has a trash rep all over hell’s half acre, and just took on a dumpster fire to get its hands on short term salvation cash.

Last Mile is valued as I write this at… $6 million.

That’s right: $6m.

It was $30m when it was private, $24m at its last raise, $6m right now.

Lime has 23 universities, Last Mile has 35. Lime has 195 municipalities, Last Mile has 80.

$400m versus $6m.

Where are you going to put your money?

ONE LAST THOUGHT BEFORE THE EDIBLES KICK IN: There’s going to be some of you out there, maybe many of you, that’ll assume I’ve cherry picked the worst of Lime’s social media feedback and the best of Gotcha’s. That’s a fair assumption, but would also be wrong. Just go look for yourself: Gotcha’s social is smiles and please to be safe, while Lime’s is a whole load of:

Sorry to hear about that! We will have our local team look into this.

— Lime (@limebike) November 26, 2019

Go see for yourself.

Eventually that kind of things brings a business down entirely.

— Chris Parry

FULL DISCLOSURE: Last Mile is an Equity.Guru marketing client.